Lost American Writer Found–Jim Tully

Until recently, I had not read even one of the fourteen books by the early- to mid-twentieth-century American writer Jim Tully (1886-1947) and knew little about him. Given my personal interest in Tully’s subject matter, which included circuses, hoboes, and riding the rails, springing from his twin milieux, rural Ohio and early Hollywood, I’m surprised at myself for having been slow to pick up on him. Now, having sampled his work and discovered what an important and successful literary career he made in his life by reading the excellent new biography of him, Jim Tully: American Writer, Irish Rover, Hollywood Brawler, I’m going to do my part here to redress this widespread case of historical amnesia. I believe that now—especially in light of the Occupy Movement and the attention it’s drawing to the economic distress afflicting millions in our society—is an ideal time for Jim Tully to be rediscovered.

Until recently, I had not read even one of the fourteen books by the early- to mid-twentieth-century American writer Jim Tully (1886-1947) and knew little about him. Given my personal interest in Tully’s subject matter, which included circuses, hoboes, and riding the rails, springing from his twin milieux, rural Ohio and early Hollywood, I’m surprised at myself for having been slow to pick up on him. Now, having sampled his work and discovered what an important and successful literary career he made in his life by reading the excellent new biography of him, Jim Tully: American Writer, Irish Rover, Hollywood Brawler, I’m going to do my part here to redress this widespread case of historical amnesia. I believe that now—especially in light of the Occupy Movement and the attention it’s drawing to the economic distress afflicting millions in our society—is an ideal time for Jim Tully to be rediscovered.

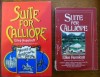

I first heard Tully’s name in 1986, when I was editing and publishing Suite for Calliope: A Novel of Music and the Circus, the first great literary novel I ever had the privilege to edit. I discovered the manuscript while serving as first reader at Scribner’s for The Maxwell Perkins First Novel Award, a fiction contest the publisher then held in honor of their storied editor who nurtured the talents of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Wolfe. Having owned and run Undercover Books from 1978-85, a Cleveland indie bookstore chain during the period that A. Scott Berg’s Maxwell Perkins: Editor of Genius was published, I was thrilled to get a job with them, my first in publishing. Working three days each week during the six-week stint, I sat in the Scribner conference room with jiffy bags and manuscripts stacked up around me like drying cord wood. My assignment was to unpack all these mailers and read between 5-50 pages of each entry, fill out a brief questionnaire, and signal a thumbs-down or -up for a possible second reading by the full-time editorial staff. Coincidentally, I recommended 70 entries, or 10%, for second readings. There was one entry I really loved, by an E.M. Hunnicutt, for which I eagerly read far more than 50 pages. My recommendation of it was more enthusiastic than for any other candidate, but it didn’t win the prize. Before finishing the job, I wrote down the author’s phone number and made a copy of the manuscript.

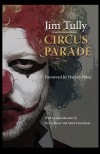

With this first stretch in the ink mines under my belt, I soon got a full-time editorial job, at Walker & Company, then a sleepy publisher of young adult non-fiction and genre fiction (Westerns, mysteries, Regency romances, etc.), published mostly for libraries. My genre was to be “men’s adventure.” Still, Walker had in its early years published books by John Le Carre and Flann O’Brien, so I was hopeful that I wouldn’t only be acquiring the male equivalent of bodice-rippers. My first week at Walker I called the initialed author and soon found myself talking with “Ellen” Hunnicutt. She told me she’d long used the initials to disguise her gender, since she had sold many stories to Boys’ Life over the years. I told her how much I had liked reading her draft manuscript, with its compelling narrator, Ada, an adolescent girl and musical prodigy who’s fled a bizarre custody battle that engulfed her family in the wake of her mother’s death. She’s sought safe harbor amid a circus troupe that’s wintering over in a quiet Florida camp and found solace in composing a requiem for her late mom on the troupe’s calliope. Ellen and I hit it off beautifully and her novel became the first original manuscript I ever acquired. Over the year that followed, Ellen and I engaged in a vigorous dialogue about her novel and its dominant theme—the creative purposes to which suffering and mourning may be put. In the course of our work together, Ellen became reinvigorated with her own book, which she’d earlier thought she’d finished. In the course of the edits and revisions, she told me about this writer, Jim Tully, and his 1927 book, Circus Parade; she praised his unsentimental portrait of the raffish big-top life, which had influenced her own interest in the circus. She explained she’d read many of Tully’s books early in her life and that his fiction and nonfiction chronicles of hobo life, circus characters, and the down-and-out of the Great Depression had still been widely read when she was a young woman.

