Saluting Daniel Halpern, Venerable Champion of Fiction Writers

April 2 2018 Update:

Epic obituary of Drue Heinz who used her wealth to support literature incl #EccoPress (now @eccobooks) #Antaeus, etc. In 1989, an author I edited, Ellen Hunnicutt, won the Drue Heinz Literature Prize for In the Music Library. Sympathies to @Daniel_Halpern. https://t.co/zNfM0wzfcV

— Philip Turner (@philipsturner) April 2, 2018

—-

June 4, 2015

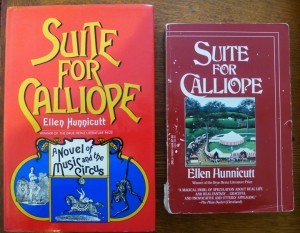

I was delighted to see Publishers Weekly reporting this afternoon that Daniel Halpern of Ecco Press is being awarded The Center for Fiction‘s annual #MaxwellPerkinsPrize for “championing writers of fiction in the United States.” I met Dan in 1987, when his stewardship at the literary magazine Antaeus brought us in to contact. The author of a book I’d edited and published, Suite for Calliope: A Novel of Music and the Circus, won the Drue Heinz Literary Prize, an award sponsored by Antaeus—a literary magazine underwritten by cultural benefactor extraordinaire Drue Heinz and edited by Dan Halpern—for a distinguished body of work in short fiction.

Ironically, I had earlier encountered the circus novel, by an as-yet unpublished writer known to me at first as E.M. Hunnicutt, when I worked as first reader/contest judge at Scribner, who in the 1980s sponsored a first novel prize in Max Perkins’s illustrious name*. Mildred Marmur, then Scribner’s president and publisher, gave me my first job in publishing, following my seven years as a bookseller.

Ironically, I had earlier encountered the circus novel, by an as-yet unpublished writer known to me at first as E.M. Hunnicutt, when I worked as first reader/contest judge at Scribner, who in the 1980s sponsored a first novel prize in Max Perkins’s illustrious name*. Mildred Marmur, then Scribner’s president and publisher, gave me my first job in publishing, following my seven years as a bookseller.

In the Scribner job, working three days every week for six weeks, my brief was to read between 5-50 pages of the more than 700 contest entries, filling out a questionnaire for each one, and recommending those I believed merited second readings. Hunnicutt’s novel was among the 70 or so I recommended (it fascinated me at the time that the number I urged for second readings was practically speaking 10% of the total. By happenstance, I wondered, or some kind of talent factor?

Hunnicutt’s manuscript was among the talented tenth I recommended for second readings, though just before job ended, I learned it wouldn’t advance further in judging. Bouyed my enjoyment of the 100 pages I had gone ahead and read, so I photocopied the title pages of the ms with the author’s contact info. A few weeks later, I got my first full-time job as an acquiring editor, at Walker & Company, I contacted Hunnicutt, who turned out to be Ellen Hunnicutt, and made her novel my first-ever fiction acquisition. Ellen had long gone by E.M. to elide her gender when submitting work to publications such as Boys’ Life. Upon my acquisition of the novel, Ellen made it clear she would now be using her proper name. Some months later, with the novel edited and in galleys, Ellen learned she was recipient of the aforementioned prize named for Drue Heinz, who I wrote about when she died in April 2018. The lead juror for the Drue Heinz Literature Prize in 1987 was Nadine Gordimer, the great South African writer, and resolute anti-apartheid campaigner. Ellen and I were very excited as her first novel headed toward publication in July that year, preceding by a few months a collection of the honored short fiction. A few months later, in an arrangement Anteus had with the University of Pittsburgh Press, Hunnicutt’s short fiction appeared as In the Music Library.

One day, back when Suite For Calliope was still in galleys, I received a printout of a starred review it got in Kirkus. The date was May 4th, and this was the review, written I learned later by Kirkus’s fiction editor at the time, Ann Larson:

An extraordinary first novel that, in its remarkable inventiveness, intelligence, and charm-struck humanity, should draw–and more than richly reward–readers of almost every inclination. Ada Cunningham, of Richmount, Indiana. is the partly crippled daughter of gifted and highly eccentric parents: a journalist mother who declares Ada to be a prodigy, raises her as such (with flamboyant Élan), then dies suddenly when her daughter is eight years old; and a father who is a musical genius, who came from poverty and was a transient violinist and artful dodger as a child, who gives Ada music lessons from the time she’s three, and who is committed to an asylum before she is 16. Life with these parents–as described by the brave, unflinching, quick, forgiving, and heartwrenchingly observant Ada–would be matter enough for many a novel, but this one soars on toward farther ends that keep the reader wide-eyed and enthralled. There’s a penetrating mystery at the heart of it all, and, before its solution: an aunt who comes into the picture with malevolent aims (she may even want to murder Ada), a burned house, legal proceedings–as result of all of which Ada, accused of being both a witch and a madwoman, flees Richmount and takes to the road (as her father did before her), supporting herself by her wits and by her gifted piano playing (in brothels and bars), until at last she finds sanctuary and refuge in the winter quarters of a circus troupe–with setting, color, and cast of characters worthy of yet another novel–where she becomes (and remains) calliope player, composer, and loved member of this wondrous new “”family.”” A summary leaves out far too much: the sturdy grace of Ada’s never-self-pitying voice; the continual feast of homely detail, and detail of music, musicians, and musical instruments, as weft as of the circus and its people; and the breathtaking symbolic depth of the whole, which, touched by the hand of this gifted writer, serves to place Ada’s birth, her flight, and her high artist’s quest among very august novelistic company indeed. A prodigiously masterful novel of profundity, breadth, and continual delight: waiting now only for what ought to be its very, very many readers.

As I learned when I called to tell Ellen the good news that her novel had received a star from the always tough Kirkus, and read the review to her (this was probably before regular use of fax machines.), I learned it was also her birthday. We had quite a celebration on the phone. (May 4th has been a meaningful date in my life on a few occasions, recollections about which I’ve collected in this post.)

When published by Walker, Suite for Calliope sold out its hardcover printing, Dell acquired the paperback rights, and it had a number of laudatory newspaper reviews. Ellen did readings in Wisconsin, near her home—Wisconsin also being the home of the notable circus museum in the town called Baraboo. Years later, when I was working at Kodansha America, and doing a few books in Buddhism, I happened to be reading the Buddhist journal, Tricycle. I came upon an interview with retired New York Knick player and NBA head coach Phil Jackson who praised Suite for Calliope as a meditative novel of ideas that he was currently recommending to friends. All in all, it was a great experience to have with the first novel I ever worked on, made all the better by Drue Heinz and Dan Halpern’s generosity toward the author. We all met in Pittsburgh in the early Spring of 1987, when Ellen received the award for her short stories. To me, it is truly fitting that Dan will receive the later iteration of the Maxwell Perkins Prize. I look forward to congratulating him in person.

To broaden the connections to my professional life even further, and take them all the way back to my roots in bookselling, when I ran Undercover Books, my bookstores in Cleveland, one of the first successful literary books we read and sold was A. Scott Berg’s biography, Maxwell Perkins: Editor of Genius, more recently a popular movie with Colin Firth as the Scribner’s Editor-in-Chief, and Jude Law as Thomas Wolfe.

* As Editor-in-Chief of Scribner in the 1920s-40s, Perkins edited and published novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, among many acclaimed authors.