Books I’ve brought out as publisher; essays and reviews I’ve published

Appreciative for a Shoutout to My Editing of “The Revenant” from Canadian Pal Grant Lawrence

/0 Comments/in Art, Film, TV, Photography, Fine Printing & Design, Books & Writing, Philip Turner's Books & Writing /by Philip TurnerI'm tickled that Canadian music journalist, CBC broadcaster, author, friend—and devoted reader of adventure tales—Grant… Posted by Philip Turner on Wednesday, 23 March 2016

Did the Koch Brothers’ Help Dad Build an Oil Refinery for Adolf Hitler?

/0 Comments/in Books & Writing, News, Politics, History & Media, Philip Turner's Books & Writing /by Philip Turner Wow, this is going to be a blockbuster book. Jane Mayer’s latest, due out Jan 19th, is Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right. It’s the subject of a NY Times news article tonight by Nicholas Confessore who must’ve gotten an early copy. He reports on the collective portrait of rightwing billionaire families, including Richard Mellon Scaife, who before his death in 2014 spent more than a billion dollars of his Mellon family fortune pushing conservative causes; most notably, in the 1990s he harassed Bill Clinton through the infamous American Spectator magazine (see “Troopergate” if you need a reminder). I recall of this with firsthand memory because in the early 2000s I edited and published Susan MacDougal’s memoir of the years she was pursued by Whitewater Special Prosecutor Kenneth Starr, The Woman Who Wouldn’t Talk: Why I Wouldn’t Testify the Clintons and What I Learned in Jail., whose probe was an outgrowth of Scaife’s bankrolling Whitewater into a faux scandal. After discussing Scaife, the book examines an earlier brother pair, Lynde and Harry Bradley; and the DeVos family of Michigan. Apparently, Mayer then moves on to the bulk of her book, the Koch family. Confessore releases this explosive finding from Mayer’s investigation:

Wow, this is going to be a blockbuster book. Jane Mayer’s latest, due out Jan 19th, is Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right. It’s the subject of a NY Times news article tonight by Nicholas Confessore who must’ve gotten an early copy. He reports on the collective portrait of rightwing billionaire families, including Richard Mellon Scaife, who before his death in 2014 spent more than a billion dollars of his Mellon family fortune pushing conservative causes; most notably, in the 1990s he harassed Bill Clinton through the infamous American Spectator magazine (see “Troopergate” if you need a reminder). I recall of this with firsthand memory because in the early 2000s I edited and published Susan MacDougal’s memoir of the years she was pursued by Whitewater Special Prosecutor Kenneth Starr, The Woman Who Wouldn’t Talk: Why I Wouldn’t Testify the Clintons and What I Learned in Jail., whose probe was an outgrowth of Scaife’s bankrolling Whitewater into a faux scandal. After discussing Scaife, the book examines an earlier brother pair, Lynde and Harry Bradley; and the DeVos family of Michigan. Apparently, Mayer then moves on to the bulk of her book, the Koch family. Confessore releases this explosive finding from Mayer’s investigation:

“The book is largely focused on the Koch family, stretching back to its involvement in the far-right John Birch Society and the political and business activities of their father, Fred C. Koch, who found some of his earliest business success overseas in the years leading up to World War II. One venture was a partnership with the American Nazi sympathizer William Rhodes Davis, who, according to Ms. Mayer, hired Mr. Koch to help build the third-largest oil refinery in the Third Reich, a critical industrial cog in Hitler’s war machine.”

As editor, I also acquired IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation (2001, Crown Publishing) by Edwin Black, and on this website blogged several times about The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler by Ben Urwand. I have an eye for these sort of titles, and I’m sure this one by Mayer will be fascinating, and important.

As editor, I also acquired IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation (2001, Crown Publishing) by Edwin Black, and on this website blogged several times about The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler by Ben Urwand. I have an eye for these sort of titles, and I’m sure this one by Mayer will be fascinating, and important.

