John Le Carré RIP + How the Cold War Began

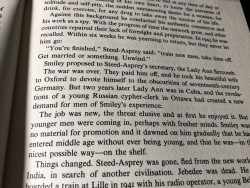

Dec 24, 2020—After putting up the post below in tribute to John Le Carré, I began reading his first novel Call for the Dead, which I had photographed copies of for the post. Right away, on page 7, I was sorta stunned to find a reference to a key historical episode, often overlooked or forgotten nowadays, that had been documented in a book I acquired and published fifteen years ago. The narrator of Le Carré’s compact, 128-page Cold War thriller explains why protagonist George Smiley, a British intelligence officer from just after the end of WWI to 1943, emerged from retirement just as WWII was ending. The reason was “The revelations of a young Russian cypher-clerk in Ottawa [which] had created a new demand for men of Smiley’s experience.” That cypher-clerk was Soviet defector Igor Gouzenko, whose defection author Amy Knight wrote about in her 2005 book, How the Cold War Began: The Igor Gouzenko Affair and the Hunt for Soviet Spies. Her nonfiction book tells an amazing story of how Gouzenko, with his wife and children in tow, left Soviet quarters intending to defect, but struggled to find an embassy that would give him asylum. He was the first defector of the Cold War, and it was still in 1945! He became something of a media sensation in Canada, and would later appear in media there with a hood over his face to disguise his identity, as seen on he cover of the edition we brought out.

Dec 24, 2020—After putting up the post below in tribute to John Le Carré, I began reading his first novel Call for the Dead, which I had photographed copies of for the post. Right away, on page 7, I was sorta stunned to find a reference to a key historical episode, often overlooked or forgotten nowadays, that had been documented in a book I acquired and published fifteen years ago. The narrator of Le Carré’s compact, 128-page Cold War thriller explains why protagonist George Smiley, a British intelligence officer from just after the end of WWI to 1943, emerged from retirement just as WWII was ending. The reason was “The revelations of a young Russian cypher-clerk in Ottawa [which] had created a new demand for men of Smiley’s experience.” That cypher-clerk was Soviet defector Igor Gouzenko, whose defection author Amy Knight wrote about in her 2005 book, How the Cold War Began: The Igor Gouzenko Affair and the Hunt for Soviet Spies. Her nonfiction book tells an amazing story of how Gouzenko, with his wife and children in tow, left Soviet quarters intending to defect, but struggled to find an embassy that would give him asylum. He was the first defector of the Cold War, and it was still in 1945! He became something of a media sensation in Canada, and would later appear in media there with a hood over his face to disguise his identity, as seen on he cover of the edition we brought out.

Amy Knight has since become a client of my literary agency; I sold her book Orders to Kill: The Putin Regime and Political Murder to St Martin’s in 2017, and we will be working to sell another Russia-related book by her in 2021.

Original post below from Dec 15:

—–

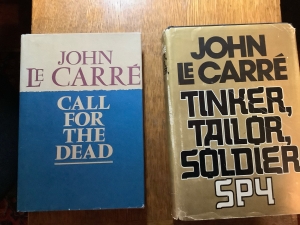

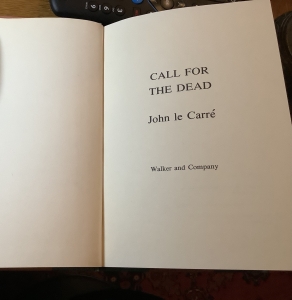

In honor of the late spymaster John Le Carré, who passed this week at age 89, I was happy to take these handsome copies off a bookshelf in my library. Call for the Dead is a particularly fine copy, a first US edition of his first novel that I found in a Maine antique store in the 1990s, published here by Walker & Company in 1961. By happenstance I was an editor at Walker in 1987, where I had the mantle of publishing espionage fiction, which is when I learned that Walker was Le Carre’s first US publisher, later bringing out The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

In honor of the late spymaster John Le Carré, who passed this week at age 89, I was happy to take these handsome copies off a bookshelf in my library. Call for the Dead is a particularly fine copy, a first US edition of his first novel that I found in a Maine antique store in the 1990s, published here by Walker & Company in 1961. By happenstance I was an editor at Walker in 1987, where I had the mantle of publishing espionage fiction, which is when I learned that Walker was Le Carre’s first US publisher, later bringing out The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

The copy of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy pictured here published in 1974 by Knopf, is also a first edition, and the copy of the book that my late brother Joel and I read of the book.

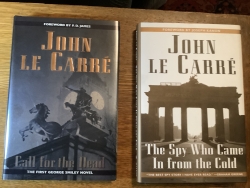

In 2004, a book business friend George Gibson, then publisher at Walker, now with Grove Atlantic, harked back to Walker’s early days by reissuing Call for the Dead with a Foreword by P.D. James, and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold with Joseph Kanon providing the Foreword.

#espionage #books #spies

Hiding in plain sight is confirmation in

Hiding in plain sight is confirmation in