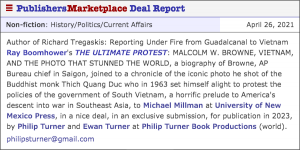

Sold: “The Ultimate Protest: Malcolm W. Browne, Vietnam, and the Photo that Stunned the World” by Ray E. Boomhower

One of the pleasures of having been an active literary agent for several years now is the satisfaction I get from selling a subsequent book by an author whose earlier book that I sold is already on the way to being published. This is the case with Ray E. Boomhower, whose biography of combat reporter, Richard Tregaskis: Reporting Under Fire From Guadalcanal to Vietnam will be published this November under the High Road Books imprint of the University of New Mexico Press. Yesterday we announced that Boomhower’s next book, The Ultimate Protest: Malcolm W. Browne, Vietnam, and the Photo that Stunned the World, has also been acquired by University of New Mexico Press. The book will detail how Browne—a most unlikely war correspondent who switched from life as a chemist to a journalist, and became the Associated Press’s bureau chief in Saigon at age 32—was the only Western reporter on June 11, 1963, to capture, with a cheap Japanese Petri brand camera, the image of Thich Quảng Đức, the Buddhist monk who immolated himself to protest the Catholic-dominated administration of South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem.

One of the pleasures of having been an active literary agent for several years now is the satisfaction I get from selling a subsequent book by an author whose earlier book that I sold is already on the way to being published. This is the case with Ray E. Boomhower, whose biography of combat reporter, Richard Tregaskis: Reporting Under Fire From Guadalcanal to Vietnam will be published this November under the High Road Books imprint of the University of New Mexico Press. Yesterday we announced that Boomhower’s next book, The Ultimate Protest: Malcolm W. Browne, Vietnam, and the Photo that Stunned the World, has also been acquired by University of New Mexico Press. The book will detail how Browne—a most unlikely war correspondent who switched from life as a chemist to a journalist, and became the Associated Press’s bureau chief in Saigon at age 32—was the only Western reporter on June 11, 1963, to capture, with a cheap Japanese Petri brand camera, the image of Thich Quảng Đức, the Buddhist monk who immolated himself to protest the Catholic-dominated administration of South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem.

Boomhower, who began publishing books long before we began working together (in fact, The Ultimate Protest will be his nineteenth title), has made a speciality of tracking the work of journalists at war, with earlier books on Ernie Pyle and Robert Sherrod, and the forthcoming book on Tregaskis, best known for publishing Guadalcanal Diary, the 1943 bestseller that was the first book in the US to emerge from the Pacific theater.

Chronicling the impact of the gruesome photo inside the Kennedy administration, from the draft manuscript:

“Jesus Christ!”

The sharp expletive uttered by President John F. Kennedy interrupted the telephone conversation he had begun early on the morning of Tuesday, June 11, 1963. The president was talking with his brother, Robert Kennedy, the Attorney General of the United States, who had called to discuss what to do if Alabama governor George Wallace made good on his promise to deny the entry of two African American students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, into the University of Alabama.

The impetus for the president’s exclamation had not been Wallace’s intransigence, but a photograph he saw splashed on the front pages of newspapers delivered to him that morning. Since May 8, 1963, when a company of Civil Guards had killed Vietnamese civilians protesting a new governmental decree outlawing the flying of the Buddhist flag on Buddah’s birthday in Hue, South Vietnam had been wracked by demonstrations. The awful image that had so startled the president showed a man—a seventy-three-year-old Buddhist monk named Thich Quảng Đức—engulfed in flames while calmly, it seemed, sitting in the lotus posture on a street in Saigon, South Vietnam.

Browne, who had been tipped off about the demonstration the evening before, was the only Western reporter on the scene to photograph the horrific event. Although the monk, as he burned, uttered no sound nor changed his position, Browne could see that his “features were contorted with agony” and could hear moans from the crowd that had gathered, as well as the ragged chanting from the approximately 300 yellow-robed monks and gray-robed Buddhist nuns who had joined the protest.

“Numb with shock I shot roll after roll of [35mm] film, focusing and adjusting exposures mechanically and unconsciously,” Browne recalled. “Trying hard not to perceive what I was witnessing I found myself thinking: ‘The sun is bright and the subject is self-illuminated, so f16 at 125th of a second should be right.’ But I couldn’t close out the smell.” The AP correspondent was almost overwhelmed by the smells of joss sticks—incense burned for religious rituals—mixed with burning gasoline and diesel fuel and the odor of burning flesh.