Holiday Reflections

/0 Comments/in Books & Writing, Philip Turner's Books & Writing /by Philip TurnerLater today my wife and I will be going to visit Ruth Gruber, the pioneering female photojournalist and longtime author…

Posted by Philip Turner on Friday, 25 December 2015

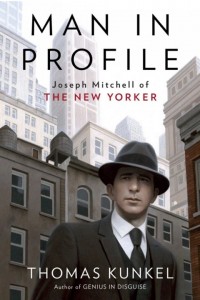

Appreciating Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker, and the Legacy of his Writing

/0 Comments/in Books & Writing, Philip Turner's Books & Writing, Urban Life & New York City /by Philip Turner I spent the past couple weeks, amid so much disturbing upheaval in the world outside my reading, deeply enjoying Man in Profile: Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker, by Thomas Kunkel, which Random House published last June. (I had first shared about it on this blog last May.) From Kunkel’s acknowledgments at the end I’ve learned the book was commissioned by Bob Loomis*, the great editor there who, before his retirement in 2012, signed up the book, though the manuscript was evidently delivered after his departure. Mitchell grew up in a tobacco- and cotton-farming family in North Carolina (b. 1908) and, disappointing his father, moved to New York City at twenty-one, determined to become a newspaperman, even amid the Depression; he found work as a copy boy, and soon began reporting and writing, including at the Herald Tribune (where my longtime author, photojournalist Ruth Gruber later worked) and for the World-Telegram, which Mitchell joined in 1930. He began writing for The New Yorker in 1932, and joined the magazine’s staff in 1938. Kunkel’s book is a superb portrait of Mitchell’s whole life, to his death in 1996, and a rich appreciation of his writings.

I spent the past couple weeks, amid so much disturbing upheaval in the world outside my reading, deeply enjoying Man in Profile: Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker, by Thomas Kunkel, which Random House published last June. (I had first shared about it on this blog last May.) From Kunkel’s acknowledgments at the end I’ve learned the book was commissioned by Bob Loomis*, the great editor there who, before his retirement in 2012, signed up the book, though the manuscript was evidently delivered after his departure. Mitchell grew up in a tobacco- and cotton-farming family in North Carolina (b. 1908) and, disappointing his father, moved to New York City at twenty-one, determined to become a newspaperman, even amid the Depression; he found work as a copy boy, and soon began reporting and writing, including at the Herald Tribune (where my longtime author, photojournalist Ruth Gruber later worked) and for the World-Telegram, which Mitchell joined in 1930. He began writing for The New Yorker in 1932, and joined the magazine’s staff in 1938. Kunkel’s book is a superb portrait of Mitchell’s whole life, to his death in 1996, and a rich appreciation of his writings.

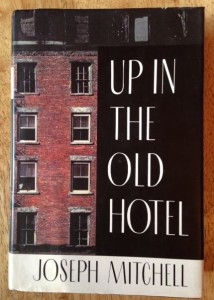

While reading and really savoring the whole book, every anecdote, every chapter it covers of Mitchell’s life, I took down from a bookshelf my copy of Up in the Old Hotel, the 1992 collection that gathered Mitchell’s profiles on true-life New York characters, and other work, which back then put Mitchell back on the map for many readers. Until then, his magazine pieces had frequently been gathered up and published between hardcovers—his first My Ears Are Bent, came out in 1938, followed by McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon (1943); Old Mr. Flood (1948); The Bottom of the Harbor (1959) and Joe Gould’s Secret (1965)—but it was more than two decades between books when, at the urging of Dan Frank of Pantheon Books, Mitchell published this full omnibus of his work, gathered from those books, and other sources. It made a big splash at the time, getting stellar reviews, and Kunkel tells us that Mitchell welcomed the spotlight that came with being remembered by so many readers, and discovered by even more.

