My Contribution to “Rust Belt Chic: A Cleveland Anthology”

Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology is officially published now and available for purchase, as a trade paperback and an ebook. This is the book readers and friends may have noticed me, and others, blogging about over the past couple months. I posted about it on July 13, just after I’d submitted my completed essay, “Remembering Mr. Stress, Live at the Euclid Tavern,” on a venerable Cleveland bluesman and the nightclub where he and his excellent band played for many years, both of which proved personal gateways to my lifelong enjoyment of live music.

Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology is officially published now and available for purchase, as a trade paperback and an ebook. This is the book readers and friends may have noticed me, and others, blogging about over the past couple months. I posted about it on July 13, just after I’d submitted my completed essay, “Remembering Mr. Stress, Live at the Euclid Tavern,” on a venerable Cleveland bluesman and the nightclub where he and his excellent band played for many years, both of which proved personal gateways to my lifelong enjoyment of live music.

Before making way for my piece, I want to add that Rust Belt Chic is a unique community publishing project, spearheaded by co-editors Anne Trubek and Richey Piiparinen, who pulled the whole project together, with more than 35 contributors, in under 3 months. It comes at a propitious moment, a time to appreciate and re-appreciate what weathered cities like Cleveland offer the country–creativity, resiliency, new hope, authenticity, and less bullshit than other environs. After seven years of running Undercover Books in Cleveland, I left my hometown, moving to New York City in 1985. Even here in the metropolis, I note the mall-ification and mass-ification of the city, where it seems every corner has a Duane Reade, CVS, Walgreen’s, TD Bank, HSBC, Chase, or Citibank. What ever happened to stores run by local owners? Well, they’re around, just a bit harder to find, in NYC, and many in Cleveland. This is the sort of new world that Rust Belt Chic explores and chronicles.

As a sign of just how community-oriented the book really is, editors Trubek and Piiparinen asked all the contributors, in the event that the book sells well enough to make back its expenses and reaches into profitability, would we want an honorarium payment, or would we choose to plow our earnings into another indie project to be chosen first from among book ideas presented by us contributors, with one (or if we’re really fortunate, more than one) project being chosen for funding. I have a ready book idea–a new volume to be culled from the Guinness Book of World Records-recognized diary of Edward Robb Ellis, whose A Diary of the Century: Tales from America’s Greatest Diarist, I edited and published in 1995. I was happy to choose the second option offered.

With all that said, I’ll close this preamble by saying I hope you buy the book as a print or a digital edition, or one of each, not because of charitable intentions (though that’s okay too) but because it offers thirty-five fine examples of narrative journalism, chronicling a distinctive part of the country that is too often overlooked on the literary and cultural map. I also urge you to follow the book’s Twitter feed, @rust-belt-chic. On my own Twitter feed, @philipsturner, I’ve started a hashtag, #MrStress. You may also ‘like’ the Rust Belt Chic Facebook page. Thank you in advance for supporting this exciting experiment in cultural urban renewal.

—-

Remembering Mr. Stress, Live at the Euclid Tavern

Growing up in the hotbed of rock n’ roll that was Cleveland in the 60s and 70s, I began going out to hear live music even before I had turned fourteen. Music Hall, with its fixed rows of seats trimmed in maroon velvet was a regular venue for bills such as Cream with Canned Heat; the Grateful Dead with the New Riders of the Purple Sage; Traffic; John Mayall; the Allman Brothers; and The Band, among many other acts. In 1972, just after turning eighteen, then Ohio’s legal drinking age, I began to discover live music venues that were even more fun as a hang-out than Music Hall.

On the eastern edge of University Circle, near Euclid Avenue and Ford Road was a squat brick building known as the Brick Cottage, where I found that a venerable Cleveland bluesman, Mr. Stress and his band often performed. Stress dubbed this club the “sick brick,” a rueful yet fond homage to the many nights of alcoholic excess committed within its walls. Mr. Stress was the Paul Butterfield of Cleveland—a white bluesman who sang and played harmonica and led his band with an unerring sense of what made the blues so entertaining and so sustaining for live music lovers. He was always comfortable on stage with a cohort of diverse sidemen, young and old, black and white, tattooed players and professorial pianists.

