In May 2001, Avalon Publishing Group–the Berkeley, California company I worked for as an editorial executive with Carroll & Graf Publishers–moved all its New York employees to new offices on 161 William Street in lower Manhattan, near City Hall Park, behind Park Row and the J&R Music World stores, 2-3 blocks east of the World Trade Center. I had enjoyed our original space on W. 21st Street, and didn’t appreciate the longer commute from my apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, but soon got used to the new neighborhood, new restaurants, new sights and sounds.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, I rode the #1 train downtown and emerged from the Fulton Street subway station, at the corner of William and Fulton, with a customary single earbud stuck in one ear, tuned in to local public radio station WNYC, alert to what might be going on at street level. I detected uncharacteristic alarm from the on-air voices of host Brian Lehrer and correspondent Beth Fertig. Before I could comprehend the source of their concern, my gaze turned west and up in to the air toward the World Trade Center towers, startled to see flames, smoke, and debris pouring from the structures, against a backdrop of a California-type deep blue sky. The air around me was palpably hot, a weird sensation I couldn’t account for, even after seeing the flames above me in the sky.

What in the world?

Turning the corner and hurrying toward my office building, I focused again on the radio voices, hearing something about an airplane having crashed into one of the towers, and then, that a second such crash had occurred, evidently only moments before I came out of the subway. Lehrer’s and Fertig’s alarm was in real time. Any idea I had momentarily entertained that associated this event with the incident in the 1940s when the Empire State Building was struck by a light plane, was dashed. I ran in to 161 William, took the elevator to our upper floor and found a handful of Avalon colleagues who’d arrived before me. I hustled over to the western side of the floor, joining them as we all took in a clear view of the twin towers, with a valley of lower buildings below and between us and the conflagration. The volume of flame, smoke, and debris were all much greater than when I’d first seen them from street level. The debris included a fluttering cascade of myriad loose sheets of white paper. Midway between our building and the two towers I noticed a lone man on a rooftop across the way and below our floor. The figure seemed to be in a prayerful pose, kneeling on a rug, wearing a white skullcap. I never learned what he was doing there, and have in the years since pondered it with colleagues such as Keith Wallman who saw the man with me that morning.

In those days, neither my wife nor I owned a cell phone. I rushed into my office, on the east side of the building, and used my phone there to call Kyle. The lines worked the first time I tried our home line. She’d just gotten in from taking our son Ewan to kindergarten, where he was in his first week as a student; on her way home she’d heard about the events downtown. I told her what I’d seen and she said she had the TV on and warned me to leave the office building right away. I said, yes, but I don’t know what’s going on at street level. What if the buildings fall, and topple in the easterly direction? What if people are panicked or trampling each other? Maybe I’d be safer upstairs. These were some of my thoughts. Kyle said she was going to go out and get cash and drinking water for our apartment, then go back to school and bring Ewan home. We talked a few minutes more and I told her I was going to go back to the other side of the office, the west side of the floor, to see the latest developments. I stayed a few minutes and finally decided, yes, it’s time to leave. I tried my home line again but now couldn’t get a call through. I would’ve left a message, telling Kyle I was leaving and that I would try to call her again later, but couldn’t get through at all. A colleague and I decided to descend in the elevator together, and then make a run for it when we got out on William Street. My companion was my fellow editor Tina Pohlman. As we were rushing from the western windows in to the open elevator car—I know now it was at 9:59 AM—we heard one of the weirdest sounds I’ve ever experienced, made by what I learned later was the collapse of the first tower. First, came a deeply guttural bass sound, created probably by the tremendous downdraft of air from the vertical collapse—something almost felt more in my belly than heard in my ears. The next instant, I registered a high, trebly, tinkling noise made up, I think, of breaking glass and splintering metal.

Tina and I descended in the elevator without a problem, but outside the lobby’s revolving door saw hundreds of people running past our building front, engulfed in a dusty, smoky cloud. Without hesitating more than a few seconds, we pushed out the door and joined the massing throng pushing north and east, toward the Brooklyn Bridge. Tina hoped to head over to the lower East Side, where she lived, if permitted by police. My direction was uptown, all the way to West 102nd Street, my home block. We were immediately surrounded by the cloud, a murk that wasn’t pure gray or black, examples that TV footage would later show; this cloud actually had a few shafts of sunlight in it. It was more ochre than gray. Still, it was pretty opaque and a specific fear registered that if debris were flying in it, we might not even see it heading at us. We made a right turn on Beekman Street, past New York Downtown Hospital, then turned left on Pearl Street, running together for several blocks until we were actually under the Brooklyn Bridge.

Though still surrounded by the blanket of dust, and impelled to keep running till I was clear of it, I was beginning to fear that I couldn’t keep up the pace. I wasn’t so much out of breath, the problem was the shoes I had worn that morning—a pair of newish ankle-high boots. With the beautiful fall weather that morning, I had considered them appropriately autumnal and so decided to don them. But I hadn’t broken them in yet, and they proved terrible to try to run in, or even to try walking fast. I would regret my choice of footwear for many months that followed.