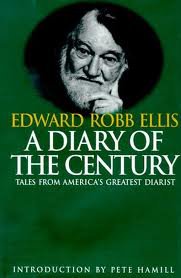

I’ve had the book since soon after it came out—my copy’s a first edition. I was around that time editing and preparing to publish a comparable book, A Diary of Century: Tales from America’s Greatest Diarist, by Edward Robb Ellis, a near-contemporary of Mitchell’s, who also worked at the World-Telegram, arriving there in 1947. Like Mitchell, Ellis savored writing about memorable NY characters, people like Fred Bronnenkant, riveter for more than thirty years on the Brooklyn Bridge, who had such affection for the span he regarded it as a kind of mistress**. Though Eddie was not quite the consummate stylist that I now see Mitchell was, like Mitchell, he aspired to make great work. Both men learned writing in the same milieu—the midcentury American newspaper, entirely at NY papers for Mitchell, partly true for Ellis, who before coming to the metropolis to work at the World-Telegram (which in the 1950s tagged itself as “NY’s most ebullient newspaper”), had worked at papers in New Orleans, Oklahoma City, Peoria, and Chicago.*** They deployed vivid imagery, showed a fondness for lengthy list-making (a penchant embraced in more recent years by New Yorker writer John McPhee), a keen interest in what things cost back in the day, and an appreciation for character, with great skill at presenting to readers the people they encountered.

Seeing the success of Up in the Old Hotel, I recalling buying the book in hopes of imbibing some of that vibe and investing Eddie’s book with it. Though I was interested in Mitchell and his work, as happens for professional editors, I got sidetracked from it, and had in fact never read it thoroughly, nor really sensed the charms of Mitchell’s writing until the past couple weeks. During the weeks I was reading the Kunkel bio, I also leafed through the 700+page anthology, shown here, and now that I’ve finished the biography, I’m fully able to dive in to it. Last night, I read and enjoyed the third Profile in the anthology, about Mazie Gordon, a denizen of the Bowery, who ran a “moving-picture house” called the Venice Theatre, about whom “Detective Kain [of the Oak Street police station] says that she has the roughest tongue and the softest heart in the Third Precinct.” Mitchell chronicles her working life, seated in a glassed-in booth along Park Row, selling movie tickets, and greeting her patrons, some of whom are by her own description “bums” that live in nearby flophouses. She is a key player in the street life near Chatham Square, and the piece includes many conversations she had with bums, cops, priests, and all kinds of urban operators which it seems certain Mitchell overheard. His chronicle of Mazie’s proprietorship of the theatre, and her status in the wider neighborhood, is among the most enjoyable things I’ve read this year.

Here’s the first paragraph of the 1940 profile, titled ‘Mazie’:

“A bossy, yellow-haired blonde named Mazie P. Gordon is a celebrity on the Bowery in the nickel-a-drink saloons and in the all-night restaurants which specialize in pig snouts and cabbage at a dime a platter, she is known by her first name. She makes a round of these establishments practically every night, and drunken bums sometimes come up behind her, slap her on the back, and call her sweetheart. This never annoys her. She has a wry but genuine fondness for bums and is undoubtedly acquainted with more of them than any person in the city. Each day she gives them between five and fifteen dollars in small change….’In my time, I’ve been as free with my dimes as old John D himself,’ she says. Mazie has presided for twenty-one years over the ticket cage of the Venice Theatre.”

Now that I’m finished with the biography, I’ve also sought out reviews of it, such as a good one by John Williams in the NY Times, and a very insightful essay by Janet Malcolm in the NY Review of Books; she was a colleague of Mitchell’s at The New Yorker. Kunkel wrote an earlier biography of Harold Ross, founding editor of The New Yorker, who hired Mitchell for the magazine, after his several-year audition as a contributing writer. I’ve never met Kunkel, but I’m glad to say I feel connected to him anyway. As it happens, he reviewed Edward Robb Ellis’s A Diary of Century when it was published in 1995, with an Introduction by Pete Hamill, concluding his review in the Washington Post with the praise that Ellis’s diary of an Everyman, “produc[ed] something akin to Copland’s glorious ‘Fanfare for the Common Man.'” I’ll find a way to share this blog post with him, so I can belatedly let him know how glad I am that he enjoyed Eddie Ellis’s book, and I can tell him I felt the same for his superb book on Joseph Mitchell.

