The picture in the above tweet shows the present and former chiefs of Thames & Hudson, the publishing company that Will Balliett (r.) heads up nowadays, and which author Peter Warner–here mulling his inscription for Will’s copy of Peter’s new book–ran for many years prior. Will and I were colleagues from 2000-06, when we both worked at Avalon Publishing Group. I was glad I could attend Peter ‘s launch party last week, as he is also a publishing friend of many years. His new novel, his third, is The Mole: The Cold War Memoir of Winston Bates, published Oct 22 with Thomas Dunne Books at St. Martin’s Press. It’s already had an excellent review in Washingtonian magazine. Calling the book “crafty,” critic John Wilwol added, “Warner knows Washington intimately, and he particularly nails the way that the right social access can lead to professional success.”

Peter has established a Tumblr blog where he’s sharing the documentary underpinnings of his novel, with such artifacts as photos of CIA directors Allen Dulles and Richard Helms, a U-2 spy plane, and Senator Richard Russell, the politician on whose staff title character Winston Bates serves. Captions on the blog are cleverly written from the persona and in the voice of Bates, an expat Canadian now working for Russell, who was in real life one of the most powerful figures in the US senate. Though I haven’t begun reading it yet, this novel, like several I’ve read in recent months, especially Jayne Anne Phillips Quiet Dell, is part of a genre I’ve begun calling “documentary fiction,” with books that draw on events, artifacts, and figures from history. To show the other, more imaginative side of his enterprise, Peter Warner has created a Facebook author page with postings about the creative underpinnings of the book. This comment of his caught my eye, as the proprietor of a sister blog to The Great Gray Bridge called Honourary Canadian.

“My Personal Alternate History

In my last post I wrote about The Mole as a different take on the literary category of alternate history. But I think almost everyone has, in the back of his or her mind, an alternative life story that comes to mind on occasion: What if I had taken that job? What if I had made that investment? What if I had married that crazy person? In my case there is one alternate history that I share with almost every man of my generation: What if I had moved to Canada as a war resistor or to escape the draft during the Vietnam War era? There are also tens of thousands of American men, now Canadian citizens, who probably wonder: What if I hadn’t moved to Canada to avoid the draft? In my case, I was lucky to get a draft exemption after couple of years of anxiety. Subsequently, my publishing career took me to Canada at least twice a year for more than twenty years. I am sure having regular opportunities to imagine myself as a Canadian while in Canada played a part in the central plot of The Mole—that there might have been a Canadian “sleeper” at the heart of the American political establishment, doing his best (or worst) to undermine the so-called “American Century.” In Canada, I sometimes sensed in my friends a kind of ironic armor they had developed to accept (sometimes endure) that huge, well-intentioned, sometimes irrational, culturally inescapable, totally oblivious neighbor to the south. I hope Canadian readers will look at The Mole as a kind of delicious literary revenge.”

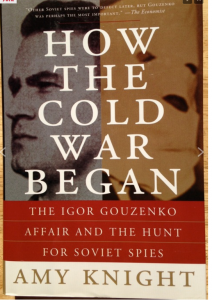

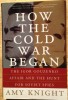

I did not have quite the same experience of the Vietnam era as Peter, since I am a bit younger than him, but my brother Joel, almost four years older than me, certainly did sweat the draft lottery along with millions of other older teenage boys in the US. One more connection that I found I have to The Mole is through a history book I published at Carroll & Graf in 2006, How the Cold War Began: The Gouzenko Affair & the Hunt for Soviet Spies, by Canadian historian Amy Knight. She chronicles the strange events involving Igor Gouzenko, a Soviet cypher clerk who in 1945, while employed at the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, walked away from his desk and defected to the West with a trove of secrets and information that indicated a Soviet spy network was then operating in North America. It became an international cause celebre, lasting for several years, with Gouzenko seeking and receiving permission to live in Canada. It was, for its day, an Edward Snowden-type event.

The intense publicity did eventually subside and about 20 years after his defection, Gouzenko actually appeared on Canadian TV, disguised by a hooded mask that had eyeholes cut out for him to see. To Americans, it looks instantly like a KKK hood, though I’m pretty sure it wasn’t seen that way in Canada in 1965. Knight chronicles this as the all-too-amazing-to-be-true-but-is story that it was. Among the odd aspects of the incident was that Gouzenko, who somehow evaded the supervision at the embassy with his pregnant wife and their two-year old son, could not at first get any Canadian authorities to accept that he was an authentic defector. They ended up walking around Canada’s capitol city for more than 40 hours, finally being believed after first futilely visiting several Canadian government offices.* Occurring even before WWII had ended, the Gouzenko incident set off a cascade of frantic maneuvering among leaders of the USA, Canada, Soviet Union, and Britain, their intelligence services, and even our FBI. The countries were all nominally still allies, but this episode displayed the ill will and suspicion that would dominate the Cold War.

