RIP Tyler Drumheller, CIA Operative & Iraq War Truthteller

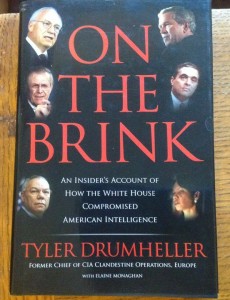

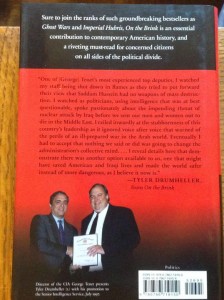

With President Obama rightly sounding a cautionary tone during his speech yesterday promoting the Iran nuclear deal—by citing the many examples of flawed judgment shown during the lead-up to the invasion of Iraq—I note with rue and sadness the death this week of Tyler Drumheller, longtime CIA operative and an Iraq War truthteller whose book, On the Brink: An Insider’s Account of How the White House Compromised American Intelligence written with Elaine Monahan, I edited and published with him (Philip Turner Books, Carroll & Graf, 2006). Tyler wrote about how he and other US intelligence officials had spotted early on that the Iraqi source Curveball was a serial fabricator whose claims about mobile biological weapons labs should not be believed. Yet Curveball’s claims remained in the inventory of malarkey from unreliable Iraqis that Bush administration officials exploited, with his bogus info being inserted into Colin Powell’s disastrous speech at the UN. As Greg Miller’s excellent Washington Post obit on Drumheller reports, Tyler was flabbergasted when he heard Powell’s speech, and bravely tangled in print and on “60 Minutes” with the CIA Director George Tenet about Curveball. It was a distinct pleasure for Tyler when I suggested to him that we use the agency photo of the two of them for the back cover photo that you see below.

With President Obama rightly sounding a cautionary tone during his speech yesterday promoting the Iran nuclear deal—by citing the many examples of flawed judgment shown during the lead-up to the invasion of Iraq—I note with rue and sadness the death this week of Tyler Drumheller, longtime CIA operative and an Iraq War truthteller whose book, On the Brink: An Insider’s Account of How the White House Compromised American Intelligence written with Elaine Monahan, I edited and published with him (Philip Turner Books, Carroll & Graf, 2006). Tyler wrote about how he and other US intelligence officials had spotted early on that the Iraqi source Curveball was a serial fabricator whose claims about mobile biological weapons labs should not be believed. Yet Curveball’s claims remained in the inventory of malarkey from unreliable Iraqis that Bush administration officials exploited, with his bogus info being inserted into Colin Powell’s disastrous speech at the UN. As Greg Miller’s excellent Washington Post obit on Drumheller reports, Tyler was flabbergasted when he heard Powell’s speech, and bravely tangled in print and on “60 Minutes” with the CIA Director George Tenet about Curveball. It was a distinct pleasure for Tyler when I suggested to him that we use the agency photo of the two of them for the back cover photo that you see below.

I worked on Tyler’s book amid an amazing, energized period of six years during which I also acquired, edited, and published Susan McDougal’s The Woman Who Wouldn’t Talk: Why I Wouldn’t Testify Against the Clintons and What I Learned in Jail (Carroll & Graf, 2001), which sort of stamped ‘paid-back’ to the Whitewater years, and Ambassador Joseph Wilson’s blockbuster book The Politics of Truth: Inside the Lies that Led to War and Betrayed My Wife’s CIA Identity, (Carroll & Graf, 2004) a story that was in the news for months, bridging Bush’s first and second terms. Following Tyler’s book—a true insider’s account that showed definitively how determined the Bushies had been to find and cultivate intelligence that would give them a pretext for invading Iraq—with journalist Murray Waas I brought out The United States v. I. Lewis Libby (Union Square Press, 2007), a compendium of public documents that featured the transcript from the trial that saw Scooter Libby, Chief of Staff to VP Cheney, prosecuted for obstructing justice in the circumstances surrounding the release of Valerie Plame Wilson’s CIA status. I’ve written more here about these books and the years when rogue prosecutors, the Bush administration, and determined adversaries were targeting authors with whom I worked.

I’m thinking of Tyler today, who less than ten years ago was devoting his reluctant retirement from the CIA to exposing how the agency had been used and abused by Bush administration officials to justify the tragic invasion of Iraq. I’m so relieved that a decade later President Obama is in charge of our foreign policy, determined to use diplomacy to make peace with adversaries.

Hiding in plain sight is confirmation in

Hiding in plain sight is confirmation in