Neal Gabler’s Reporting for the NY Times Lends Credence to Ben Urwand’s “The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact w/Hitler”

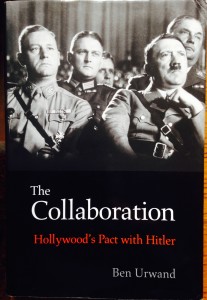

First, a refresher for readers who may not have seen several posts I wrote last fall I wrote about the revelatory book The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler by Ben Urwand, Junior Fellow of Harvard’s Society of Fellows, published by Harvard University Press:

First, a refresher for readers who may not have seen several posts I wrote last fall I wrote about the revelatory book The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler by Ben Urwand, Junior Fellow of Harvard’s Society of Fellows, published by Harvard University Press:

In one of those posts I had questioned what I saw as biased commentary on, unfair reviews of, and some weird carping about Urwand’s thorough, careful, and unsensational book about the failure of Hollywood moguls, most of them Jewish, to do much of anything to save Jews in Europe during WWII.

David Denby in The New Yorker had a shockingly censorious piece urging that the book be taken out of circulation until Urwand had revised it. Were such steps ever taken it would be an appalling abuse of free speech, violating the moral right of authors writing history to follow documentary evidence and publish their interpretation of events as they’ve come to understand them. The jaded Denby also claimed that much of what’s in the book was already known, but this missed the point: even if Denby’s post was accurate, can there no new or alternative interpretations of previously examined events, even plural interpretations, arrived at in good faith. Moreover, though, Urwand’s sources included archives and business records that no English-speaking historian had ever worked with, so how could the book have failed to contain new material? Denby never addressed those points, as I read him.

The push-back against Urwand’s book included attacks on him by Alicia Mayer, grand-niece of mogul Louis B. Mayer, who wrote on her website: “I need your help. Imagine for a moment that your family has been accused of collaborating with Hitler and the Nazis.” I urged media outlets to cover her accusations skeptically, taking into account her obvious personal stake in seeing that her great-uncle remain untainted by a critical historian. Another blogger critical of Urwand thought it somehow relevant to question his degree of observance as a Jew because it had been reported he ate a (non-kosher) lobster salad during an interview with a journalist.

Following my posts about Urwand and his book, his publicity tour brought him to the Museum of Tolerance in NYC on October 17, where I went to hear him lecture and meet him in person. The mid-30s Australian scholar’s talk was particularly illuminating, and personal. He began by explaining that he had actually been working on an academic thesis, about Hitler’s taste in movies, information that’s accessible because of Nazi records stating what he showed for himself, and guests, in frequent screenings he held.

Working on his paper, Urwand found records showing that, even before Hitler came to power—because of protests and agitation by Nazis with the weak Weimar regime—the German government lodged protests in Hollywood about “All Quiet on the Western Front,” produced by Jewish film executive Carl Laemmle, head of Universal Studios. He was a German-born Jew, by then living in the US. The movie, based on novelist Erich Maria Remarque’s global bestseller, depicted pacifism on the part of German soldiers’ in the WWI drama, inimical to the emerging nationalism and militarism in Germany. This sort of influence, flowing from Germany toward Hollywood—often including successful attempts at meddling in the actual scripting and editing of films—continued during the pre-war years, and then once the war began.

Thanks to the slides Urwand showed, he was able to illustrate the documentary trail of evidence he had followed in his research. A handful of those images may be viewed by clicking here.

After a flurry of coverage last fall about Urwand’s important book, The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler, things had quieted down until earlier this month when a lengthy article by film historian Neal Gabler, author of An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, was published in the New York Times. “Laemmle’s List: A Mogul’s Heroism” reported on the strenuous and often productive efforts of Laemmle to rescue imperiled Jews from Germany.

Though far as I know Gabler holds no special brief for Urwand, his article lends significant support to the thesis of The Collaboration.

For in his piece, Gabler writes,

“It may seem strange that Laemmle alone among the Hollywood chieftains—a group that included Adolph Zukor of Paramount, William Fox, Louis B. Mayer of MGM, Harry Cohn of Columbia and the Warner Brothers—sought to save Jews, since all of those studio heads were Jews themselves and nearly all of them had emigrated from Eastern Europe, over which Hitler was casting his ominous shadow. But almost from the inception of the American film industry, the Hollywood Jews were dedicated to assimilation, not religious celebration. They had come to America to escape their roots, not embrace them.”

It’s a pity that Carl Laemmle died so early in the war, 1939, or I bet he’d have saved yet many more German and European Jews. He was a good-hearted and generous man whose worries about the fate of many of his co-religionists consumed him to the point that his studio work was set aside while he lobbied Hollywood colleagues and such hard-hearted, anti-semitic officials in the US government as Secretary of State Cordell Hull.

I’m hopeful that the appearance of Gabler’s article will move some of Urwand’s critics to reconsider what I view as their reflexive and unreasonable opposition to his book. Watch this blog for further developments.