—

* Among Bob Loomis’s authors was William Styron; the courtly editor helped me enlist Styron’s aid in a championing a book I edited in 1999, about an arguably innocent inmate on Virginia’s Death Row. I wrote about that episode in my editorial career in an essay for the BN Review called “William Styron: A Promise Kept.”

**Ellis’s beguiling entry on Frank Bronnenkant is found on pgs 173-75 of A Diary of the Century (Kodansha America, 1995; republished by me at Union Square Press in 2008). Clicking on this link will take you to all my blog posts about Edward Robb Ellis, which includes one that examines the legacy of notorious faker Joe Gould, the subject of Mitchell’s last published profile; the recently discovered photographer, Vivian Maier; and Ellis, in a 2014 piece I titled “Vivian Maier Was the Real Deal, the Ultra-Opposite of Joe Gould.” The relevance here is that Ellis—whose book was drawn from his diary, a journal he began keeping at age 16, and which he stayed with until the year of his death at 89, the longest-kept such record in the history of American letters—and the secretly great and prolific street photographer Maier did each create a magnum opus, while Gould never did, though Mitchell did believe for a time that Gould really was writing a seminal work, “The Oral History of our Times.” And yet Mitchell, even after publishing two long profiles of Gould (‘Professor Seagull,’ ’42, rather credulous) and (‘Joe Gould’s Secret,’ ’64, not credulous any longer) did not rebuke Gould. He generously concluded that Gould, some writings by whom he had actually read in the 1940s, had perhaps at least been writing in his mind, as Mitchell did with an uncompleted memoir and novel he never published. I see a tragedy in that for Mitchell, but also kind of a decent-hearted triumph.

*** For her part, Ruth Gruber, before and after WWII, wrote for the Herald Tribune and the NY Post. Unlike Mitchell and Ellis, she oscillated in and out of journalism, working for a time in the federal government during the FDR Administration, as Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes’ special representative to Alaska from 1940-46. Ruth is, so far as I know, the eldest surviving member of the Franklin Roosevelt Administration. This post is about a 104th birthday gathering with her this past October.

Saluting Daniel Halpern, Venerable Champion of Fiction Writers

/0 Comments/in Book Biz, Books & Writing, Philip Turner's Books & Writing /by Philip TurnerApril 2 2018 Update:

Epic obituary of Drue Heinz who used her wealth to support literature incl #EccoPress (now @eccobooks) #Antaeus, etc. In 1989, an author I edited, Ellen Hunnicutt, won the Drue Heinz Literature Prize for In the Music Library. Sympathies to @Daniel_Halpern. https://t.co/zNfM0wzfcV

— Philip Turner (@philipsturner) April 2, 2018

—-

June 4, 2015

I was delighted to see Publishers Weekly reporting this afternoon that Daniel Halpern of Ecco Press is being awarded The Center for Fiction‘s annual #MaxwellPerkinsPrize for “championing writers of fiction in the United States.” I met Dan in 1987, when his stewardship at the literary magazine Antaeus brought us in to contact. The author of a book I’d edited and published, Suite for Calliope: A Novel of Music and the Circus, won the Drue Heinz Literary Prize, an award sponsored by Antaeus—a literary magazine underwritten by cultural benefactor extraordinaire Drue Heinz and edited by Dan Halpern—for a distinguished body of work in short fiction.

Ironically, I had earlier encountered the circus novel, by an as-yet unpublished writer known to me at first as E.M. Hunnicutt, when I worked as first reader/contest judge at Scribner, who in the 1980s sponsored a first novel prize in Max Perkins’s illustrious name*. Mildred Marmur, then Scribner’s president and publisher, gave me my first job in publishing, following my seven years as a bookseller.

Ironically, I had earlier encountered the circus novel, by an as-yet unpublished writer known to me at first as E.M. Hunnicutt, when I worked as first reader/contest judge at Scribner, who in the 1980s sponsored a first novel prize in Max Perkins’s illustrious name*. Mildred Marmur, then Scribner’s president and publisher, gave me my first job in publishing, following my seven years as a bookseller.