In 1973, I went off to study at Franconia College in New Hampshire. By 1978, when I returned to Cleveland full-time, Stress and his band had moved down the block to the Euclid Tavern, at 116th Street where they would join forces every Wednesday and Saturday night for what became a long-running residency. This club, quite a bit larger than the “Brick,” included a central music room with a low stage for the band and a dance floor, an outdoor area in back, plus a basement bar. It was a veritable cruise ship of nightlife. During breaks between sets I often made new friends in my ambles around the lively deck. In the room opposite the stage was the main bar, a long hitching post of a drinks station where multiple bartenders pulled beer taps and poured liquor. Behind and above them was a sign that became a watchword in my life: “It’s hard to soar like an eagle when you’re on the ground with the turkeys.”

Mr. Stress—real name Bill Miller—was a TV repairman by day. “Stress,” as most people called him, was a big reader, a history buff who avidly consumed books, including many on the Vietnam War. In 1978, when my family and I began running Undercover Books, a bookstore in Shaker Hts., I’d order Nam books that Stress asked me about and bring them to the club for him. (Sometimes he paid for them, sometimes I just gave them to him—my personal payback to Stress for the generous enrichment he always lent to the Cleveland music scene.)

Like me, many Stress fans came to the Euclid Tavern every week. I was friends with Danny Palumbo, who got around in a wheelchair. Danny worked for the State of Ohio in workplace compliance for accommodating the disabled. Never hindered in his enjoyment of the fine blues that Mr. Stress and the band played, Danny would dance in his chair along with everyone else crowding the wooden dance floor, boogieing to up-tempo numbers like “Crosscut Saw” and “Firing Line,” or swaying to laments such as the mournful “Black Night,” when a guest sax player, Mal Barron, would sometimes sit in. Danny had a colorful way of talking about the female friends he’d meet each week at the bar, and I recall him once saying of a certain Tanya, a particularly cute and curvaceous regular, that given the chance he’d eagerly “drink her bathwater.”

Another Stress fan I saw just about every week was Michael Lloyd, an African-American friend who like me had for a time worked at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium. We met when we were each vendors for Cleveland Indians baseball games. I sold beer, Michael sold hot dogs. I did it for only one summer, he did it for a few more and then moved in to the season ticket office. He was a tall, handsome fellow, with a smooth manner and sweet speaking voice. I thought of him as the the Euclid Tavern’s Smokey Robinson. He was a sharp dresser and a great dancer, and always drew to himself the prettiest, most statuesque new female visitors to the club. They would walk tentatively into the place, clearly wondering what this rough and raw place was all about; Michael would spot them and deftly take them under his wing for the night.

Stress enjoyed bantering with his bandmates and regulars got to know his comic repertoire very well. As Stress would reach the punch line to one of his hoary gags, a bartender would chime the tip bell, a badda-boom underlining the corny humor. The exterior of the building that housed the Euclid Tavern was as weathered as the nearby streets. One of Stress’s favorite lines was, “The more you drink, the better we sound.”

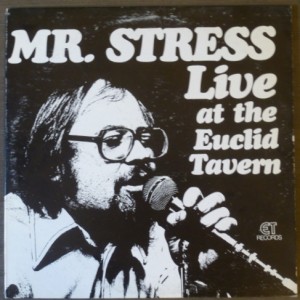

Sometime in the early 80s, Stress put out an album, “Mr. Stress Live at the Euclid Tavern.” I still treasure my vinyl LP, and listened to it while composing these recollections. After moving to New York City in 1985, I would sometimes return to the club when visiting family back home. Except for Stress, I never saw the old crew. As years passed, I occasionally wondered if he was still playing at the Euclid Tavern, or playing in Cleveland at all. I also wondered if the Euclid Tavern was still standing at 116th Street, even as the rest of University Circle underwent many makeovers and Cleveland picked itself up off the mat of urban decline time and again. My sister Pamela Turner still lives in Cleveland, and in July she found it for me, taking the photo of the sign posted here. While reporting this piece I found a phone number for the establishment and asked a bartender who answered if Mr. Stress still plays there. Sounding a bit surprised, he replied, “No, he hasn’t played here for a couple years.”

