Comics and New York City–A Beautiful Friendship

Last weekend I was privileged to attend a great event celebrating the comic arts, graphic novels, and New York City for PW Comics World, the online comics home of Publishers Weekly. The event was called Comic NY-A Symposium and my article, “Comics, New York City And History at Columbia’s Low Library,” has now been published at the PW website. If you love the comic arts and graphic novels, enjoyed watching Paul Giamatti play Harvey Pekar in “American Splendor,” or ever chuckled over MAD magazine, I invite you to read my piece at the PW site or here on my blog. FYI–the rendition below is illustrated with more than 60 photos of mine that do not appear on the PW site, which has other, excellent pictures.

—

Comics, New York City And History At Columbia’s Low Library

by Philip Turner, Mar 29, 2012

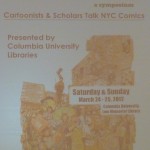

Are the creators of comics and graphic works storyteller-artists inspired by the drive to imagine the urban landscape? Or are they journalists, motivated by an impulse to document the cities where they live? As considered by a bevy of comic talent at Columbia University, the answer is they are both—imaginative artists and chroniclers reimagining and reflecting their worlds—and more. The scene for these dynamic discussions was Columbia University’s Low Library where “Comic New York-A Symposium” was held March 24-25. With thirty panelists participating in six panels, plus a keynote discussion with acclaimed X-men writer and collector Chris Claremont, more than 250 comics fans were treated to in-depth conversations about how the comic arts have been influenced by New York City and how the metropolis has absorbed the influence of the comics. Claremont was honored for donating his archive to Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

The opening panel, “New York, Real and Imagined,” began with Kent Worcester, co-editor of A Comic Studies Reader, sharing five comics images that showcased New York’s tremendous verticality; in “Gasoline Alley,” where Skeezix and Walt ride on a magic carpet high above the city, and in Superman, when the Man of Steel dangles a villain over a yawning chasm between skyscrapers. Along with the verticality the city has lent to comics, Worcester also asked his audience to consider Manhattan’s street grid, a visual analog to the panel format of comic books. Molly Crapabble, illustrator, cartoonist, denizen of New York’s downtown art scene, conceded she’s an outsider to the comics world and said that she makes frequent reference to Thomas Nast and Heironymous Bosch for the crowded scenes of ribaldry she draws. Asked about New York’s underground life, she observed that the subway is “the hair shirt” of the city, contrasted with “the sparkly, silver Babylon” above ground. John Romita, Sr., who drew Spider Man with Stan Lee, said he made New York a veritable “co-star” with the web-spinner, while his son, John Jr., aka JRJR, who drew Daredevil, spoke of the dark and “moody” look he deliberately brought to the series. TV writer and autobiographical comics artist Ariel Schrag told an improbably hilarious story about a brawl at a gay prom she attended at Columbia, events she chronicles in her coming-of-age graphic memoirs.

In the panel “Political New York,” literary agent, underground cartoonist, author and legendary comics publishing figure Denis Kitchen said that interviewing Harvey Kurtzman for the book he wrote on the founder of MAD, Kurtzman told him he’d wanted the magazine to be “a machine-gun attack on American culture,” and a “subversive” force combating “phoniness.” Sabrina Jones, graphic biographer of dancer Isadora Duncan and urban planning hero Jane Jacobs, had a dialogue with moderator David Hadju about how comics are an accessible and democratic medium that is suited well to political expression. Peter Kuper, comics artists, illustrator and co-founder of the seminal journal World War 3 Illustrated, to which Jones and many others contributed, recalled that his magazine used to be sold at head shops, though this means of “self-distribution” suffered when the alternative establishments were shuttered in periodic crackdowns. Before showing his own biting cartoons, John Carey unveiled a slideshow of images that in condensed fashion anatomized modern editorial cartooning—from Jules Feiffer’s acerbic anti-Nixon tilts to David Suter’s op-art created under Jerelle Kraus’s inspired direction at the New York Times Op-Ed page to Edward Sorel’s lacerating and always visible lines.

