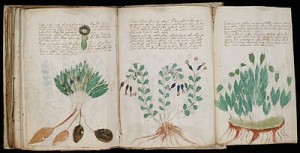

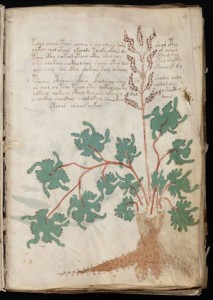

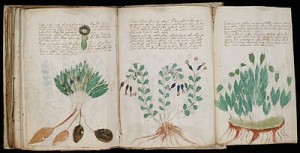

March 3, 2014 Update: I first wrote about the Voynich Manuscript on this blog more than two years ago. As was the case then, decipherment of the mysterious codex still continues to elude linguists and scholars, though two recent posts in the Moby Lives blog (one and two) indicate they may be getting closer to at least getting a geographical fix on the plants that are included in the extravagantly illustrated work. Julia Fleischarker reports that “Dr. Arthur Tucker of Delaware State University…writes that taking the botanical illustrations as a starting point enabled them to help place the manuscript geographically,” which he now believes to have been in Mexico. It should be said that other scholars don’t accept this explanation, and continue to believe the book may be a hundreds-year old forgery, though they offer no explanation why any talented book artists in an earlier century would’ve gone to the trouble of creating a fake book.

Original post from November 30. 2011:

“A booke…containing nothing butt Hieroglyphicks, which booke his father bestowed much time upon: but I could not heare that hee could make it out.”–son of 16th century astrologer John Dee

I love mysteries like this. The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale houses the Voynich manuscript, named for the rare book dealer who acquired it ninety-nine years ago.

Prior to Wilfrid Voynich’s purchase of it, “the codex belonged to Emperor Rudolph II of Germany. . . who purchased it for 600 gold ducats and believed that it was the work of Roger Bacon,” the 13th century English mathematician.

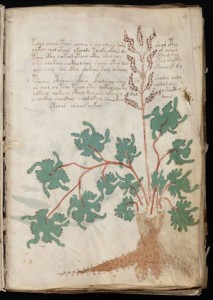

After Wilfrid Voynich died, it ended up at Yale when his widow sold it to another dealer, H.P. Kraus, who donated it to the Library in 1969. Though the Voynich, printed on vellum and covering some 240 pages, has been the object of much study by scholars and antiquarians, none has yet been able to decipher the language in which it’s written or discern its hidden meanings. The presentation, with dozens of illustrations, two sets of which are reproduced here, includes elements of a treatise on the cosmos, the zodiac, botanical life, human anatomy, and cooking. But the purpose of the book continues to elude even intensive examination.

This all puts me in mind of the astounding philological and linguistic accomplishments of J.R.R. Tolkien, who knew many ancient alphabets and languages, and invented more than a dozen for the denizens of Middle Earth. I’ve always loved the fact that Tolkien was on the editorial board of Doubleday’s Jerusalem Bible (1966). I recall reading that he was literate in Hittite, Aramaic, Akkadian, and Ugaritic, not to mention of course ancient Greek and biblical Hebrew.

In my naivete, it hadn’t occurred to me there are still written languages that remain terra incognita to classicists; the indecipherability of the Voynich manuscript seems to me the bibliographic analogue of anthropologists finding themselves unable to communicate with a hitherto unknown tribe they’ve discovered in the Amazon. Sadly, when tribes like that are happened upon they often suffer due to the sudden exposure and attention. Well, in the controlled humidity of the Beinecke I’m sure the Voynich ms. won’t be contracting the equivalent of a devastating disease, with crumbled and foxed pages, but exquisite preservation alone hasn’t brought the librarians and archivists any closer to riddling out the mysteries of the codex.