Treasuring Early Natural History Books

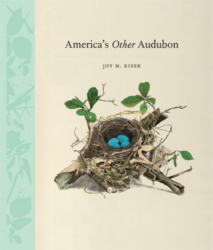

Always happy to see a story involving my old hometown Cleveland’s book culture–Judith Rosen of Publishers Weekly reports that an 1886 book of natural history and ornithology, Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio, a copy of which was discovered in 1995 in the library of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, is now being republished by Princeton Architectural Press. PAP’s catalog listing for the book shows that the new edition has been retitled America’s Other Audubon by Joy Kiser, the librarian who found one of twenty-five remaining copies of the rare book.

Always happy to see a story involving my old hometown Cleveland’s book culture–Judith Rosen of Publishers Weekly reports that an 1886 book of natural history and ornithology, Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio, a copy of which was discovered in 1995 in the library of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, is now being republished by Princeton Architectural Press. PAP’s catalog listing for the book shows that the new edition has been retitled America’s Other Audubon by Joy Kiser, the librarian who found one of twenty-five remaining copies of the rare book.

The author, Genevieve Jones, an amateur naturalist of her day, was inspired to create the book after seeing Audubon’s Birds of America paintings at the World’s Fair of 1876. She created sixty-eight original lithographs in making her book, which contemporaries described as “the most beautiful book ever produced in America.” Sadly, Jones died before it was finished and her family labored seven years to see to its completion, then underwriting printing and selling it by subscription. Only 90 copies were produced, and among the subscribers were Theodore Roosevelt and President Rutherford Hayes.

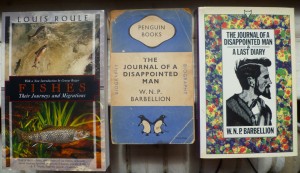

I love old natural history books, such as The Journal of A Disappointed Man by W.N.P. Barbellion, to which H.G. Wells contributed an Introduction upon its publication in 1919–a few months before the author died of multiple sclerosis at age thirty. Two sample entries from Barbellion’s youth, January 3, 1903: “Am writing an essay on the life-history of insects and have abandoned the idea of writing 0n ‘How Cats Spend their Time.'” and March 18, “Our Goldfinch roosts at 5:30. Joe’s kitten is a very small one. ‘Magpie’ is its name.” I have an old Penguin copy of the book and a reprint published in 1989. Then there’s Fishes: Their Journeys and Migrations by Louis Roule, originally published in 1933, which I republished as a Kodansha Globe title in 1996, with a new Introduction by George Reiger of Field & Stream magazine. A reviewer of the original edition wrote, “Will please the nature student, the Izaak Walton enthusiast, or the reader who delights in believe-it-or-nots.” Living in an age of diminishing biological diversity with an accelerating pace of extinction, it is important to be aware of species and varieties that used to be common and are no more, or increasingly scarce, and I treasure these books for aiding that effort, decades after they were first published. That’s kind of miraculous.