I tried to ignore the nascent pain and resumed my nervous, awkward jog, continually hitching and hauling up the tote bag slung over my shoulder. Surrounded by earnest and fearful strangers, all of us still shrouded by the murk, my route passed through unfamiliar parts of Chinatown. Approaching Canal Street the cloud began to thin a little. Finally, we crossed Canal and burst into patches of clear air. Tina and I said goodbye and wished each other well as we headed off in our separate directions. I was relieved to be in clearer air and thought, Now I just have to get home. Problem was, I still had a long way to go. Any city buses that passed were insanely overcrowded, and moving at a crawl anyway. Yellow cabs and livery taxis were also full and barely moving through the dense surface traffic. Continuing to listen to the radio, I learned that the second tower had fallen, at 10:28. With both towers down, I was now confirmed in my horror that thousands of people had already died this day. Meantime, the subways had been halted, and it was unknown when they would resume operation. I had no choice but to walk all the way home, about eight miles.

I pushed up Broadway, through Soho, past Union Square, the Flatiron Building, Madison Square, Times Square, the Theater District, Central Park, Columbus Circle, and Lincoln Center. Every now and then on this odyssey I’d stop and try Kyle on a pay phone. The lines were all dead. She didn’t know when or even for sure if I had left my office. At last, I hit 72nd Street and was on the Upper West Side. It felt good to be back uptown, but I still had thirty blocks to go. I kept pushing, increasingly hobbled, eventually ringing our bell and announcing I was home. It was around 3PM, about five hours since I’d left William Street. Kyle and Ewan were waiting for me and I collapsed into their open arms. I sat down and removed my shoes and socks. Both feet were raw and blistered, from ankles to toes. I tuned in to TV for the first time all day and saw with my own eyes the enormity of the loss that everyone else had been viewing all day via the visual medium. Not wanting to disturb Ewan any more than he might be already, we shut off the set until he went to bed.

Avalon’s offices would remain closed for about a week and a half. I tried to stay off my feet and let them heal, but the need to be ambulatory prevailed and I resumed walking around. Unfortunately, my gait was much altered by what I’d endured, which led to a series of foot, ankle, calf, hamstring, and leg injuries over the next couple years. Damage to the #1, 2, and 3 subway lines in lower Manhattan was so serious that my longer commute was lengthened further; a trip that used to take 30-40 minutes often ran to 90 minutes or longer, with a lot more walking required every day. It was a horrible burden every day to come to work in the same neighborhood with the toxic brew a few blocks west that was already making recovery workers on the pile ill. For some reason, cold air seemed to magnify the odor that drifted eastward in the neighborhood. On winter evenings, I would leave the office and rush down in to the subway station, covering my mouth with a handkerchief to cut the horrible, vile crippling smell that I knew contained a mix of plastics, circuit boards, burnt upholstery, carpets, and human remains.

A new normal kind of took over, but nothing really seemed normal anymore. I read about and followed the 9/11 Commission and was appalled at what had been the Bush administration’s failure to heed urgent warnings from counter-terrorism officials, as we were reminded again this morning with Kurt Eichenwald’s NY Times Op-Ed, The Deafness Before the Storm. I was deeply and personally offended when Bush held his 2004 convention in NYC, using the still-healing city as a backdrop for his bogus triumphalism. He and Dick Cheney claimed to have kept us safe–except I always hastened to add–when they had failed, “big time,” to borrow a phrase of Cheney’s. I was enormously relieved when Avalon moved offices again, back into Chelsea, a welcome removal from the still-stricken neighborhood downtown.

I didn’t suffer personal loss that day, but the mundane insults that many denizens of Gotham did endure—my leg injuries and lengthened commute standing for the ordinary pain of so many—were deeply hurtful, especially knowing that so many had lost so much more. Then came Bush’s invasion of Iraq, and the recession only seven years after 9/11—that’s some string of national bummers, as our politics became more and more corrosive. It’s hard to overcome feeling sad, but I do, mostly.

Each year on 9/11 our UWS neighborhood welcomes mourners, firefighters, police, and families to the Fireman’s Memorial on Riverside Drive at 100th Street, a civic monument originally erected in 1913. Last year, on the tenth anniversary of 9/11, the day’s observances drew firefighter crews from all over the U.S., anglophone and francophone Canada, Scotland, France, and Australia. I’ll conclude this personal remembrance of September 11, 2001, and its aftermath by sharing nine of the photographs Kyle and I took at the special day last year. I will close by saying I hope your 9/11 anniversary this year, 2012, has been a soothing day. Shalom.

-

-

Many fine moustaches were in evidence among the visiting firefighters on the 10th anniversary of 9/11.

-

-

Three fine gentleman firefighters.

-

-

Well and truly–the Pride of Midtown.

-

-

Many proud firefighters in hats.

-

-

I wasn’t the only one who wanted to take their picture.

-

-

Note the Canadian maple leaf shoulder patch. Firefighters from Ontario and Quebec visited New York for 9/11/11.

