“J.M.W. Turner: The Majesty of Vision” by Kyle Gallup

“J.M.W. Turner: Watercolors from Tate at the Mystic Seaport Museum”

Painting as an Aide-Memoire

Stormy seas as atmospheric notations; sheer, floating sunsets; a bright-white moonrise over a glassy body of water; imaginary, architectural views of early nineteenth-century buildings; and a pastoral River Thames on a cloudy summer day. These paintings comprise five of the ninety-two watercolors, four oil paintings, and one of Joseph Mallord William Turner’s last sketchbooks that are on view in a current exhibition, “J.M.W. Turner: Watercolors from Tate,” at the Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, Connecticut, through February 23, 2020.

The watercolors are thoughtfully selected from the Turner Bequest, which contains 30,000 works on paper left to Great Britain and housed by the Tate since 1856, five years after the artist’s death. The show is curated by Dr. David Blayney Brown,Tate’s Manton Senior Curator of Nineteenth Century British Art, and organized chronologically with informative title cards that provide important context for these visionary works within the larger arc of Turner’s long public career.

As you enter the gallery, the first dark, silvery watercolors were done when Turner (1775-1851) was in his early twenties and one, “View in the Avon Gorge,” was painted when Turner was only a precocious sixteen-year-old. In it we see a gorge and river view with an overhanging tree, rock cliffs in powdery blues, and silvery-green leafed trees, delicately painted and already masterfully detailed. These early works, along with the thousands of others on paper, filled his residence after his death. The majority of the bequest was part of Turner’s private collection, made for himself, and not intended for public viewing.

Watercolors—a fragile, fugitive medium—are seldom displayed in public. They are loaned, transported, and exhibited even less often, so it’s very special to have the works on display in the United States at all, and an opportunity to see Turner in an intimate light, not as Royal Academician and renowned artist of dramatic oil paintings, but as a far-seeing, romantic, and hard working painter.

The exhibition has many watercolors with atmospheric notes; dashes and washes of buoyant color; sight and thought as one. I can imagine that Turner used these simple landscapes for reference, and as aide-mémoire when painting other works.

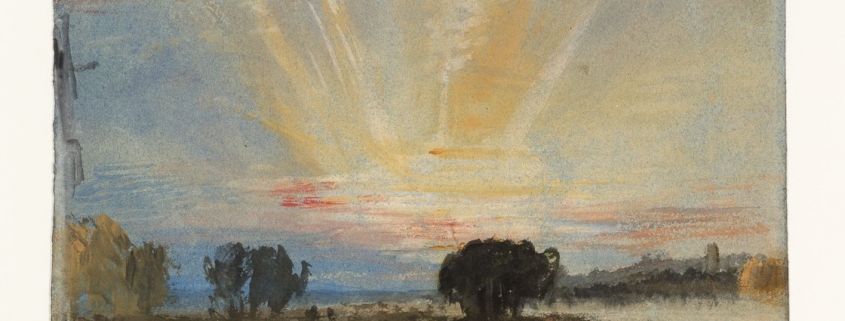

“A Wreck Possibly Related to ‘Longships Lighthouse, Land’s End’ (1834),” “Sunset Across from the Terrace of Petworth House (1827),” and “Coastal Terrain (1830-45),” give the viewer a sense of the weather conditions, movement, and hour of the day. They are Turner’s visual shorthand—pared down, yet still encompassing a larger sense of what Turner was looking at and thinking about at particular moments in time.

“A Wreck, Possibly Related to ‘Longships Lighthouse, Land’s End (1834)”. Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

Two Eureka! Moments

I experienced two eureka! moments with Turner this past year that motivated me to make the trip from Manhattan to Mystic. The first came on a trip to Margate, England, with my husband Philip Turner and British friends last March. We had come to Britain as I had been invited to a month-long artist’s residency in London. Margate is a seaside town on England’s southeast coast where Turner spent much time sketching. We were fortunate to see a number of sea-oriented Turner watercolors on display alongside the work of contemporary artist Katie Paterson in an exhibition titled, “In a Place that Only Exists in Moonlight: Katie Paterson & JMW Turner at The Turner Contemporary.”

The simplicity, delicacy, and abstractness of Turner’s pieces were surprising to see in person, yet confounding. While looking at them I had to remind myself that these were painted more than 160 years ago and were not made by a contemporary artist. As I left the exhibit and went outdoors, walking along a pier on a blustery, cloud-romping day, the Turner Contemporary’s watercolor paintings I’d just seen seemed fused together, past time collapsed in to present; the light of the day and the light of his colors were synonymous. I felt I was inside a Turner painting.

The second eureka! moment: following the excursion to Margate, while touring the National Gallery in London, I took a moment to reflect on two enormous Turner oils in the gallery. As my eyes floated over their surface, I came to an area where I could see how he had been able to transpose his watercolor sketches in to oil on these very large canvases. I understood that watercolor was an integral part of his process, in some ways the basis for his memory, and his informational archive.

Turner on an Intimate Scale

“Venice: Looking Over Across the Lagoon at Sunset” (1840) offers the remains of a bright day in oranges, purples, and yellows over a turquoise sea; as fresh today as when it was painted; the light touch, the dazzling color—this painting would have made Claude Monet jealous.