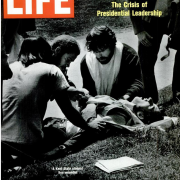

Before returning to Jim Tully, it must be said that when Suite for Calliope was published in the spring of 1987 it was given a starred review in Kirkus, Dell bought the paperback rights, and Walker sold out its first printing. The starred Kirkus happened to land on my desk on May 4, a fateful date on my perpetual calendar, the anniversary of the shootings at Kent State in 1970, the date that Undercover Books opened for business in 1978, and Ellen Hunnicutt’s birthday, which gave me the opportunity to place one of the happiest birthday calls I’d ever made to anyone, at her at her home in Big Bend, Wisconsin. And then, before the novel went to the printer, Ellen was notified she’d won the Drue Heinz Literature Prize for her short fiction; the senior judge was Nadine Gordimer. The winning collection was published by Pittsburgh University Press under the title In the Music Library. Quite a year for Ellen—perhaps she had imbibed some of Tully’s elixir for success. Working with her was a great privilege and affirmed my ardent interest in modern nomads and the circus life. For a 2004 Carroll & Graf anthology, Step Right Up: Stories of Carnivals, Sideshows, and the Circus, my editorial colleague who made the selections, Nate Knaebel, smartly chose to include “With Folded Hands Forever,” a dark passage from Circus Parade, yet as a busy editor myself I wouldn’t grasp the opportunity to read Tully’s work or properly focus on him until many years later.

I’ll add that the stirring novel of music and the circus—which another Wisconsin novelist, Mark Dintenfass, praised for “teaching the reader how to read it, with its discussions of art, psychology, and philosophy being clues to its own design”—played a role in cementing my relationship with the woman who in 1991 would become my wife, artist Kyle Gallup. When we met it was only a few years after publication of Hunnicutt’s novel. When our conversations quickly took on an an aesthetic and literary dimension, I hoped she might appreciate the book as I had. I loaned her a copy, and when she came back with a report that she really liked narrator Ada, I knew for sure we could share many things.

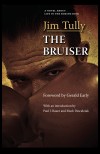

At Book Expo America (BEA) in 2010 I paused at the exhibit of Kent State University Press, from my old backyard in northeast Ohio, happy to discover that under their Black Squirrel Books imprint they were beginning to republish many of Tully’s fourteen books. I saw new editions of The Shanty Irish (with a Foreword by John Sayles), Circus Parade (Foreword by Harvey Pekar), The Bruiser (Foreword by Gerald Early), and Beggars of Life (Foreword by Paul J. Bauer and Mark Dawidziak).

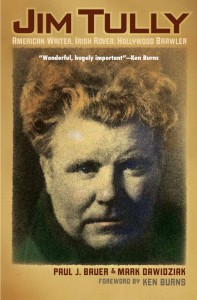

Again at BEA 2011, I saw that while continuing with their program of Tully revivals, Kent State was now bringing out a proper Tully biography, also by Paul J. Bauer and Mark Dawidziak, with a Foreword by Ken Burns. I read it last summer and found it to be a great portrait of an extremely worthy subject. Just like Max Perkins deserved and got the great book Berg, so did Tully, and while he’s not around to see his reputation shine once more, readers today can avail themselves of this terrific biography and much of his work.  Though he’s definitely been in the shadows over the decades since his death in 1947, the cultural forgetting was never complete–he had published too many bestsellers on the vagabond life and was too much of a public figure to completely drop off the map. Hailing from St. Mary’s, Ohio, his fame and relative affluence only came after a childhood which got even tougher after his mother died when he was six. His father, a veritable deadbeat dad, enrolled him at age eight in a bleak Cincinnati orphanage, which was followed by servitude in the household of a mean farmer. From fourteen, he was out on his own, living the life of a “road kid,” hopping freights, sleeping rough, learning the punishing trade of forging iron chains, boxing for small purses (a bit over 5 feet in stature and classed as a featherweight he won many matches), working as a tree surgeon (on the land of fellow Ohioan and future president, Warren G. Harding), and selling poems to newspapers for a dollar here and there. His writings all originated in observation and personal experience, doused in a hard-boiled style that arguably influenced Hemingway, Hammett, and Mailer. James M. Cain admired The Shanty Irish in a glowing review: “A yarn that soars up into the vaulted blue.” Tully became a switch-hitting bestseller, with fiction and nonfiction books appearing on the lists. He was employed as a writer by Charlie Chaplin and in demand from editors at Vanity Fair, who regularly commissioned his profiles of movie stars and Hollywood personalities, though it was well known that Tully declined to write fawning portraits of the famous. He became pals with Jimmy Cagney, John Barrymore, Lon Chaney, Boris Karloff, Tom Mix, Gene Fowler, Eric von Stroheim, W.C. Fields (the great comic and the diminutive redhead died within six months of each other), and a literary protege of H.L. Mencken, who extolled Tully to readers, emphasizing his capacity for plumbing the lower depths: “If Tully were a Russian, read in translation, all the Professors would be hymning him. He has all of Gorky’s capacity for making vivid the miseries of poor and helpless men.” Actors in film adaptations of his books included Wallace Beery and Louise Brooks. Tully’s books would also be read and admired by a young, hoboing Robert Mitchum, as I read in Lee Server’s excellent Robert Mitchum: ‘Baby, I Don’t Care.’