The underground comics scene was considered in “Alternative New York,” a panel moderated by Gene Kannenberg, Jr., author of 500 Essential Graphic Novels, who asked Bill Griffith, creator of “Zippy the Pinhead,” for his definition of “alternative” comics. Griffith, who worked alongside R. Crumb in the sixties, recalled the 1973 Supreme Court decision that criminalized dealers who sold comics, putting his work outside the mainstream. R. Sikoryak, author of Masterpiece Comics, observed that in music an alternative band one year may become a pop darling the next, and that much the same can occur in comics.

“Periodical New York” got off to a raucous start with Irwin Hasen, who drew the original Green Lantern. Now in his nineties, Hasen announced he had always wanted to be an “entertainer” and proceeded to nearly steal the show from moderator Eddy Portnoy and his fellow panelists by careening in off-topic directions with funny laugh lines. But Portnoy maintained course and steered Hasen back to discuss his experience creating “Dondi,” the strip featuring an Italian immigrant boy new to the city that appeared in many newspapers. Ben Katchor, creator of “Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer,” which ran in the New York Press for many years, rebutted the idea that comic renditions of urban life such as Metropolis or Gotham are necessarily stand-ins for New York. More than some of his fellow speakers, Katchor insisted on the primacy of “invention,” recounting for instance that a newspaper he created for his comic world, The Evening Combinator, “reported the dream life of the city.” Cartoonists Emily Flake and Lauren Weinstein described searching for a fictional truth, a truth that goes beyond the facts and gets to the heart of a city. Both women embraced what one called “the delightful improbability of urban life.”

In a discussion of New York as a breeding ground for comics, the venerable MAD cartoonist Al Jaffe recalled getting his start in the studio of the legendary comic strip and comic book innovator Will Eisner, where he created the character “Inferior Man,” a kind of super-antihero. Jaffe called Eisner “a brilliant artist, brilliant writer.” Moderator Danny Fingeroth asked Dean Haspiel—the prolific artist who’s drawn Harvey Pekar’s The Quitter, Cuba: My Revolution with Cuban writer/painter Inverna Lockpezas and many other works—if he could identify why New York high schools have produced so many comic artists. Dean was stumped and, drawing a laugh from the audience, he conceded that when he studied art at LaGuardia High School, he didn’t even learn to draw perspective. Tracy White, author of the graphic novel, How I Made it to Eighteen, kept the laughs coming when she remembered that on a bus she took regularly as a teenager she noticed a man who was evidently getting “hair plugs,” because each day he appeared slightly more hirsute than the day before. Thus, she learned to be a perennial observer. Miss Lasko-Gross, author and illustrator of A Mess of Everything, cited her own upbringing in suburban Massachusetts, which made finding a foothold in New York all the more essential in her progress as an artist.

A panel examining comics in the academy wrapped up the two days with a lively discussion of how the field is slowly becoming an integral part of the wider scholarly world. N.C. Christopher Couch, of the School of Visual Arts, suggested that a canon of essential graphic novels and comics should be promulgated so that a reader or a student approaching the field will know what they must read. Paul Levitz, a longtime president and publisher of DC Comics, now teaching a course at Columbia, urged scholars to get busy interviewing the aging veterans of the early decades of comics, lest they pass away before their memories are preserved. Jonathan W. Gray, of John Jay College at CUNY, noted the growth of cross-disciplinary studies with many collaborations occurring among scholars in art history and various literary fields.

Comic New York was a richly rewarding event for artists, writers, and comics fans, who availed themselves of the well-stocked book table, buying many copies of graphic novels and books of comic art that were autographed by panelists between sessions. To Columbia’s credit, it should also be noted the symposium was entirely free of admission charges. Additionally, videos of the panels and the keynote will be up on the site within a week or two.

