My Encounter With William Styron

The personal essay pasted in below chronicles a formative episode in my publishing career, when I had the privilege of working with William Styron on an Introduction to a nonfiction book that told the story of an innocent man on Death Row in Virginia. It was called Dead Run and Styron helped me champion it to a wide readership, even while he was engaged in the tormented struggle with depression and melancholy that he chronicled in his classic, Darkness Visible. BN Review published the essay in August 2011 and I have since submitted it to the editor of the annual anthology Best American Essays for consideration in their next collection to be published in Fall 2012. Other sites, such as the New Yorker’s Book Bench, byliner.com, zyzzva.org, and the National Book Critics Circle’s blog Critical Mass, mentioned and linked to the essay from their sites. It should also be noted that many of Styron’s great books are available as ebooks these days from Open Road Integrated Media.

The personal essay pasted in below chronicles a formative episode in my publishing career, when I had the privilege of working with William Styron on an Introduction to a nonfiction book that told the story of an innocent man on Death Row in Virginia. It was called Dead Run and Styron helped me champion it to a wide readership, even while he was engaged in the tormented struggle with depression and melancholy that he chronicled in his classic, Darkness Visible. BN Review published the essay in August 2011 and I have since submitted it to the editor of the annual anthology Best American Essays for consideration in their next collection to be published in Fall 2012. Other sites, such as the New Yorker’s Book Bench, byliner.com, zyzzva.org, and the National Book Critics Circle’s blog Critical Mass, mentioned and linked to the essay from their sites. It should also be noted that many of Styron’s great books are available as ebooks these days from Open Road Integrated Media.

—

August 1, 2011

In April of this year, Alexandra Styron published Reading My Father, a revealing memoir of her father, the great novelist and memoirist William Styron, best known for his novel Sophie’s Choice. A few weeks later, Styron’s longtime editor, Robert Loomis, announced his imminent retirement from Random House, where his 55-year career has made him a true publishing legend. Coming together, these events prompted my memory of a role Styron and Loomis played in a book I edited more than a decade ago, and testifies to the generosity—and moral passion—of both.

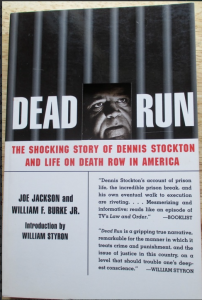

Combing through a stack of free books one day in 1997 during my early months as an executive editor at the Times Books division of Random House, I spied a copy of James L. W. West III’s William Styron: A Life, edited by Loomis. In it, West examined all the influences that shaped Styron’s literary art, among them his keen social conscience: his first piece of journalism on a social issue was a 1960 Esquire article arguing against the death penalty. Already an admirer of Styron and The Confessions of Nat Turner, I was fascinated with West’s insights into the roots of Styron’s socially conscious fiction. Some months after I read the biography, a literary agent happened to submit to me the manuscript by Joe Jackson and William F. Burke, Jr. that would become a nonfiction book titled Dead Run: The Shocking Story of Dennis Stockton and Life on Death Row in America.

Jackson and Burke open their narrative in 1983, during a searing Virginia summer. Despite substantial doubts raised at trial about Dennis Stockton’s involvement in a murder-for-hire scheme, he is convicted of the capitol offense and arrives on Death Row at Mecklenburg Correctional Center. Such was the force of the narrative that reading and rereading the draft manuscript, I felt like I’d spiked a fever each time I picked up the pages. Irresistibly, I’d find myself caged alongside Stockton amid the stifling heat behind those penitentiary walls, in a deep state of empathy. Stockton is unremittingly aware that he and his fellow inmates are subject to the caprice of the system: some will see their sentences stayed or even commuted, while others will inevitably make the slow journey to the electric chair. A handful of these desperate inmates, including Stockton, plan an audacious escape. Stockton is elected to be the driver of the prison van they’ll hijack. As their planning nears its climax, some of Stockton’s confederates come to believe he may be a turncoat, possibly informing against them to prison authorities. Tempers flare, Stockton denies the accusation, and the charge is withdrawn. Too late. Stockton tells them he’s out—he won’t be running with them the day they put their plan into gear.

Indeed when the fateful day arrives, Stockton, who has long wanted to be a writer, stays in his cell, putting it all down in a diary he’s begun keeping. Abetted by corruption among guards, the only mass escape from Death Row in American history is successful, as six convicted murderers flee. None of the “Mecklenburg Six” manages to stay on the lam for long, and all are back in prison within three weeks. But the breakout leads to a storm of controversy statewide. William Burke, an editor at the (Norfolk) Virginian-Pilot sends letters to the prisoners who didn’t run, asking how such an event could have occurred at the maximum security lockup. He invites anyone with a story to contact him. Stockton writes back, care of another inmate’s lawyer, “Well, I have this diary.”