Another Venetian painting, “The Rio San Luca Alongside the Palazzo Grimani, with Church of San Luca” (1840), in gouache, graphite, and watercolor, feels like a stage set. It’s a finished sketch with fine linear buildings drawn along a canal, with windows, architectural details, and an aqueduct in the distance. Gondoliers cast afternoon shadows onto a narrow channel of water and buildings. There’s a lot of information in the small painting. The longer one looks at it, the more the work opens up.

In “Venice: An imaginary view of the Arsenale” (1840), Turner imagines sunlight on brick, the sun’s warmth lighting up the orange, yellow, and tan layers of watercolor. The solid architecture becomes fluid and shifts with the light of day. Dark gondolas, lavender shadows, and what looks like a rickety wooden bridge punctuate the painting’s deep space.

“Shields Lighthouse” (1823-26) is a nocturne in steely blues and grays. Dark clouds in black add contrast to the bright white of the glowing moon’s reflections on the water. A tiny lighthouse and the sails of boats add dimension and a quiet stillness to the scene. One can see the straight-taped edge of the paper and the wet, dry brush of Turner’s touch around the picture, which to my modern eye makes this painting feel fresh and wide open.

“The River Thames and Key Bridge, with Brentford Eyot in the Foreground and Strand-on-Green Seen Through the Arches: Low Tide” (1805) is a sublime watercolor of a cloudy, summer sky, carefully detailed; it shows a bridge with see-through viaducts and silvery green trees along the river. Tiny figures are attending to a boat, and one standing near the shore adds scale to the scene. This is a vivid moment in time captured by the artist at work. The accompanying title card states that though Turner painted most of his outdoor landscape scenes in his studio using reference sketches, this painting looks to scholars like one that Turner might have made riverside as its fleeting shadows on the bridge and foreground’s unfinished look make it seem as if he did not have enough time to complete it.

Some of my favorite Turner watercolors are interior scenes. There are two in this show. One, “The Artist and His Admirers” (1827), is a watercolor painted at Petworth House in Sussex where he spent time as a guest of the Third Earl of Egremont, a major patron of his work. The watercolor, painted on a blue ground, shows the artist at his easel in front of a small group of women. A large arched window casts light into the room. Walls of paintings, admiring ladies, and a burning fireplace are loosely sketched on the left side of the picture.

The last watercolor painting that Turner exhibited at the Royal Academy of Art, “Funeral of Sir Thomas Lawrence: A Sketch from Memory” (1830), is also on view in Mystic at the Seaport Museum. It is a large, moody work Turner made from memory after attending the funeral of Sir Thomas Lawrence, who was head of the Royal Academy, and a renowned portrait painter. The brown washes on the buildings’ façade, the built-up brush marks that create the many figures attending the funeral, and the black horse carriages add depth and a somber tone. One feels the respect the sad occasion marked for the painter.

J.M.W. Turner lived in a largely pre-photographic painting world. His approach to his work involved a constant gathering of information, and responding directly to his subjects by sketching landscape replete with color and emotion. As he grew older, his works on paper became more experimental and loosely based on elements in his familiar landscape. He kept these works private and used them to help create his monumental oil paintings. The Turner Bequest, and this exhibit from which it’s been selected, help us to see Turner as a working painter on an intimate scale, and in the privacy of his creative process. We are doubly fortunate that the scenic seaside town of Mystic, CT, was chosen as the lone North American site for this splendid exhibition. As a long time painter in watercolor this exhibit sparks my own imagination and I’m grateful I’ve had the chance to see it.

A book, Conversations with Turner: The Watercolors, edited by Nicholas R. Bell, accompanies the exhibit. Below is a gallery of Turner watercolors also on loan from the Tate for the Mystic exhibit.

Grateful acknowledgment to Dan McFadden, Director of Communications, Mystic Seaport Museum. All image credits in this essay—Tate: Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

Kyle Gallup is an American artist living in New York City. Growing up in St. Louis, Missouri, instilled in her a love of the prairie and wide-open spaces. As a painter she traverses the line between known and invented landscapes. She has developed an intuitive approach to her work that combines observation, experience, and memory. She received a BFA from Tufts University and the Boston Museum School. In 2019 she was invited to be the first international resident at Winsor & Newton Paints and Colart in London, UK, where she experimented with the historic paint company’s new line of environmentally friendly Cadmium-free watercolors. She has shown her work in the US, Canada, and Britain. Her work is in private and corporate collections, including Robert Blackburn’s print collection in the Library of Congress.

- Syon House and Kew Palace from near Isleworth (“The Swan’s Nest)”. Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

- View of Fonthill Abbey (1799-1800). Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

- “Arundel Castle, on the River Arun (1824)”. Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

- “Whitby (1824)”. Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

- “A Mountainous Coast with a Stranded Vessel, or Whale, Possibly at Penmaenmawror in North-East England (1825-38)”. Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

- “A Harpooned Whale” (1845). Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

- “Storm over the Mountains (1842-43)”. Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

- “Whalers (Boiling Blubber) Entangled in Flaw Ice, Endeavouring to Extricate Themselves (1846)”. Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

Tate

Tate

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!