Comic New York was mounted not only to bring together creators, scholars, and fans but also to celebrate the donation by keynoter Chris Claremont—best known for his work on “The Uncanny X-Men” and “Wolverine”—of his personal archive to Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Karen Green, graphic novels librarian at Columbia and organizer of Comic New York, is hopeful that Claremont’s donation represents the “beginning of wider acquisitions in the papers of comics writers and artists in the New York City area.” As comics become ever more important at Columbia, Green expects to be holding other events in the future.

Philip Turner is a lifelong comics reader, longtime editor and publisher. As a retail bookseller in the 1980s, Turner was pleased to have graphic novel pioneer Harvey Pekar as a regular customer in his Cleveland bookstore. His previous story for PW Comics World was “PEN World Voices: Getting Real With Superheroes.” Turner blogs at The Great Gray Bridge.

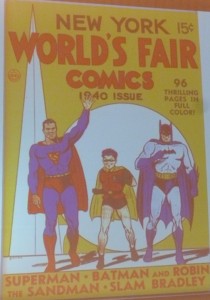

- World’s Fair with Superheroes

- Comic NY poster

- Karen Green, graphic novels librarian, Columbia University

- Ariel Schrag, Molly Crabapple, JRJR (photo by Kyle Gallup)

- Peter Kuper, John Carey, Sabrina Jones, Denis Kitchen

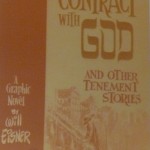

- Will Eisner’s Contract With God

- World War 3

- World War 3

- WW 3 covers

- Edward Sorel

- Nixon and Ford by Edward Sorel

- Op-Art, David Suter

- Grover held hostage, John Carey (Greater Media Newspapers)

- Hammer & sickle as a human face, David Suter

- Donald Trump by John Carey (Greater Media Newspapers)

- If Stravinsky had Lived in Suburbia, John Carey (Greater Media Newspapers)

- Jane Jacobs by Sabrina Jones

- Sabrina Jones panel

- Gene Kannenberg, Jr.

- Bill Griffith

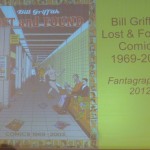

- Lost & Found Comics, Bill Griffith

- Zippy the Pinhead by Bill Griffith

- Zippy

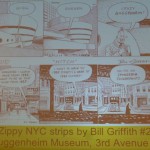

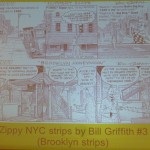

- Times Square strips, Bill Griffith

- East Village Other scene, Bill Griffith

- Big Boy, Bill Griffith

- R Sikoryak, Bill Griffith

- Masterpiece Comics, R Sikoryak

- Popysseus, R Sikoryak

- Bill Griffith, Charles Brownstein, director Comic Book Legal Defense Fund

- Comic Book Legal Defense Fund logo

- Julia Wertz, author of Drinking at the Movies

- Drinking at the Movies cover

- Drinking at the Movies interior

- Eddy Portnoy

- Irwin Hasen’s Dondi

- Irwin Hasen, Emily Flake

- Boxer by Irwin Hasen

- Ben Katchor

- Hall of Pain, Ben Katchor

- Regularity Cafeteria, Ben Katchor

- Out of Pocket Clothing, Ben Katchor

- Lauren Weinstein

- Self Visualization Activity, Lauren Weinstein

- Work of Lauren Weinstein

- Danny Fingeroth

- Al Jaffe

- Al Jaffe’s Inferior Man

- MAD cover

- MAD men

- Al Jaffe created MAD’s monthly fold-in

- Miss Lasko-Gross, Dean Haspiel

- Dean Haspiel

- Awful George, Dean Haspiel

- Street Code, Dean Haspiel

- Calvin Reid, Publishers Weekly

- Jonathan W. Gray, CUNY

- East Village Other, Art Spiegelman

- East Village Other, R. Crumb

- Jive Comics, R. Crumb

Even more documentation! Great!