In the Scribner job, working three days every week for six weeks, my brief was to read between 5-50 pages of the more than 700 contest entries, filling out a questionnaire for each one, and recommending those I believed merited second readings. Hunnicutt’s novel was among the 70 or so I recommended (it fascinated me at the time that the number I urged for second readings was practically speaking 10% of the total. By happenstance, I wondered, or some kind of talent factor?

Hunnicutt’s manuscript was among the talented tenth I recommended for second readings, though just before job ended, I learned it wouldn’t advance further in judging. Bouyed my enjoyment of the 100 pages I had gone ahead and read, so I photocopied the title pages of the ms with the author’s contact info. A few weeks later, I got my first full-time job as an acquiring editor, at Walker & Company, I contacted Hunnicutt, who turned out to be Ellen Hunnicutt, and made her novel my first-ever fiction acquisition. Ellen had long gone by E.M. to elide her gender when submitting work to publications such as Boys’ Life. Upon my acquisition of the novel, Ellen made it clear she would now be using her proper name. Some months later, with the novel edited and in galleys, Ellen learned she was recipient of the aforementioned prize named for Drue Heinz, who I wrote about when she died in April 2018. The lead juror for the Drue Heinz Literature Prize in 1987 was Nadine Gordimer, the great South African writer, and resolute anti-apartheid campaigner. Ellen and I were very excited as her first novel headed toward publication in July that year, preceding by a few months a collection of the honored short fiction. A few months later, in an arrangement Anteus had with the University of Pittsburgh Press, Hunnicutt’s short fiction appeared as In the Music Library.

One day, back when Suite For Calliope was still in galleys, I received a printout of a starred review it got in Kirkus. The date was May 4th, and this was the review, written I learned later by Kirkus’s fiction editor at the time, Ann Larson:

An extraordinary first novel that, in its remarkable inventiveness, intelligence, and charm-struck humanity, should draw–and more than richly reward–readers of almost every inclination. Ada Cunningham, of Richmount, Indiana. is the partly crippled daughter of gifted and highly eccentric parents: a journalist mother who declares Ada to be a prodigy, raises her as such (with flamboyant Élan), then dies suddenly when her daughter is eight years old; and a father who is a musical genius, who came from poverty and was a transient violinist and artful dodger as a child, who gives Ada music lessons from the time she’s three, and who is committed to an asylum before she is 16. Life with these parents–as described by the brave, unflinching, quick, forgiving, and heartwrenchingly observant Ada–would be matter enough for many a novel, but this one soars on toward farther ends that keep the reader wide-eyed and enthralled. There’s a penetrating mystery at the heart of it all, and, before its solution: an aunt who comes into the picture with malevolent aims (she may even want to murder Ada), a burned house, legal proceedings–as result of all of which Ada, accused of being both a witch and a madwoman, flees Richmount and takes to the road (as her father did before her), supporting herself by her wits and by her gifted piano playing (in brothels and bars), until at last she finds sanctuary and refuge in the winter quarters of a circus troupe–with setting, color, and cast of characters worthy of yet another novel–where she becomes (and remains) calliope player, composer, and loved member of this wondrous new “”family.”” A summary leaves out far too much: the sturdy grace of Ada’s never-self-pitying voice; the continual feast of homely detail, and detail of music, musicians, and musical instruments, as weft as of the circus and its people; and the breathtaking symbolic depth of the whole, which, touched by the hand of this gifted writer, serves to place Ada’s birth, her flight, and her high artist’s quest among very august novelistic company indeed. A prodigiously masterful novel of profundity, breadth, and continual delight: waiting now only for what ought to be its very, very many readers.

As I learned when I called to tell Ellen the good news that her novel had received a star from the always tough Kirkus, and read the review to her (this was probably before regular use of fax machines.), I learned it was also her birthday. We had quite a celebration on the phone. (May 4th has been a meaningful date in my life on a few occasions, recollections about which I’ve collected in this post.)

