Appreciating Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker, and the Legacy of his Writing

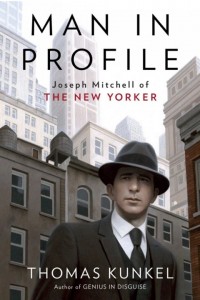

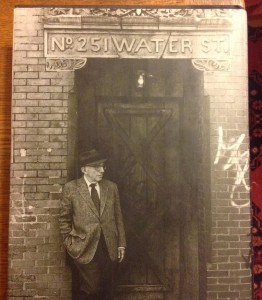

I spent the past couple weeks, amid so much disturbing upheaval in the world outside my reading, deeply enjoying Man in Profile: Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker, by Thomas Kunkel, which Random House published last June. (I had first shared about it on this blog last May.) From Kunkel’s acknowledgments at the end I’ve learned the book was commissioned by Bob Loomis*, the great editor there who, before his retirement in 2012, signed up the book, though the manuscript was evidently delivered after his departure. Mitchell grew up in a tobacco- and cotton-farming family in North Carolina (b. 1908) and, disappointing his father, moved to New York City at twenty-one, determined to become a newspaperman, even amid the Depression; he found work as a copy boy, and soon began reporting and writing, including at the Herald Tribune (where my longtime author, photojournalist Ruth Gruber later worked) and for the World-Telegram, which Mitchell joined in 1930. He began writing for The New Yorker in 1932, and joined the magazine’s staff in 1938. Kunkel’s book is a superb portrait of Mitchell’s whole life, to his death in 1996, and a rich appreciation of his writings.

I spent the past couple weeks, amid so much disturbing upheaval in the world outside my reading, deeply enjoying Man in Profile: Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker, by Thomas Kunkel, which Random House published last June. (I had first shared about it on this blog last May.) From Kunkel’s acknowledgments at the end I’ve learned the book was commissioned by Bob Loomis*, the great editor there who, before his retirement in 2012, signed up the book, though the manuscript was evidently delivered after his departure. Mitchell grew up in a tobacco- and cotton-farming family in North Carolina (b. 1908) and, disappointing his father, moved to New York City at twenty-one, determined to become a newspaperman, even amid the Depression; he found work as a copy boy, and soon began reporting and writing, including at the Herald Tribune (where my longtime author, photojournalist Ruth Gruber later worked) and for the World-Telegram, which Mitchell joined in 1930. He began writing for The New Yorker in 1932, and joined the magazine’s staff in 1938. Kunkel’s book is a superb portrait of Mitchell’s whole life, to his death in 1996, and a rich appreciation of his writings.

While reading and really savoring the whole book, every anecdote, every chapter it covers of Mitchell’s life, I took down from a bookshelf my copy of Up in the Old Hotel, the 1992 collection that gathered Mitchell’s profiles on true-life New York characters, and other work, which back then put Mitchell back on the map for many readers. Until then, his magazine pieces had frequently been gathered up and published between hardcovers—his first My Ears Are Bent, came out in 1938, followed by McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon (1943); Old Mr. Flood (1948); The Bottom of the Harbor (1959) and Joe Gould’s Secret (1965)—but it was more than two decades between books when, at the urging of Dan Frank of Pantheon Books, Mitchell published this full omnibus of his work, gathered from those books, and other sources. It made a big splash at the time, getting stellar reviews, and Kunkel tells us that Mitchell welcomed the spotlight that came with being remembered by so many readers, and discovered by even more.

I’ve had the book since soon after it came out—my copy’s a first edition. I was around that time editing and preparing to publish a comparable book, A Diary of Century: Tales from America’s Greatest Diarist, by Edward Robb Ellis, a near-contemporary of Mitchell’s, who also worked at the World-Telegram, arriving there in 1947. Like Mitchell, Ellis savored writing about memorable NY characters, people like Fred Bronnenkant, riveter for more than thirty years on the Brooklyn Bridge, who had such affection for the span he regarded it as a kind of mistress**. Though Eddie was not quite the consummate stylist that I now see Mitchell was, like Mitchell, he aspired to make great work. Both men learned writing in the same milieu—the midcentury American newspaper, entirely at NY papers for Mitchell, partly true for Ellis, who before coming to the metropolis to work at the World-Telegram (which in the 1950s tagged itself as “NY’s most ebullient newspaper”), had worked at papers in New Orleans, Oklahoma City, Peoria, and Chicago.*** They deployed vivid imagery, showed a fondness for lengthy list-making (a penchant embraced in more recent years by New Yorker writer John McPhee), a keen interest in what things cost back in the day, and an appreciation for character, with great skill at presenting to readers the people they encountered.

