I was stunned by the new documentary, “Finding Vivian Maier,” which Kyle and I saw yesterday. Below is the trailer, if you haven’t seen it yet, or the film, which was directed by John Maloof, and two of her photographs. He bought a box of her negatives at an auction in 2007. At the time, neither he, nor anyone, yet knew who Maier was, or that she’d been making a photographic record in Chicago where she lived since around 1949.

I continued thinking about the movie all day after walking out of the noon screening. Today, I’m still mulling some major points that struck me. Below is an attempt to corral what I’ve been thinking about the film.

Vivian Maier (1926-2009) embarked on and then sustained over many decades the production of what we can now see as a truly monumental visual and documentary legacy. It’s a microcosmic yet vast history of modern urban America and many Americans, seen through the sensitive eye, lens, and mind of one person, a woman whose work as a nanny somehow allowed her the means and opportunity to conduct this personal journalistic enterprise. Until Maloof’s discovery, the enterprise was completely unknown, yet it was hiding in what amounted to (somewhat plain) sight, in auction houses, storage lockers, and in the records of the families she had worked for over the years. Some of them were still paying storage fees on her property. With impressive industry and inspired sensitivity to Maier’s mission, Maloof has excavated the extant physical record. I’m very thankful to him for doing this, for his open-heartedness and his willingness to plunge in to Maier’s work. In bidding at the fateful auction, he went all the way up to $380 for the box of negatives,* not small change. He said on WNYC’s Leonard Lopate Show last Friday that when he bid on and won the box he hoped to be able to harvest images from it for a photographic history of Chicago he was organizing for Arcadia Books (the publisher that does city histories). Turned out the pictures weren’t good for the book, and he put them in a closet. But sometime later, he posted more than 100 images on his Flickr page, essentially blogging with them. The reaction was a palpable “Wow” from street photography lovers and has led ultimately to this amazing documentary, which I want to see again.

Thinking more about Maier’s dedication, I’m amazed at how pure her motivation was in producing it all. She created this legacy, even though she never, so far as is known, sought an audience for her work, and had no child, relation, friend, or agent–not a single person–to whom she could leave her work; I wonder if she even had a will. Nor does it seem Maier solicited the interest of another photographer or an institution that might have taken an interest in her archive. Perhaps Maier knew best, not wanting to broach rejection. In the film, Maloof reports on what became a futile attempt to interest MOMA in the work. Even with their storied photographic collection, curated for many years by Peter Galassi, who didn’t retire until 2011, they perfunctorily declined. There ought to be some embarrassment at the museum over this and I think it would be a good thing if an arts journalist with a source at MOMA would seek on-the-record comment from them about their refusal. I concede that everybody makes mistakes–like editors who turned down On the Road and Catcher in the Rye–but it’s best to own up to them when they occur. So, instead of falling in to the hands of a responsible party at the time of Maier’s death in 2009, the hundred thousand negatives, many 8 mm and 16 mm film reels, and cassettes of audio recordings she made with people she interviewed–making her a veritable podcaster, decades before the term was coined–were basically put out to sea, cast adrift, and headed perhaps for a destructive crack-up on the rocky shores of time. That they didn’t suffer shipwreck–or submersion in a landfill–borders on a secular miracle.

I’m also thinking of Maier’s lack of an audience in a personal way, in relation to my own creative output, my two blogs (to be sure, humble by comparison). Here and on Honourary Canadian, I write and share about what interests me, what compels me, and hope that readers will care about these things, too, and appreciate the way I express and present them. I do like knowing that readers are finding items of interest and mutual relevance, though I wouldn’t change what I’m writing about just to gain more readers. It doesn’t matter greatly to me if some pieces aren’t widely read, because I’m also writing for myself, for the clarity of mind that I derive from the effort and experience. Fortunately, I do have readers, and what amounts to my own printing press, the WordPress blogs themselves. Maier, in this regard, didn’t seek, or at any rate, didn’t have the opportunity to have her work seen by others. Yet, she seems to have hardly flagged or despaired over not having a speck of an audience or appreciation, and no way to get them. This makes what she did all the more singular and remarkable.

On America’s most prolific diarist, Edward Robb Ellis; “Joe Gould’s Secret” by The New Yorker’s Joseph Mitchell; and Vivian Maier