Though he’s definitely been in the shadows over the decades since his death in 1947, the cultural forgetting was never complete–he had published too many bestsellers on the vagabond life and was too much of a public figure to completely drop off the map. Hailing from St. Mary’s, Ohio, his fame and relative affluence only came after a childhood which got even tougher after his mother died when he was six. His father, a veritable deadbeat dad, enrolled him at age eight in a bleak Cincinnati orphanage, which was followed by servitude in the household of a mean farmer. From fourteen, he was out on his own, living the life of a “road kid,” hopping freights, sleeping rough, learning the punishing trade of forging iron chains, boxing for small purses (a bit over 5 feet in stature and classed as a featherweight he won many matches), working as a tree surgeon (on the land of fellow Ohioan and future president, Warren G. Harding), and selling poems to newspapers for a dollar here and there. His writings all originated in observation and personal experience, doused in a hard-boiled style that arguably influenced Hemingway, Hammett, and Mailer. James M. Cain admired The Shanty Irish in a glowing review: “A yarn that soars up into the vaulted blue.” Tully became a switch-hitting bestseller, with fiction and nonfiction books appearing on the lists. He was employed as a writer by Charlie Chaplin and in demand from editors at Vanity Fair, who regularly commissioned his profiles of movie stars and Hollywood personalities, though it was well known that Tully declined to write fawning portraits of the famous. He became pals with Jimmy Cagney, John Barrymore, Lon Chaney, Boris Karloff, Tom Mix, Gene Fowler, Eric von Stroheim, W.C. Fields (the great comic and the diminutive redhead died within six months of each other), and a literary protege of H.L. Mencken, who extolled Tully to readers, emphasizing his capacity for plumbing the lower depths: “If Tully were a Russian, read in translation, all the Professors would be hymning him. He has all of Gorky’s capacity for making vivid the miseries of poor and helpless men.” Actors in film adaptations of his books included Wallace Beery and Louise Brooks. Tully’s books would also be read and admired by a young, hoboing Robert Mitchum, as I read in Lee Server’s excellent Robert Mitchum: ‘Baby, I Don’t Care.’

Biographers Bauer and Dawidziak steep the reader in Tully’s lifelong struggle to make himself into a significant person; glimpsing his continual act of self-creation is what I found thrilling about this book. The authors chronicle how even in relatively prosperous years, he continued striving to create himself and forge his work. Family agonies—his son Alton served several jail terms for brutal assaults on women—sapped Tully’s energies and darkened many of his latter days. Sadly, he lived along enough to see his reputation and book sales decline, leaving him to ponder what kind of country no longer cared to read about the travails of its have-nots, even while America roared ahead into the second half of the century. I felt Tully’s sorrow as his reputation ebbed and editors no longer kept him in demand for assignments.

Speaking of fiction genres, as I did earlier, I also want to remark on the sturdy nonfiction genre of biography. For me, I often find it the inexhaustible medium for chronicling the stories as a reader and editor I most yearn to hear. What’s great about the Tully bio—and other books like it that achieve this deep level of discourse with their subject’s life—is that the reader has a chance to assemble, in ways the biographer shows a reader how to do—the ways a literary career is lived and aspired toward, and achieved. The successful biography spans the decades and folds of a life, making the living subject comprehensible and one whom we understand. That’s what happened for me with Jim Tully: American Writer, Irish Rover, Hollywood Brawler, and why this book will be on my best list for 2011.

Reward this purposeful publishing. I urge you to get a copy of this important American biography and look at Tully’s books. They gave me some of my best weeks of reading this year and are all well worth your time. Until you find a copy, you can listen to the authors speak about Tully and their book in this radio interview or read about Tully and the biography in this excellent profile by Joanna Connors from the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

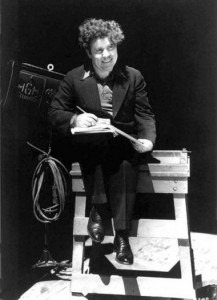

Jim Tully, on the MGM lot, (Photo courtesy of the family of Trilby J. Tully Beamon, Jim Tully Papers, Collection 250, Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA.)

Agree with you on the Tully bio – a great read, a “fully packed suitcase,” as author Paul Bauer put it. Also read it over the summer and am glad to be producing a documentary based on the book. Tully lives again!

Hi Mark,

I’m glad you enjoyed my blog essay on Jim Tully. I look forward to seeing your film. Please keep me posted as to its progress.

Best, Philip

I loved Beggars of Life and I’m enjoying Circus Parade now. A film based on Tully’s life is a great idea. I’ll watch for it!

Dan