Essay text, as read and spoken by me on January 3, 2013 for the Rust Belt Chic event at Public Assembly, Williamsburg in the Vol. 1 Brooklyn reading series. A related post, a blog piece on the whole evening, may be read via this link. Copies of Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology may be purchased from Cleveland-area retailers, online booksellers, and the RBC website. I urge you to support this unique expression of community literary spirit.

Remembering Mr. Stress, Live at the Euclid Tavern

Remembering Mr. Stress, Live at the Euclid Tavern

“Growing up in the hotbed of rock n’ roll that was Cleveland in the 60s and 70s, I began going to hear live music before I had even turned fourteen. Music Hall, with its fixed rows of seats trimmed in maroon velvet was a regular venue for bills such as Cream with Canned Heat; the Grateful Dead with the New Riders of the Purple Sage; Traffic; John Mayall; the Allman Brothers; and The Band, among many other acts. In 1972, just after turning eighteen, then Ohio’s legal drinking age, I began to discover live music venues that were even more fun as a hang-out than Music Hall.

On the eastern edge of University Circle, near Euclid Avenue and Ford Road was a squat red building known as the Brick Cottage, where I discovered that Mr. Stress, a venerable Cleveland bluesman often performed. Stress dubbed this club the “sick brick,” a rueful yet fond homage to the many nights of alcoholic excess committed within its walls. Mr. Stress was the Paul Butterfield of Cleveland—a white bluesman who sang and played harmonica and led his band with an unerring sense of what made the blues so entertaining and sustaining to live music lovers. He was always comfortable on stage with a cohort of diverse sidemen, young and old, black and white, tattooed players and professorial piano players.

In 1973, I went off to Franconia College in New Hampshire. By 1978, when I returned to Cleveland full-time, Stress and his band had moved up the block to the Euclid Tavern, at Euclid & 116th Street where they joined forces every Wednesday and Saturday night for a long-running residency. This club, a lot larger than the ‘Brick,’ included a central music room with a low stage for the band in front of a dance floor, an outdoor area in back, plus a basement bar. It was a veritable cruise ship of nightlife. During breaks between sets I often made new friends in my ambles around the lively deck. In the room opposite the stage was the main bar, a wide hitching post of a drinks station where multiple bartenders pulled beer taps and poured liquor. Above them was a sign that became a lifetime motto for me: ‘It’s hard to soar like an eagle when you’re on the ground with the turkeys.’

Mr. Stress—real name Bill Miller—was a TV repairman by day. ‘Stress,’ as most knew him, was a big reader, a history buff who avidly consumed books, including many on the Vietnam War and military history. In 1978, when my family and I began running Undercover Books, a bookstore in Shaker Hts., I’d order Nam books that Stress asked me about and bring them to the club for him. (Sometimes he paid for them, sometimes I just gave them to him–my personal payback to Stress for the enrichment he always lent the local music scene.)

Like me, many Stress fans came to the Euclid Tavern every week. I was friends with Danny Palumbo, who got around in a wheelchair. Danny worked for the State of Ohio in workplace compliance for accommodating the disabled. Never hindered in his enjoyment of the fine blues that Mr. Stress and the band put out, Danny would dance in his chair along with everyone else crowding the floor, boogieing to up-tempo numbers like “Crosscut Saw” and “Firing Line,” or swaying to laments such as the mournful ‘Black Night,’ when guest sax player Mal Barron would sometimes sit in. Danny had a colorful way of talking about the female friends he’d meet each week at the bar, and I recall him once saying of a certain Tanya, a particularly cute and curvaceous regular, that given the chance he’d eagerly ‘drink her bathwater.’

Another Stress fan I saw just about every week was Michael Lloyd, an African-American friend who like me had for a time worked at Municipal Stadium. We met when we were each vendors for Indians ballgames. I sold beer, Michael sold hot dogs. I did it for one summer, he did it for several and then moved in to the season ticket office. He was a tall and handsome fellow, with a smooth manner and sweet speaking voice. I thought of him as the Euclid Tavern’s Smokey Robinson of. He was a sharp dresser and a great dancer, and always drew to himself the prettiest, most statuesque new female visitors to the club. They would walk into the place, clearly wondering what this rough and raw place was all about; Michael would spot them and deftly take them under his wing for the night.