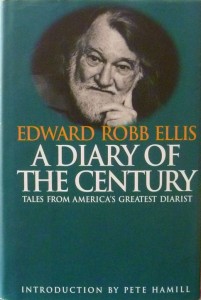

Readers who follow the books I’ve edited and published over the years may recall my author Edward Robb Ellis (1911-98), whose A Diary of the Century was quite a popular book for me, published in 1995, republished in 2008, still easy to find, still highly recommended. I mention it here because Eddie, as friends knew him, is the writer in my experience with an enterprise most closely analogous to that of Vivian Maier, though interesting distinctions exist between them. He kept a diary longer than anyone in the history of American letters, beginning his enterprise at age 16 during the Christmas vacation of 1927, when he dared a few pals, and himself, to start keeping a diary, and then they’d see who among them could keep it the longest. In his 20s, he also became a newspaper reporter. Basically, Eddie never stopped writing until the year he died. As Pete Hamill observed in his Introduction, Eddie wrote in print for the public, yet also for himself in the diary, which years later he wrote helped him become a more mature, an even happier, person. But even with the diary’s private reflections on intensely personal matters, Eddie also showed an interest in writing for the sake of the future, for posterity; he ultimately wanted the diary to be read by others, in hopes it might enrich the future with useful knowledge and pertinent information on his times–his entries cover the quotidian; the cost of things; which songs were on the hit parade; what movies were shown on a weekend when he worked his part-time job as an usher at the local cinema; along with current events and historic incidents that shook the world. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, which certified Ellis’s achievement in the early 1990s, his diary comprised more than 22,000,000 words, nearly half the length of the Encyclopedia Brittanica, a work with hundreds of contributors, while like Vivian Maier, Eddie created his work entirely on his own.

Ellis’s prodigious achievement was so well known among his fellow journalists that when Diary was published the week after Labor Day in ’95, Eddie scored a rare publicity hat trick: He was invited to appear, and went on all three network morning chat shows all within that week, interviewed by Cokie Roberts, Matt Lauer, and Harry Smith (on ABC, NBC, and CBS respectively) each network overlooking the usual policy they had against booking a guest who’s just been on a competing show. In the last decades of his life, the diary by then grown to many bound leather volumes and associated boxes, Eddie spent much anxious energy contemplating where his magnum opus might end up–he tried deeding it to a number of institutions, but even with the Guinness stamp of approval, there were few willing takers. Fortunately, as I wrote in a Preface to the 2008 paperback reissue of Diary, Eddie’s life work found “a permanent home with the Fales Library of New York University. Indeed, even before the last day of his life–which arrived on Labor Day 1998, so fitting for a man who always called himself a ‘working stiff’–more than five dozen oversize bound volumes were hauled from his Chelsea apartment to the Greenwich Village campus.” I added that I hope to publish another volume of the Ellis Diary someday, for it had been “my privilege to read into those bound volumes of the diary…and I promise the reader that I found no dross there.”

While working with Eddie Ellis from 1993-98, bringing out three other books of his, including The Epic of New York City, I came upon Joseph Mitchell’s classic New Yorker profile, “Joe Gould’s Secret.” In it, Mitchell chronicles for the reader his lamentable discovery that a longtime legendary denizen of lower Manhattan, Joe Gould, who for years had purported to be writing a magnum opus/History of the World was ultimately a bluffer, a failure, and a fraud. (In the pretty good movie version Ian Holm plays a grizzled Gould while Stanley Tucci takes on the role of Mitchell, a North Carolina writer working for the magazine.) Working with Eddie, I used to think how lucky I was to be working with a real-life Joe Gould-type, only Eddie was the real McCoy.

But now, thinking once more about Vivian Maier, I can see that unlike the others, she created her magnificent magnum opus without an audience, nor hope for one. By contrast, Gould hoped for adulation from others, though he did little to earn it, while Eddie Ellis, though not creating his work primarily for others, did enjoy praise, and came to see how his diary could be useful to others, and so arranged to share it with the world. But not only did Maier disclaim an audience for herself, she didn’t even claim posthumous credit for her achievement, like say with a “To Be Opened on the Occasion of My Death” letter, with information on where her affects could be found. She just died, and fortunately John Maloof was there to connect with her work. This is all a striking contrast to her male predecessors Gould and Ellis, the former phony, the latter authentic. It leaves me in greater awe of what she accomplished, and all the more appreciative of the documentary “Finding Vivian Maier.”

*I objected to the penultimate paragraph in Manohla Dargis’s

NY Times review of the documentary, where she quibbles with the fact that Maloof stands to gain financially as Vivian Maier’s star rises higher. The guy has unearthed this magnificent work, and devoted several years of his life to it, at much expense I’m sure–I hope he does well from it all. Glad to see that art critic Jerry Saltz and I are in agreement on this point, as he wrote this in

his New York magazine review of “Finding Vivian Maier”: “The Times’ otherwise excellent Manohla Dargis churlishly labeled this documentary ‘a feature-length advertisement for Mr. Maloof’s commercial venture as the principal owner of her work.’ This sort of cynical snappishness is cropping up a lot in many critics’ work of late—the idea that if there’s any profit involved, the work must be less pure, less good, more suspect. Whatever: I love this advertisement. Besides: Maloof tried to get MoMA interested in Maier’s work. In the film, he shows us and reads the perfunctory rejection letter he got from the museum. He was on his own. No one else wanted to take on the responsibility of unearthing and bringing to light this truly great artist. History will be grateful to him, and no one should look back cynically at his commitment to Vivian Maier.”