Powerful Endorsements for “Devouring Time: Jim Harrison, a Writer’s Life” by Todd Goddard

Along with all the terrific endorsements the author and publisher have received for Devouring Time: Jim Harrison, a Writer’s Life by our agency client Todd Goddard (shown below), we now also have an enthusiastic Publishers Weekly review (“A perceptive account of a prolific and celebrated artist.”), which was quickly shared by the proprietor of the popular Jim Harrison Author Page on Facebook**, where it’s generating more enthusiasm and pre-orders ahead of the book’s launch on November 4.

—-

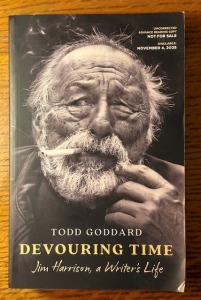

As announced previously on this website, Devouring Time: Jim Harrison, a Writer’s Life by our agency client Todd Goddard, the first biography of the notable American author, will be published on November 4, 2025, in hardcover, audiobook, and ebook by Blackstone Publishing. The book has garnered powerful endorsements so far, from writers Gretel Ehrlich, Rebecca Solnit, Colum McCann, Carl Hiassen, John Matteson, William Souder, and Jim Fergus, as shown below.

If you’re interested in pre-ordering the book, here are links for doing so:

Bookshop.org (Bookshop is an online bookseller whose sales support independent bookstores), 2) Barnes & Noble, 3) Books-A-Million, and 4) Amazon.

—

Advance Praise for Devouring Time: Jim Harrison, a Writer’s Life by Todd Goddard

“Devouring Time is a massive achievement, a deep plunge into the life of Jim Harrison whose 40 books of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry line our shelves. Atavistic, inspired, despairing, gluttonous, turbo-charged, and broken-hearted, the gut strings of what drove Harrison are plucked, page by page until his high-wire obsessions, his “beggar’s banquets” of eating, drinking, traveling, and writing finally recede. What lasts are the words.”—Gretel Ehrlich, author of The Solace of Open Spaces and Unsolaced: Along the Way to All That Is

“Jim Harrison was a mustang that never got corralled, or at least broke out of all the paddocks he found himself in, and Todd Goddard tells the story of this bon vivant, outdoorsman, hellion, and great poet from his ancestors to his end with grace, momentum, generosity, and insight. I was more than glad to go on the journey that was Harrison’s life in Devouring Time’s narrative, and what a great American life it was, wreckage, glory, gifts, and all.”—Rebecca Solnit, author of Orwell’s Roses

“Jim Harrison is and always will be one of my great heroes. He emerges from Todd Goddard’s splendid Devouring Time in vivid technicolor, and indeed shadow, as if he could walk off the page at any moment, sounding out his American yawp. Gracefully rendered and impeccably researched, Goddard intimately charts the free-flowing river that was Harrison’s life, its headwaters and tributaries, the glistening shallows and eddies, and the dark charging currents that carved channels through the literary landscape. His timeless poetry and fiction, singular joie de vivre, boundless appetites and intellect, as well as his unerring commitment to wisdom and wildness, resound on every page. One of our most cherished writers, Jim Harrison has landed in the hands of a worthy biographer. An absolute pleasure to read, Devouring Time resonates with me still.”—Colum McCann, author of Let the Great World Spin and Apeirogon

“My friend Jim Harrison always seemed a fiercely untameable subject for a biographer, but I think Devouring Time will stand as a complete and moving portrait. Jim was one of those rare writers whose private life was as adventurous as their works, but only a dogged journalist could have tracked down all the tales. Todd Goddard tells the whole story in a way that Jim would have admired – raw and revealing, yet with a sensitive eye for both the pain and the talent that made Jim one of modern America’s most intriguing poets and novelists.”—Carl Hiaasen, author of Bad Monkey and Fever Beach

“Jim Harrison lived a big life, and he has long deserved a gargantuan biography, both in size and spirit. And this is what Todd Goddard has given us. All by itself, the meticulously rendered story of how Harrison’s prose masterpiece Legends of the Fall came into being would be ample reward for the curious reader. But Goddard has given us immeasurably more. Impeccably researched, sensitively written, Devouring Time gives us a man — one who experienced the very depths of pain but found there the building blocks of enduring art. Cruelly battered by adversity, Harrison nevertheless infused his world with transcendent song. Read in conjunction with his own work, Devouring Time completes his testament.”—John Matteson, Pulitzer-Prize-winning author of Eden’s Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father

“A feast of a biography that does full justice to a writer whose vast appetites…for books, food, sex, success, and a life in the wild…fueled a prodigious and prolific talent. Sweeping yet judicious, written with grace and restraint, Devouring Time deftly captures a life that veered between exhilaration and despair, impoverishment and acclaim. A keen-eyed and sensitive interpreter of Harrison’s writing, especially his poetry, Todd Goddard also grapples with his subject’s manifold excesses and insecurities. Harrison’s long marriage to his wife Linda, to whom he was serially unfaithful but never faithless, anchored his tempestuous personality. Their often-challenged devotion to each other is the beating heart of this moving portrayal of an artist who craved domesticity but could never live entirely within its boundaries. An exquisite, indelible book.”—William Souder, author of Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck

“Let me just say upfront that any other writers who are working on, and/or planning to write a biography about the life and times of poet/novelist Jim Harrison, I would suggest that you hang up your pens and pencils, fold up your laptops, and turn your literary attentions elsewhere. Todd Goddard here delivers the most definitive possible such work, a book brilliantly constructed, comprehensive and artfully written.

I was a close friend of Jim Harrison’s for thirty-seven years (among, of course, many others) right up until the evening of his death. I thought in that time (as many of us did) that I had heard virtually all of Jim’s stories, some more than once, for he was a consummate storyteller, frequently with alternate versions of his tales, and never too shy to talk about himself.

Herein are the rich details of the life and career of one of America’s sometimes overlooked literary geniuses, a man devoted to his art, who pushed his talents, and body, to the limit, from the rarefied world of poetry, to fiction and novels, to screenplays on the other end of the spectrum. Along the way, the reader will learn a great deal about the complicated and sometimes cutthroat literary and film businesses, as well as meet a vast array of friends, family members and colleagues who peopled Jim’s world.

There are no punches pulled here; like so many creative geniuses, Jim Harrison had his dark side, fueled by alcoholism of which he himself was more than well aware. This is a big book, and not just in size, that tells the story of an extraordinary character unlike any other, a man so totally out of the ordinary, that those of us who knew him personally, forgive him all his excesses, remember his humor and generosity, and will miss his presence on earth until the day we die.”—Jim Fergus, author of One Thousand White Women: The Journals of May Dodd

**