Peat Bogs and Iron Age Humans

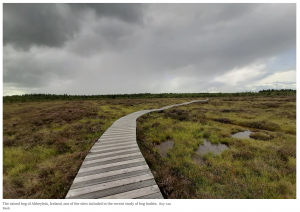

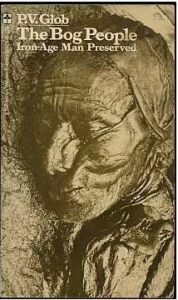

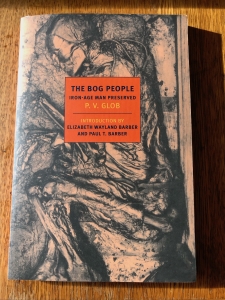

One of my most treasured books from my college days was The Bog People: Iron Age Man Preserved by Danish scholar P.V. Glob (a real name), chronicling the custom of people burying dead bodies in boggy ground. Such burials are found throughout Northern Europe. It is believed the practice began around 5000 BCE and diminished around 700 CE. Bogs are made of damp peaty soil, high in tannic acid and largely anaerobic, which had the affect of preserving the flesh, hair, clothing, fingernails, and even personal effects on the bodies. I had a mass-market Ballantine paperback published in 1973 (left with a cover photo of what became known as Tollund Man). I lost track of that copy some years ago, and have replaced it with a newer edition of the book, published by the NY Review of Books imprint (right).The new edition has prefatory material by the scholars Elizabeth Wayland Barber and Paul Barber, author of Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality.

One of my most treasured books from my college days was The Bog People: Iron Age Man Preserved by Danish scholar P.V. Glob (a real name), chronicling the custom of people burying dead bodies in boggy ground. Such burials are found throughout Northern Europe. It is believed the practice began around 5000 BCE and diminished around 700 CE. Bogs are made of damp peaty soil, high in tannic acid and largely anaerobic, which had the affect of preserving the flesh, hair, clothing, fingernails, and even personal effects on the bodies. I had a mass-market Ballantine paperback published in 1973 (left with a cover photo of what became known as Tollund Man). I lost track of that copy some years ago, and have replaced it with a newer edition of the book, published by the NY Review of Books imprint (right).The new edition has prefatory material by the scholars Elizabeth Wayland Barber and Paul Barber, author of Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality.

On January 30th, the NY Times published a fascinating update about the burial practice, reporting on a database maintained by scholars with more than 1000 known bog burials in such countries as Ireland, Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands. Archaeologists who’ve studied the sites and the bodies say some of them show evidence of violent treatment or even execution, perhaps incurred in the course of ritual or even sacrificial practice.

Despite what scholars in the Times article are describing, I don’t accept that all bog burials would’ve followed executions; it strikes me that at times a burial in a bog would have solved a challenge confronting mourners: how to inter or process the dead. Consider that if these 1000 burials have been found, these fifty centuries later, imagine how many multiples of that number there might have been bog burials down through the ages?

The images of the remains shown here cast my mind back uncounted generations when grieving families would’ve pondered how to inter their dead:

- How do we dig several feet into hard-packed earth?

- Who has a shovel, especially one that’s made from stout enough lumber and iron-forged steel so it won’t just snap in two?

- Best not leave the grave too shallow, lest the remains be found and torn by animals, as was invoked in the biblical story of Joseph and his brothers.

In some instances, placing the dead in swampy ground would have been the simplest option, one that offered mourners the greater likelihood that the body of their loved one would be undisturbed.

In addition, survivors feared the violation of a grave. Corpse robbery—theft of keepsakes like jewelry, or the skeleton itself in the case of a body snatcher (see Robert Louis Stevenson’s story The Body Snatcher) is something that occurred. I know some people must find the study of funerary practice lugubrious, but I never have.