I later spoke with Plain Dealer reporter John Petkovic who’d written a 2011 story about Stress, reporting that in 1993 the musician had had a heart attack. In the story, Stress also told Petkovic, ““I woke up one morning and. . . I had lost a third of my vision. I’ve heard it comes from blowing so hard, you pop blood vessels. I can’t drive or get around as well. But it ain’t stopping me from playing the blues.”

Petkovic referred me to Alan Greene, a Cleveland musician who played gigs with Stress as late as 2010. Alan said Stress now considers himself in “semi-retirement.” Alan also mentioned that next New Year’s Day Stress will turn seventy, which brought back a flood of rich memories from great New Year’s Eve shows when Stress and revelers raucously marked a new year and Bill’s birthday. Alan also mentioned that when Stress was born a minute after midnight on New Year’s Day in 1943 he was feted as Cleveland’s firstborn of the new year—a fitting birth for a bluesman when you think of Muddy Waters singing about fabled characters who were ‘born the seventh son of the seventh mother on the seventh day.’ Clearly, Stress was born with an auspicious pedigree for what’s turned out to be a great life and musical career.

I will always fondly recall the many nights of fine blues and camaraderie I enjoyed thanks to Mr. Stress and the talented bandmates he played with. During the years I followed them at the Euclid Tavern his sidemen were Mike Sands, keyboard; Tim Matson, lead guitar; Ray DeForest, bass; and Nick Tranchito, drums, who Stress invariably introduced as “the Mediterranean metronome.” Living in New York City today I remain a devotee of going out to hear live music, a happy habit I began forty years ago listening to Mr. Stress. I must add that after RBC was published, Mr. Stress read my essay and we’ve been reunited via telephone and the Internet after more than 25 years being out of touch. Even with macular degeneration, he still reads voraciously with aid of voice-enabled software. We were in touch on his birthday New Year’s Day and he knows I’m presenting his story here tonight. He’s very glad to see his career remembered in Rust Belt Chic.

Philip Turner is a longtime bookseller, book editor and publisher. He lives in New York City and blogs daily at The Great Gray Bridge, where he writes about music, books, publishing, media, culture, and current affairs.

November 2012 Update: At the time I submitted the above essay for inclusion in Rust Belt Chic I had not spoken with Mr. Stress, the subject of the piece, for more than twenty-five years. Now that the book’s been published I’ve had the privilege of sharing the essay with him and being in touch once more. This has proved a real joy, truly the best benefit of having written the piece. Speaking with Stress, I learned I had made some errors in my first draft, for which I apologize. Stress has graciously helped me correct them, patching up some key gaps in my memory. One of these was the facts about the predecessor bar to the Euclid Tavern, the Brick Cottage, where Stress was regularly playing in 1972, when I first heard him. Also, I now liken him more accurately to Paul Butterfield, rather than Charlie Musselwhite, as I’d done earlier. As well, photographs not in the book are included here with the piece for the first time.

January 4 2013 Update: On January 3 in Brooklyn at a venue called Public Assembly, Rust Belt Chic was feted with readings by six contributors, and one Detroit-bred guest not in the Cleveland collection. The version of the essay posted above is pretty much as I read it last night, with some slight variations to the expanded version published on this blog in November. I’m hopeful that at some point the ebook edition of Rust Belt Chic will be updated so as to reflect the latest version of the essay. It is not dramatically different from the version published in the print edition of the book, just a bit longer. I’m grateful for your understanding.

Please click through to read the entire post and view all photos.

//more…//