The prisoner becomes a source. On September 16, 1984, a banner headline in the Pilot trumpets, “Diary Details Lax Prison Conditions.” The front-page story identifies Stockton as the diarist. While validating his writerly aspirations, publishing the journal was the most damaging thing Stockton could do to his reputation among prisoners and authorities. It marks him as essentially suspect, willing to share convicts’ private information and blow the whistle on official corruption, all before the public. Everyone distrusts him, or is hungry for vengeance. And so, over the next eleven years, Stockton endures every kind of hell, as he’s shuttled from one miserable cell to the next. Despite the key recantation of a trial witness made directly to Dead Run co-author and investigative reporter Joe Jackson, and evidence he accumulates suggesting others were involved in the crime, Virginia inflicts another injustice on Stockton. Courts invoke Virginia’s brutal twenty-one-day rule, stipulating that any new evidence must be produced within three weeks of conviction. If not, it will never be heard, no matter how compelling or persuasive. The efforts of Stockton, his lawyer, and investigative journalists are all quashed. He is executed on September 27, 1995.

I sensed that as a son of Virginia and a longtime opponent of the death penalty, Styron would be deeply disturbed and monumentally outraged at the conduct of his home state as revealed in the manuscript. Moreover, I was sure he would relate to the writer in Stockton, as his prison diary forms the emotional core of the book. Perhaps he’d feel motivated to contribute an endorsement or even an introduction to the book. I wrote a memo to Bob Loomis, whose office was on the floor above mine in the Random House building. Bob, courtly and solicitous, soon responded to my query and asked to see the manuscript. A few days later, Bob called me said, “You’re right, you have something here. We should get this to Bill.”

With Bob’s good offices propelling my effort, I sent Styron the manuscript. He read it promptly and told me he found it an important book. He promised me he would do something for it, and spoke of offering either a blurb or an introduction.

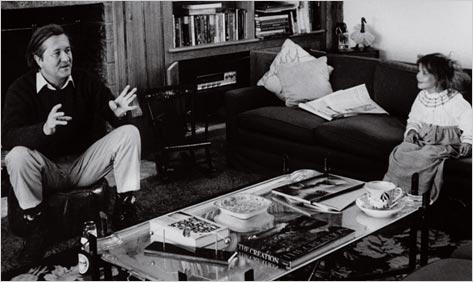

In the months that followed, while the authors and I edited and revised the manuscript, I was buoyed by the confidence shown in the book by both men, and I kept up regular contact with Styron. I became friendly with his secretary, Linda, who faithfully passed along my messages updating him on the edit and the exculpatory evidence about Stockton the authors continued to discover. I became familiar with Styron’s handwriting from notes he sent me, and envisioned him at work in the cottage that was his writing studio near the family’s main house in rural Connecticut. I gathered other blurbs and shared them with my Random House sales reps and publicists, who were already pitching the book to stores and libraries and pitching it to reviewers and show bookers, while reiterating Styron’s promise to contribute something. Still, I had nothing else from him to fuel their efforts. Each time we were in touch I nudged him, but didn’t feel comfortable pushing any harder.

Meantime, I kept an eye on the calendar and our rapidly advancing publication schedule. I worried that Styron’s own work demands and wavering health might in the end prevent him from making good on his pledge. I had read Darkness Visible when it was published in 1990, so I was aware of his history of disabling depression. What if an attack of malaise laid him low, and despite his sincere intentions, he was in the end unable to do anything for the book? I fretted over this possibility for months. Now I’ve read this in Alexandra Styron’s book: “In the spring of 2000, fifteen years after his first depression, my father once again heard ‘the wind of the wing of madness.’* Swiftly, he succumbed to a depression easily as fierce as his 1985 episode.”

But as it happened, William Styron and his family were spared this sad outcome for a year, and he delivered on his promise to me. Just as the book deadline was at hand, in spring of 1999, an introduction from Styron streamed out of my fax machine. His essay began with a powerful summation of Virginia’s history of capital punishment, harking back to colonial days:

In the Commonwealth of Virginia, the locale of Dead Run, the execution of felons has had a long and sturdy tradition. In fact, as the authors point out, no state in the union can claim a greater number of executions; this is partly due to Virginia’s status as the oldest political jurisdiction in America. But one has always had a sense that in the Old Dominion there exists a particularly strong lust for vengeance.