Seeing the success of Up in the Old Hotel, I recalling buying the book in hopes of imbibing some of that vibe and investing Eddie’s book with it. Though I was interested in Mitchell and his work, as happens for professional editors, I got sidetracked from it, and had in fact never read it thoroughly, nor really sensed the charms of Mitchell’s writing until the past couple weeks. During the weeks I was reading the Kunkel bio, I also leafed through the 700+page anthology, shown here, and now that I’ve finished the biography, I’m fully able to dive in to it. Last night, I read and enjoyed the third Profile in the anthology, about Mazie Gordon, a denizen of the Bowery, who ran a “moving-picture house” called the Venice Theatre, about whom “Detective Kain [of the Oak Street police station] says that she has the roughest tongue and the softest heart in the Third Precinct.” Mitchell chronicles her working life, seated in a glassed-in booth along Park Row, selling movie tickets, and greeting her patrons, some of whom are by her own description “bums” that live in nearby flophouses. She is a key player in the street life near Chatham Square, and the piece includes many conversations she had with bums, cops, priests, and all kinds of urban operators which it seems certain Mitchell overheard. His chronicle of Mazie’s proprietorship of the theatre, and her status in the wider neighborhood, is among the most enjoyable things I’ve read this year.

Here’s the first paragraph of the 1940 profile, titled ‘Mazie’:

“A bossy, yellow-haired blonde named Mazie P. Gordon is a celebrity on the Bowery in the nickel-a-drink saloons and in the all-night restaurants which specialize in pig snouts and cabbage at a dime a platter, she is known by her first name. She makes a round of these establishments practically every night, and drunken bums sometimes come up behind her, slap her on the back, and call her sweetheart. This never annoys her. She has a wry but genuine fondness for bums and is undoubtedly acquainted with more of them than any person in the city. Each day she gives them between five and fifteen dollars in small change….’In my time, I’ve been as free with my dimes as old John D himself,’ she says. Mazie has presided for twenty-one years over the ticket cage of the Venice Theatre.”

Now that I’m finished with the biography, I’ve also sought out reviews of it, such as a good one by John Williams in the NY Times, and a very insightful essay by Janet Malcolm in the NY Review of Books; she was a colleague of Mitchell’s at The New Yorker. Kunkel wrote an earlier biography of Harold Ross, founding editor of The New Yorker, who hired Mitchell for the magazine, after his several-year audition as a contributing writer. I’ve never met Kunkel, but I’m glad to say I feel connected to him anyway. As it happens, he reviewed Edward Robb Ellis’s A Diary of Century when it was published in 1995, with an Introduction by Pete Hamill, concluding his review in the Washington Post with the praise that Ellis’s diary of an Everyman, “produc[ed] something akin to Copland’s glorious ‘Fanfare for the Common Man.'” I’ll find a way to share this blog post with him, so I can belatedly let him know how glad I am that he enjoyed Eddie Ellis’s book, and I can tell him I felt the same for his superb book on Joseph Mitchell.

—

* Among Bob Loomis’s authors was William Styron; the courtly editor helped me enlist Styron’s aid in a championing a book I edited in 1999, about an arguably innocent inmate on Virginia’s Death Row. I wrote about that episode in my editorial career in an essay for the BN Review called “William Styron: A Promise Kept.”

**Ellis’s beguiling entry on Frank Bronnenkant is found on pgs 173-75 of A Diary of the Century (Kodansha America, 1995; republished by me at Union Square Press in 2008). Clicking on this link will take you to all my blog posts about Edward Robb Ellis, which includes one that examines the legacy of notorious faker Joe Gould, the subject of Mitchell’s last published profile; the recently discovered photographer, Vivian Maier; and Ellis, in a 2014 piece I titled “Vivian Maier Was the Real Deal, the Ultra-Opposite of Joe Gould.” The relevance here is that Ellis—whose book was drawn from his diary, a journal he began keeping at age 16, and which he stayed with until the year of his death at 89, the longest-kept such record in the history of American letters—and the secretly great and prolific street photographer Maier did each create a magnum opus, while Gould never did, though Mitchell did believe for a time that Gould really was writing a seminal work, “The Oral History of our Times.” And yet Mitchell, even after publishing two long profiles of Gould (‘Professor Seagull,’ ’42, rather credulous) and (‘Joe Gould’s Secret,’ ’64, not credulous any longer) did not rebuke Gould. He generously concluded that Gould, some writings by whom he had actually read in the 1940s, had perhaps at least been writing in his mind, as Mitchell did with an uncompleted memoir and novel he never published. I see a tragedy in that for Mitchell, but also kind of a decent-hearted triumph.

*** For her part, Ruth Gruber, before and after WWII, wrote for the Herald Tribune and the NY Post. Unlike Mitchell and Ellis, she oscillated in and out of journalism, working for a time in the federal government during the FDR Administration, as Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes’ special representative to Alaska from 1940-46. Ruth is, so far as I know, the eldest surviving member of the Franklin Roosevelt Administration. This post is about a 104th birthday gathering with her this past October.