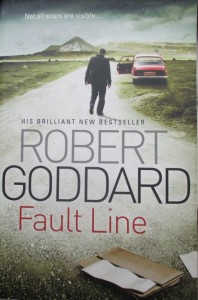

#FridayReads, July 26–British novelist Robert Goddard’s Fault Line, a totally engrossing book that weaves together a Cornwall-based ceramic company’s shrouded background with a local family’s equally buried history. Goddard is a true master of plotting, character, suspense, and surprise by whom I’ve enjoyed nearly 20 earlier books, after first discovering him in a 2008 Paste magazine feature with Stephen King, who made this unqualified endorsement of Goddard’s books:

#FridayReads, July 26–British novelist Robert Goddard’s Fault Line, a totally engrossing book that weaves together a Cornwall-based ceramic company’s shrouded background with a local family’s equally buried history. Goddard is a true master of plotting, character, suspense, and surprise by whom I’ve enjoyed nearly 20 earlier books, after first discovering him in a 2008 Paste magazine feature with Stephen King, who made this unqualified endorsement of Goddard’s books:

“The best books—yes, books—I’ve read this year are the mystery/thriller/suspense novels of a British writer named Robert Goddard. I happened on him by accident; a handful of his books have now been issued in America, but I had to get most of them direct from Britain, where he’s a bestseller. Goddard has written at an amazing pace—17 or 18 novels in as many years—but his writing is sharp and sometimes poetic. The stories, which usually center on well-kept secrets from the early part of the 20th century (in Closed Circle, the secret is a group of well-heeled British manufacturers who caused World War I) are amazing tricks of conjury. Here are surprises that really surprise. The protagonists (the books are stand-alones) are decent fellows out of their league who mostly—but not always—find a way to muddle through. These are authentic stay-up-late-to-finish stories, and there doesn’t seem to be a bad one in the bunch. The place to start is with Goddard’s first: Past Caring.”

I paid special attention to King’s recommendation owing to a personal encounter I’d had with him many years earlier. In 1979 he was already a popular novelist, with bestsellers Carrie, Salem’s Lot, and The Shining already to his name, but his books hadn’t been filmed yet or adapted for TV. Within a year or two he would be much more famous. He was on a book tour for his novel Dead Zone, probably his fifth or sixth published book, and our Viking Press sales rep brought him by my Cleveland bookstore, Undercover Books, to sign our hardcover stock of the current title, and other copies of his books we had on hand. It wasn’t a reading, just a quick drop-by.

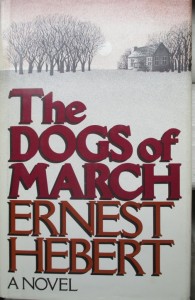

While I was gathering up our inventory, King was browsing and saw on display a copy of another then-current Viking novel. Pointing to it, he said to me and a couple customers nearby, “The really great novel from Viking right now is The Dogs of March by Ernest Hebert.” I was excited at this because I’d already read Hebert’s book, and had loved it, too. Like King from Bangor, ME, Hebert was a New Englander, from Keene, New Hampshire. The Granite State was where I had gone to college, Franconia College in the White Mountains, and I’d found Hebert’s portrayal of working class people in the North Country to be utterly real and believable. I told King that I shared his enthusiasm for Hebert’s book and that I would now recommend it to my customers all the more energetically. In fact, soon after this conversation, I wrote a letter to Hebert c/o Viking and let him know that I’d enjoyed his book, and that he and his book had booster in Stephen King and my bookstore. After, that Ernie–as I came to know him–and I carried on a correspondence for several years and I visited with him and his family on trips I made back to New Hampshire. We later fell out of touch but Hebert has continued writing novels and moved from working as a newspaper reporter to teaching English at Dartmouth, where I believe he still works. He has a number of footprints on the Internet, one via a Dartmouth url called Recycling Reality: A Writer’s View of the World and a blog of his own. From the latter, I see that The Dogs of March is officially in print 34 years after it first appeared Writing this post, I’ve decided to see if I might re-forge a connection with Hebert and so will share this post with him.

Goddard’s books are usually set in rural Britain with plots that also take his characters to such Mediterranean locales as Capri and Rhodes. Like Ross MacDonald’s Lew Archer novels, such as The Zebra Striped Hearse, which invariably chronicle multiple generations of a family and secrets that have been long buried and are excavated by private detective Archer, Goddard’s books explore the complicated histories of families that have been on the land sometimes for hundreds of years, though his books don’t feature a private detective or policeman. Instead, there’s a male narrator or protagonist who, as King says, “are decent fellows out of their league who mostly—but not always—find a way to muddle through.” In Fault Line, narrator Jonathan Kellaway is a long-time employee of the ceramics manufacturer whose corporate history is being written by an academic historian. (Like Balzac’s Lost Illusions, in which we learn about paper, ink, and printing technology in 19th century France, here we learn that Cornwall is ideal for the production of household ceramics owing to the local soil that is so rich in clay.) Kellaway’s elderly CEO details him to help the historian in her work and undertake a search for company records from a vital period of its history that have unaccountably gone missing. I’d agree the fate of a ceramics company doesn’t sound exciting, but from ordinary saplings mighty narrative oaks may grow.