In 1,200 words he extolled the book, distilling its themes into meaningful lessons for readers about the failures of the criminal justice system:

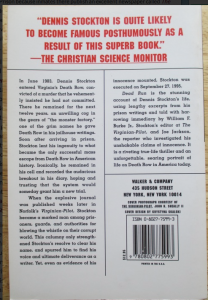

Dead Run is a gripping true narrative, remarkable for the manner in which it treats crime and punishment, and issues of justice in this country, on a level that should trouble one’s deepest conscience.

Editing the Introduction, I encountered what turned out to be for me a darkly amusing colloquy with Styron over one point. I gingerly explained to him that while the introduction disclosed the ultimate fate of Dennis Stockton, I had planned on not revealing the fact of his execution in our press materials and flap copy. I explained this in a fax of my own. The phone rang soon after. Styron intoned in his deep voice: “The specter of doom hangs over Stockton from the beginning of the book.” I chuckled a bit at my folly in overlooking this reality and accepted that we wouldn’t change this aspect of the Introduction. Meantime, though, he readily agreed to other revisions I’d suggested.

Later, seeing the introduction set in type for the first time he wrote me in his hand, “Thanks for the proofs, which look fine…. Thanks for keeping me abreast of developments. It’s a fine book.” And the next day, again by fax: “The change you made on p. vii is a good one. Thanks, William Styron.” Though I know from reading Alexandra Styron’s book that her father was prone to explosions of temper, despite my months of cajoling he never lost patience with me. I imagine such a dynamic is not unknown among the children of difficult parents—polite to strangers, abrupt or worse with family members.

As a person, I am not overly concerned about what people seem to think of me, nor do I crave lots of personal validation from others. Yet it’s an occupational hazard of the book business; as an editor and publisher I am invariably focused on what people think of my books—by colleagues inside publishing houses and among booksellers, agents, foreign scouts, critics, and readers. My aspirations for my books are often sustained by blurbs, reviews, and word-of-mouth, or deflated by the lack of them. In the case of Dead Run, I was blessed with the enthusiasm of Loomis and Styron, which nourished my hopes for the book with such ardency that I was inspired to mint a quip I’m still fond of sharing about my profession: “Being an editor allows me to express my latent religiosity, since I spend so much time praying for my books.”

Dead Run was published in November 1999 and received a huge amount of critical attention and praise, thanks no doubt to Styron’s Introduction and his name on the cover. It was reviewed across the country, in The New York Times Book Review, Washington Post Book World, San Diego Union-Tribune, Philadelphia Inquirer, Christian Science Monitor, Denver Post, and Richmond Times Dispatch, as well as in the legal press, including the New York Law Journal, the American Bar Association Journal, and the award-winning prison magazine, The Angolite. Canongate Publishers of Edinburgh, Scotland, bought the rights to bring it out in the U.K., while Walker & Company published it in trade paperback here in 2000, and it remains available today. Styron and I stayed in touch throughout publication and I sent the book to a list of people he compiled, including Mike Wallace, Art Buchwald, and Norman Mailer.

William Styron died in November 2006. A few months later St. Barthomolew’s Church in Manhattan was the site of a memorial service where friends and family honored the novelist’s work and life. The large sanctuary was filled with mourners and celebrants, a crowd that must have numbered in the thousands. The speakers included Bill Clinton, Ted Kennedy, Peter Matthiessen, Meryl Streep, Alexandra Styron, and Bob Loomis. At a reception afterward, I approached Rose Styron, whose activism and advocacy had dovetailed for so many years with her husband’s own passions and concerns. I introduced myself as the editor of a book called Dead Run, beginning to explain my connection with her late husband, and offering my condolences for her loss. But no explanation was necessary, as she quickly interjected, “Oh, Bill, loved that book. Thank you so much for sending it to him. He was so proud to contribute to it.” I was humbled to learn that the book had become a topic of discussion in the Styron household. Mumbling some thanks of my own, I let her move on to the next consoler.

Observing William Styron’s devotion to books of social conscience made a profound imprint on my career, shaping my own commitment to a type of book that I have repeatedly sought out and worked on since: works of truthtelling, whistleblowing, and muckraking that are informed by the experience of characters who’ve passed through a crucible of experience that leaves them transformed. These unique witnesses are also transformed in the eyes of the reading public, which confers elevated authority upon them. I am pleased and proud I could mark the publication of Alexandra Styron’s Reading My Father, and Robert Loomis’s retirement from Random House, with this remembrance of her father and his author, the indomitable William Styron.

*From Darkness Visible

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!