When published by Walker, Suite for Calliope sold out its hardcover printing, Dell acquired the paperback rights, and it had a number of laudatory newspaper reviews. Ellen did readings in Wisconsin, near her home—Wisconsin also being the home of the notable circus museum in the town called Baraboo. Years later, when I was working at Kodansha America, and doing a few books in Buddhism, I happened to be reading the Buddhist journal, Tricycle. I came upon an interview with retired New York Knick player and NBA head coach Phil Jackson who praised Suite for Calliope as a meditative novel of ideas that he was currently recommending to friends. All in all, it was a great experience to have with the first novel I ever worked on, made all the better by Drue Heinz and Dan Halpern’s generosity toward the author. We all met in Pittsburgh in the early Spring of 1987, when Ellen received the award for her short stories. To me, it is truly fitting that Dan will receive the later iteration of the Maxwell Perkins Prize. I look forward to congratulating him in person.

To broaden the connections to my professional life even further, and take them all the way back to my roots in bookselling, when I ran Undercover Books, my bookstores in Cleveland, one of the first successful literary books we read and sold was A. Scott Berg’s biography, Maxwell Perkins: Editor of Genius, more recently a popular movie with Colin Firth as the Scribner’s Editor-in-Chief, and Jude Law as Thomas Wolfe.

* As Editor-in-Chief of Scribner in the 1920s-40s, Perkins edited and published novels by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, among many acclaimed authors.

Eager to Participate in the Adirondack Center for Writing’s Publishing Conference, June 6-7

/0 Comments/in Book Biz, Philip Turner's Books & Writing /by Philip TurnerI’m looking forward to being part of the Adirondack Center for Writing’s Publishing Conference on Sunday June 7. I will be evaluating the work of about a dozen writers during the workshop. It should be fun to encounter all this new work and talk about writing and publishing with all the participants. The conference will be held near Lake Placid, NY. If you know any writers who live in that region of upstate NY, please let them know about the event. Thanks to Michael Coffey and Nathalie Costa for the invitation. Click here for more details and see the screenshot below.

Tracking Malaria, its Calamitous History and Worrying Future

/0 Comments/in Book Biz, Philip Turner's Books & Writing, Publishing & Bookselling, Science /by Philip Turner Fascinating Q&A on C-Span BookTV w/narrative science writer Karen Masterson, author of The Malaria Project: The US Government’s Secret Mission to Find a Miracle Cure, which chronicles the efforts of the US military which had for long been worried about the disease’s potential to infect American troops serving in far-flung locales. There was a move to find a cure for the mosquito-borne disease. Interesting to me, the book, which looks to be fairly serious science, is published by NAL. They brought out it in 2014, apparently first in hardcover. By my reckoning, NAL is a house long known more for mass-market paperback fiction than narrative nonfiction in hardcover. [It looks like they’ve now brought it out now in trade paperback.] Good for NAL, a nice piece of publishing. More on Masterson and her book via this link. You can view the video via this link on BookTV’s website.

Fascinating Q&A on C-Span BookTV w/narrative science writer Karen Masterson, author of The Malaria Project: The US Government’s Secret Mission to Find a Miracle Cure, which chronicles the efforts of the US military which had for long been worried about the disease’s potential to infect American troops serving in far-flung locales. There was a move to find a cure for the mosquito-borne disease. Interesting to me, the book, which looks to be fairly serious science, is published by NAL. They brought out it in 2014, apparently first in hardcover. By my reckoning, NAL is a house long known more for mass-market paperback fiction than narrative nonfiction in hardcover. [It looks like they’ve now brought it out now in trade paperback.] Good for NAL, a nice piece of publishing. More on Masterson and her book via this link. You can view the video via this link on BookTV’s website.