Stress enjoyed bantering with his bandmates and regulars got to know his repertoire very well. As Stress would reach the punch line to one of his hoary gags, a bartender would chime the tip bell, a badda-boom underlining the corny humor. One of Stress’s favorite lines was, ‘The more you drink, the better we sound.’

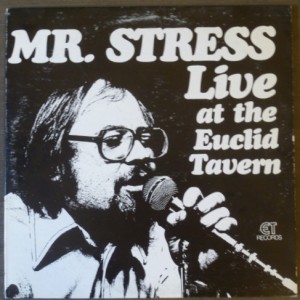

In the early 80s, Stress put out an album, ‘Mr. Stress Live at the Euclid Tavern.’ Here’s my copy of the LP, which I listened to while composing these recollections. I bought it before moving to New York City permanently in 1985. When visiting family back home, I would sometimes return to the club. Except for Stress with a new band, I never saw my old friends. It seemed people had moved on. As years passed, I occasionally wondered if he was still playing at the Euclid Tavern, or playing in Cleveland at all. I also wondered if the Euclid Tavern was still standing, even as the rest of University Circle underwent many makeovers and Cleveland picked itself up off the mat of urban decline time and again. While reporting this piece, I found a phone number for the establishment and asked a bartender if Mr. Stress still played there. Sounding a bit surprised, he replied, ‘No, he hasn’t played here for a couple years.’

Next I spoke with Plain Dealer reporter John Petkovic who’d written a 2011 story about Stress. He’d reported then that in 1993 the musician had had a heart attack. Stress also told Petkovic, ‘I woke up one morning and. . . I had lost a third of my vision. I’ve heard it comes from [a harmonica player] blowing so hard, you pop blood vessels. I can’t drive or get around as well. But it ain’t stopping me from playing the blues.’

Petkovic referred me to Alan Greene, a Cleveland musician who played gigs with Stress as late as 2010. Alan told me Stress is still living and now considers himself in ‘semi-retirement.’ Alan also mentioned that New Year’s Day 2013 Stress will turn seventy, which brought back a flood of rich memories from great New Year’s Eve shows when Stress and revelers raucously marked a new year and Bill’s birthday. Alan also mentioned that when Stress was born, a minute after midnight on New Year’s Day in 1943, he was feted as Cleveland’s firstborn of the new year—a fitting birth for a bluesman if you think of Muddy Waters singing about the fabled blues character ‘born the 7th son of a 7th mother on the 7th day.’ Clearly, Mr. Stress had an auspicious pedigree for a bluesman.

Living in New York City today I remain a devotee of going out to hear live music, a happy habit I began forty years ago listening to Mr. Stress. I must add that after Rust Belt Chic was published, Mr. Stress read my essay and we’ve been reunited via telephone and the Internet after more than 25 years being out of touch. He’s very glad to see his career remembered in this book. Even with macular degeneration, he still reads voraciously with aid of voice-enabled software. We were in touch on his birthday New Year’s Day and he knows I’m presenting his story here tonight.”

With my friend Steve Conte–owner of FunnyBooks, the comics store in Lake Hiawatha, NJ–we are today announcing the launch of R3NYNJ, a fan group in the NYC metropolitan area to celebrate Canadian indie rock n’ roll, borrowing our name from CBCRadio3, the fabulous Internet radio station based in Vancouver that is such a rich portal for the work of 100s of great Canadian musicians, many of whom have international followings, or will have fans worldwide. Under the banner of this new logo (inspired design by Steve), and the Twitter hashtag, #R3NYNJ, we will

With my friend Steve Conte–owner of FunnyBooks, the comics store in Lake Hiawatha, NJ–we are today announcing the launch of R3NYNJ, a fan group in the NYC metropolitan area to celebrate Canadian indie rock n’ roll, borrowing our name from CBCRadio3, the fabulous Internet radio station based in Vancouver that is such a rich portal for the work of 100s of great Canadian musicians, many of whom have international followings, or will have fans worldwide. Under the banner of this new logo (inspired design by Steve), and the Twitter hashtag, #R3NYNJ, we will