-

-

These two fine fellows from Scotland became our fast friends for an hour on 9/11/11.

-

-

“Sapuers Pompiers De France”

-

-

Fireman’s Memorial, 100th St. & Riverside Drive. On 9/11 we always hear the sound of bagpipes in our neighborhood.

When I was an editorial executive at Carroll & Graf Publishers from 2000 until 2007, Nick Robinson was a frequent publishing partner based in the UK. His company, Constable & Robinson, brought out many books in Britain that we then published in North America. Each publishing season there were between 10-20 titles. Mysteries, solid nonfiction like Jack Holland’s Misogyny: The World’s Oldest Prejudice, and lots of books that just balanced our list very well. A backbone of our program with them were the editorially smart, superb value-oriented series of Mammoth Books, with well over 75 titles in the program, some of them shown below. My senior colleague Herman Graf first met Nick in 1983. They worked together very closely, meeting in London and NYC and at the int’l book fairs. When I began attending the Frankfurt Book Fair for my new company I had the good fortune to meet Nick and work with him, too. He liked that I’d been a bookseller before I became an editor. Nick hired people well and so had great colleagues who always attended our group dinners in Frankfurt, including one female executive, Nova. At those dinners, he was always cheerful and funny, showed great knowledge of food and wine, and always called for a toast and set aside time for all to savor our collective moments together.

When I was an editorial executive at Carroll & Graf Publishers from 2000 until 2007, Nick Robinson was a frequent publishing partner based in the UK. His company, Constable & Robinson, brought out many books in Britain that we then published in North America. Each publishing season there were between 10-20 titles. Mysteries, solid nonfiction like Jack Holland’s Misogyny: The World’s Oldest Prejudice, and lots of books that just balanced our list very well. A backbone of our program with them were the editorially smart, superb value-oriented series of Mammoth Books, with well over 75 titles in the program, some of them shown below. My senior colleague Herman Graf first met Nick in 1983. They worked together very closely, meeting in London and NYC and at the int’l book fairs. When I began attending the Frankfurt Book Fair for my new company I had the good fortune to meet Nick and work with him, too. He liked that I’d been a bookseller before I became an editor. Nick hired people well and so had great colleagues who always attended our group dinners in Frankfurt, including one female executive, Nova. At those dinners, he was always cheerful and funny, showed great knowledge of food and wine, and always called for a toast and set aside time for all to savor our collective moments together.

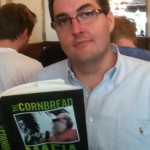

This morning I met an author whose work I really admire. My breakfast mate was Jim Higdon, author of The Cornbread Mafia: A Homegrown Syndicate’s Code of Silence and the Biggest Marijuana Bust in American History, which is officially released tomorrow. I’d never met Jim, though I had a role in insuring that his book had a chance to get published. When I read the draft manuscript I wasn’t in a position to publish it myself, but I really enjoyed this gonzo true-crime narrative, and so recommended it to longtime Carroll & Graf colleague and friend, Keith Wallman, now an editor at Lyons Press. It was precisely the sort of book he and I combined to edit and prepare for publication many times, with books like David Pietrusza’s Rothstein: The Life, Times, and and Murder of the Criminal Mastermind Who Fixed the 1919 World Series; Barbara Raymond’s The Baby Thief: The Untold Story of Georgia Tann, the Baby Seller Who Corrupted Adoption; Alan Bisbort’s “When You Read This, They Will Have Killed Me”: The Life, Redemption, and Execution of Caryl Chessman, Whose Execution Shook America; and Chuck Kinder’s Last Mountain Dancer: Hard-Earned Lessons in Love, Loss, and Outlaw Honky-Tonk Life, to name only four of many dozen books we published together.

This morning I met an author whose work I really admire. My breakfast mate was Jim Higdon, author of The Cornbread Mafia: A Homegrown Syndicate’s Code of Silence and the Biggest Marijuana Bust in American History, which is officially released tomorrow. I’d never met Jim, though I had a role in insuring that his book had a chance to get published. When I read the draft manuscript I wasn’t in a position to publish it myself, but I really enjoyed this gonzo true-crime narrative, and so recommended it to longtime Carroll & Graf colleague and friend, Keith Wallman, now an editor at Lyons Press. It was precisely the sort of book he and I combined to edit and prepare for publication many times, with books like David Pietrusza’s Rothstein: The Life, Times, and and Murder of the Criminal Mastermind Who Fixed the 1919 World Series; Barbara Raymond’s The Baby Thief: The Untold Story of Georgia Tann, the Baby Seller Who Corrupted Adoption; Alan Bisbort’s “When You Read This, They Will Have Killed Me”: The Life, Redemption, and Execution of Caryl Chessman, Whose Execution Shook America; and Chuck Kinder’s Last Mountain Dancer: Hard-Earned Lessons in Love, Loss, and Outlaw Honky-Tonk Life, to name only four of many dozen books we published together.

When I

When I