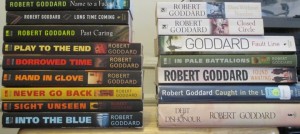

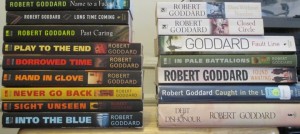

I think of Goddard as a latter-day John Fowles, the notable British novelist who produced such masterworks as The Magus and The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Along with sharing (above) a picture I took of the copy of Fault Line I finished reading yesterday, here’s a shot of all the other Goddard books I’ve read since I discovered Stephen King’s recommendation of him in early 2009.

After finishing Fault Line yesterday, I picked up a new book of literary journalism Nothin’ But Blue Skies: The Heyday, Hard Times, and Hopes of America’s Industrial Heartland by Edward McClelland. I had already read an excerpt Canoeing the Cuyahoga in the Scene, a local Cleveland magazine, and really liked his approach to writing about my old hometown. His work is full of little-known historical nuggets and on-the-ground reporting, or in this case, on-the-river reporting. McClelland is a native of Lansing, MI, so the book actually begins with some great reportage on his hometown in the 60s and 70s when auto plant culture dominated the town, with freeway ramps being designed to accommodate the auto workers’ daily arrival and exodus from the plants. Chapter One covers the Flint, MI sit-down strike of 1936-37, an event I knew nothing about until last night. As a contributor to Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology, I was glad to see that co-editor of the anthology, Anne Trubek, had enjoyed McClelland’s book and is quoted about it on the back cover: “McClelland assembles old-school reporting, memoir, history, and wit into a brilliant story about the workers and robber barons who created booming economies, the strikes, politics, and global changes that rendered them depressed, and the people from Decatur to Syracuse trying to figure out what’s next. Neither starry-eyed nor despairing, Nothin’ But Blue Skies is the book to read on the past, present, and future of the Rust Belt.”

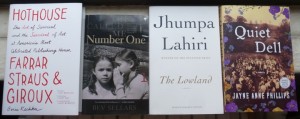

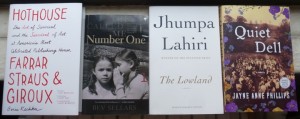

No question it’s been a great past week of reading. And it’s going to be a great few more weeks of reading to come with such books in my to-be-read pile as They Called Me Number One: Secrets and Survival at a Residential Indian School by Bev Sellars, Chief of the Soda Creek First Nation band of British Columbia, Canada; Boris Kaschka’s Hothouse: The Art of Survival and the Survival of Art at America’s Most Celebrated Publishing House; Jumpa Lahiri’s September novel, The Lowland; and Jayne Anne Phillips’ October novel, Quiet Dell.

Please note: All the book links in this blog post are live and go to the website of Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon. Under an arrangement I’ve made with Powell’s, if you choose to buy any books linked, they return a portion of your purchase price to help me maintain this website.

Last summer I wrote a #FridayReads essay that recalled a 1979 visit to my bookstore Undercover Books by a young novelist named Stephen King–then only in the early years of what would become his decades-long career as a bestselling novelist. While discussing his new book Dead Zone he excitedly recommended to me a novel from his publisher, The Dogs of March by Ernest Hebert. I eagerly told King that I had already read Hebert’s book and that I would from then on tell my customers about his endorsement of it, and recommend it even more energetically. Soon after King’s visit to my bookstore, I wrote a letter to Hebert c/o his editor, the late and much-missed Alan Williams at the Viking Press (who was also King’s editor then). I let Hebert know that I’d enjoyed The Dogs of March, and that he and his novel had boosters in Stephen King and at my bookstore. After, that Ernie, as I came to know him, and I carried on a correspondence that continued for several years. I also visited him and his family on trips I made from Cleveland back to New Hampshire, where I had attended Franconia College earlier in the ’70s. One of the things that Ernie did with great skill in The Dogs of March was to juxtapose longtime residents in New England towns with incomers, or as he puts it, “natives vs. newcomers.” He wrote compelling fiction about all kinds of characters, and did it with a sharp edge of social observation.

Last summer I wrote a #FridayReads essay that recalled a 1979 visit to my bookstore Undercover Books by a young novelist named Stephen King–then only in the early years of what would become his decades-long career as a bestselling novelist. While discussing his new book Dead Zone he excitedly recommended to me a novel from his publisher, The Dogs of March by Ernest Hebert. I eagerly told King that I had already read Hebert’s book and that I would from then on tell my customers about his endorsement of it, and recommend it even more energetically. Soon after King’s visit to my bookstore, I wrote a letter to Hebert c/o his editor, the late and much-missed Alan Williams at the Viking Press (who was also King’s editor then). I let Hebert know that I’d enjoyed The Dogs of March, and that he and his novel had boosters in Stephen King and at my bookstore. After, that Ernie, as I came to know him, and I carried on a correspondence that continued for several years. I also visited him and his family on trips I made from Cleveland back to New Hampshire, where I had attended Franconia College earlier in the ’70s. One of the things that Ernie did with great skill in The Dogs of March was to juxtapose longtime residents in New England towns with incomers, or as he puts it, “natives vs. newcomers.” He wrote compelling fiction about all kinds of characters, and did it with a sharp edge of social observation.