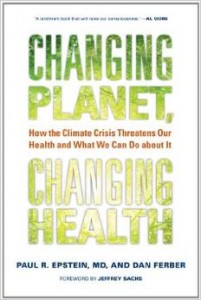

One thing Masterson said amazed me. The effectiveness of bed nets—which have been a useful tool in combating malaria, preventing mosquitoes from biting people while they sleep—is being eroded because mosquitoes, hungry for what scientists call their “blood meal,” are adapting their behavior and learning to bite people earlier in the day when they are still out and about. In watching her talk about this global affliction that still sickens and weakens millions worldwide every year—and kills a considerable percentage of those stricken—I was reminded of a book that I began discussing in 2006 with Paul R. Epstein—a doctor and scientist, and at the time, associate director of Harvard’s Center for Health and the Global Environment. Epstein was a trailblazer in studying the effects of climate change on human health. I first heard his distinctive New York accent when he was a guest that year on an episode of “Fresh Air” with Terry Gross. You can still hear it, via this link. Listening to their conversation in a rental car, in a classic ‘driveway moment,’ I learned that due to the planet’s warming temperatures, mosquitoes that transmit malaria have over the past several decades begun doing so at more northern latitudes and higher elevations than they have ever been known to do before. Epstein also discussed the finding that the tick-borne illness dengue fever is also occurring at latitudes and elevations where it was before not seen. Epstein discussed how these diseases are infecting a much greater number of people worldwide due to the warming of our planet.

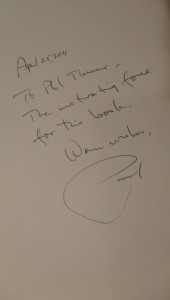

These are only a couple of the scientific discoveries chronicled in Epstein’s book, Changing Planet, Changing Health: How the Climate Crisis Threatens Our Health and What We Can Do about It, co-written with Dan Ferber, which ultimately came out in 2011. I actually commissioned it in 2007, shortly after I became Editorial Director of Union Square Press at Sterling Publishing, a job that ended two years later when Sterling, a division of Barnes & Noble, shuttered the imprint, a milestone I’ve also written about on this blog. When I left the company, my old bosses quickly canceled Dr. Epstein’s book, although I had nearly completed editing the manuscript. Fortunately, that decision, though very shortsighted, while preventing the book from being published as soon as it might have, it was later picked up by the University of California Press, to be published alongside other important environmental titles. This is a link to the book on U Cal’s website. Sadly, Dr. Epstein, died in November 2011, at age 67, of cancer. Here’s a Washington Post obit on him. Though we fell out of touch after Union Square Press closed, I recall we did speak a couple more times, and he sent me a finished copy of the book, which he inscribed to me with a very generous message, “April 25, 2011 To Phil Turner—The motivating force for this book. Warm wishes, Paul,” pictured below. I didn’t know he was ill, and was stunned by news of his death.

Before Dr. Epstein became a teacher and researcher at Harvard, he had worked as a doctor in places like Mozambique and Angola, devoting himself to the study of tropical diseases and improving public health in developing countries. It was a privilege to meet and work with him. I was really sorry he wasn’t able to make personal appearances in front of audiences, on TV, and on radio, like I first heard him. As I listened to Karen Masterson on C-Span tonight, I found myself wondering if she knows about Paul’s research on the growing incidence of malaria and other illnesses worldwide due to climate change, and if she has perhaps read Dr. Epstein’s book. I see she teaches science writing at Johns Hopkins, so perhaps I’ll have a chance to send her this post and find out. [I did correspond with Ms Masterson and she was interested to learn about Dr Epstein and his book.]

Before Dr. Epstein became a teacher and researcher at Harvard, he had worked as a doctor in places like Mozambique and Angola, devoting himself to the study of tropical diseases and improving public health in developing countries. It was a privilege to meet and work with him. I was really sorry he wasn’t able to make personal appearances in front of audiences, on TV, and on radio, like I first heard him. As I listened to Karen Masterson on C-Span tonight, I found myself wondering if she knows about Paul’s research on the growing incidence of malaria and other illnesses worldwide due to climate change, and if she has perhaps read Dr. Epstein’s book. I see she teaches science writing at Johns Hopkins, so perhaps I’ll have a chance to send her this post and find out. [I did correspond with Ms Masterson and she was interested to learn about Dr Epstein and his book.]