It is against that historical backdrop that a character like Peter Warner’s Winston Bates operates. All these personal connections to Peter Warner and The Mole have me eager and excited to begin reading his book.

*Via this link is a fascinating video of Gouzenko’s appearance on the CBC news program “Seven Days.” The first CBC host to speak is the great broadcaster Patrick Watson, later a novelist, who in 1979 visited Undercover Books, my bookstore, for a great in-store appearance promoting his novel Alter Ego, a kind of “Memento”–type story, written many years before that entertaining film was made.

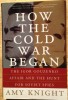

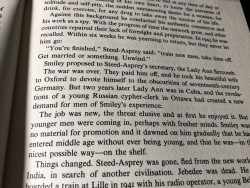

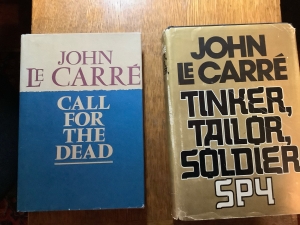

Dec 24, 2020—After putting up the post below in tribute to John Le Carré, I began reading his first novel Call for the Dead, which I had photographed copies of for the post. Right away, on page 7, I was sorta stunned to find a reference to a key historical episode, often overlooked or forgotten nowadays, that had been documented in a book I acquired and published fifteen years ago. The narrator of Le Carré’s compact, 128-page Cold War thriller explains why protagonist George Smiley, a British intelligence officer from just after the end of WWI to 1943, emerged from retirement just as WWII was ending. The reasons was “The revelations of a young Russian cypher-clerk in Ottawa [which] had had created a new demand for men of Smiley’s experience.” That cypher-clerk was Soviet defector Igor Gouzenko, whose defection author Amy Knight wrote about in her 2005 book, How the Cold War Began: The Igor Gouzenko Affair and the Hunt for Soviet Spies. Her book tells an amazing story of how Gouzenko, with his wife and children in tow, left Soviet quarters intending to defect, but struggled to find an embassy that would give him asylum. He was the first defector of the Cold War, and it was still in 1945! He became something of a media sensation in Canada, and would later appear in media there with a hood over his face to disguise his identity, as seen on he cover of the edition we brought out.

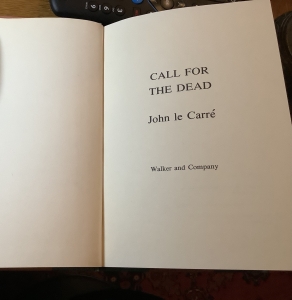

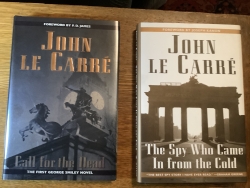

Dec 24, 2020—After putting up the post below in tribute to John Le Carré, I began reading his first novel Call for the Dead, which I had photographed copies of for the post. Right away, on page 7, I was sorta stunned to find a reference to a key historical episode, often overlooked or forgotten nowadays, that had been documented in a book I acquired and published fifteen years ago. The narrator of Le Carré’s compact, 128-page Cold War thriller explains why protagonist George Smiley, a British intelligence officer from just after the end of WWI to 1943, emerged from retirement just as WWII was ending. The reasons was “The revelations of a young Russian cypher-clerk in Ottawa [which] had had created a new demand for men of Smiley’s experience.” That cypher-clerk was Soviet defector Igor Gouzenko, whose defection author Amy Knight wrote about in her 2005 book, How the Cold War Began: The Igor Gouzenko Affair and the Hunt for Soviet Spies. Her book tells an amazing story of how Gouzenko, with his wife and children in tow, left Soviet quarters intending to defect, but struggled to find an embassy that would give him asylum. He was the first defector of the Cold War, and it was still in 1945! He became something of a media sensation in Canada, and would later appear in media there with a hood over his face to disguise his identity, as seen on he cover of the edition we brought out. In honor of the late spymaster John Le Carré, who passed this week at age 89, I was happy to take these handsome copies off a bookshelf in my library. Call for the Dead is a particularly fine copy, a first US edition of his first novel that I found in a Maine antique store in the 1990s, published here by Walker & Company in 1961. By happenstance I was an editor at Walker in 1987, where I had the mantle of publishing espionage fiction, which is when I learned that Walker was Le Carre’s first US publisher, later bringing out The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

In honor of the late spymaster John Le Carré, who passed this week at age 89, I was happy to take these handsome copies off a bookshelf in my library. Call for the Dead is a particularly fine copy, a first US edition of his first novel that I found in a Maine antique store in the 1990s, published here by Walker & Company in 1961. By happenstance I was an editor at Walker in 1987, where I had the mantle of publishing espionage fiction, which is when I learned that Walker was Le Carre’s first US publisher, later bringing out The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.