Remembering a Vanished World

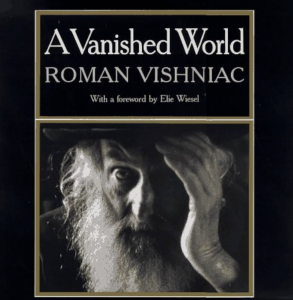

Excellent review/essay about a new documentary on the photography and the life of Roman Vishniac (1897-1990), the foremost chronicler of Eastern European Jewry. Vishniac’s major book A Vanished World (FSG, 1983) is a touchstone volume; though it was an oversized hardcover, coffee-table style book—with dozens of richly printed full-page images which sold for at least $50 when it came out—in my Cleveland bookstore, Undercover Books, we ordered lots of copies, stacked it up, and sold dozens. The essay is by Mark Athitakis, a critic whose reviews I alway enjoy. He explains that Vishniac, who was born in Russia, not Eastern Europe, had scientific training, and after narrowly saving himself and his family from the Nazis, and coming to America in 1940, “he taught biology and photography at New York colleges and, in the ’50s and ’60s gained fame for his microphotography—high-resolution shots of live insects and colorful images of amoebas and protozoa and human tissue filled the pages of magazines such as Life and Boys’ Life.”

Excellent review/essay about a new documentary on the photography and the life of Roman Vishniac (1897-1990), the foremost chronicler of Eastern European Jewry. Vishniac’s major book A Vanished World (FSG, 1983) is a touchstone volume; though it was an oversized hardcover, coffee-table style book—with dozens of richly printed full-page images which sold for at least $50 when it came out—in my Cleveland bookstore, Undercover Books, we ordered lots of copies, stacked it up, and sold dozens. The essay is by Mark Athitakis, a critic whose reviews I alway enjoy. He explains that Vishniac, who was born in Russia, not Eastern Europe, had scientific training, and after narrowly saving himself and his family from the Nazis, and coming to America in 1940, “he taught biology and photography at New York colleges and, in the ’50s and ’60s gained fame for his microphotography—high-resolution shots of live insects and colorful images of amoebas and protozoa and human tissue filled the pages of magazines such as Life and Boys’ Life.”

The film also reveals that during WWII, while the Holocaust was raging, Vishniac tried to use his pictures to influence policy, including inside the Roosevelt administration. Athitakis also explores something the film touches on—a tendency of Vishniac to write captions for his photographs that were not, shall we say, journalistically rigorous, and may have romanticized or idealized some of his subjects.

A connection to Roman Vishniac through Isaac Bashevis Singer

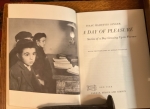

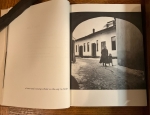

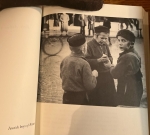

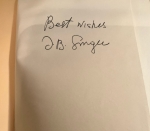

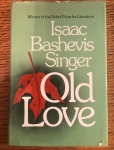

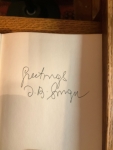

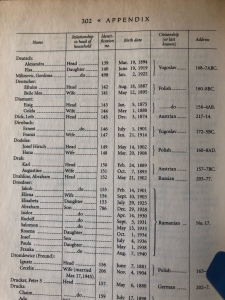

I worked with my siblings Joel and Pamela, and our parents, Earl and Sylvia, at Undercover Books from 1978-85. In 1979 I had an opportunity to take some books from our store inventory to a personal appearance in Akron by Isaac Bashevis Singer—who had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature the year before. I brought copies of some books of Singer’s from our inventory for him to autograph after a talk he gave. Among the books I brought were his then-current book of short stories Old Love (FSG, 1979), and another book we had in stock, A Day of Pleasure, a personal portrait by Singer of the lives of Jewish children in Poland before WWII, a small volume which was illustrated with photos by, you guessed it, Roman Vishniac. The latter is classified among Singer’s books as a book for children. It was of course published before the magnum opus collection that would be published to great acclaim just four years later.

It strikes me that when Vishniac took his pictures of a population so soon to vanish, while he surely must have feared the loss of the people, he could not have foreseen that those pictures would one day illustrate a book of childhood remembrances by a Jewish Nobelist writing about the pre-war period. Not to employ a colloquialism that would in any way trivialize the loss of millions of Eastern European Jews that occurred after Vishniac photographed them, and after Singer came to America, but an observer might be tempted to invoke the Yiddish word, beshert, meaning something that was “destined, or meant to be.” I don’t want to want to ascribe destiny to anything associated with the Holocaust, but I’ll just say I think it was mete and right that FSG thought to use Vishniac’s photos in Singer’s book, even before they published his big collection.

It seems that Roman Vishniac may have been a sort of house photographer for FSG, and that maybe when they used his photos in Singer’s book, the publisher and Vishniac were already anticipating the big book to come. The editor of A Vanished World, Michael di Capua, a long-timer in publishing, is interviewed in the documentary. di Capua was well known for doing children’s books, so maybe there is something to that idea of mine.

For a last word here on Roman Vishniac, I’ll just say that for him to have worked so brilliantly in the medium of human portraiture, and then later in life to embark on the scientific subject matter, highlights an amazing career with an aesthetic range that is kind of astonishing. His daughter Mara, who died in 2018, was interviewed by the documentarian Laura Bilias, the director of Vishniac. I hope to see her film. Until you get the chance to see it, I recommend Mark Athitakis’s essay, which is published on the site of the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), titled “Photographer Roman Vishniac Explored the Shtetl and the Scientific.” And check out the trailer of the documentary: https://vimeo.com/332316939

I don’t own a copy of A Vanished World, but I do still have copies of two books that were signed by I.B. Singer that day in Akron almost 45 years ago.

- Title pg A Day of Pleasure

- Teacher and boy

- Jewish Boys in Warsaw

- IB SInger signed

- Old Loved

- IB SInger signed 2