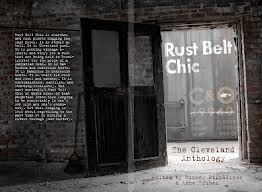

Senator Sherrod Brown ♥s “Rust Belt Chic”

So glad to be one of the 35 contributors to Rust Belt Chic: A Cleveland Anthology, with my essay, “Remembering Mr. Stress, Live at the Euclid Tavern,” on a venerable bluesman I followed avidly for years when I lived in Cleveland. Among the writers in the book is Connie Schultz, the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist who for many years worked at the Cleveland Plain Dealer. She has recently left the paper while her husband, Sherrod Brown, runs for re-election to the US Senate from the State of Ohio. Today, on the Rust Belt Chic Facebook page, I saw this, a note from Ms. Schultz:

So glad to be one of the 35 contributors to Rust Belt Chic: A Cleveland Anthology, with my essay, “Remembering Mr. Stress, Live at the Euclid Tavern,” on a venerable bluesman I followed avidly for years when I lived in Cleveland. Among the writers in the book is Connie Schultz, the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist who for many years worked at the Cleveland Plain Dealer. She has recently left the paper while her husband, Sherrod Brown, runs for re-election to the US Senate from the State of Ohio. Today, on the Rust Belt Chic Facebook page, I saw this, a note from Ms. Schultz:

“Sherrod didn’t get home until after midnight last night, but as soon as he saw my newly arrived stack of ‘Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology,’ he had to pick up a book and take a look. ‘Wow,’ he said, over and over, as he recognized one writer’s name after another, read aloud some of the titles and marveled at the photos.”

Nice, huh?

—-

At the time of Rust Belt Chic’s publication earlier this month, I cross-posted my essay on Mr. Stress and wrote these paragraphs to introduce the book to readers. Allow me to quote myself:

As a sign of just how community-oriented the book really is, editors Trubek and Piiparinen asked all the contributors, in the event that the book sells well enough to make back its expenses and reaches into profitability, would we want an honorarium payment, or would we choose to plow our earnings into another indie project to be chosen first from among book ideas presented by us contributors, with one (or if we’re really fortunate, more than one) project being chosen for funding. I have a ready book idea–a new volume to be culled from the Guinness Book of World Records-recognized diary of Edward Robb Ellis, whose A Diary of the Century: Tales from America’s Greatest Diarist, I edited and published in 1995. I was happy to choose the second option offered.

With all that said, I’ll continue this preamble by saying I hope you buy the book as a print or a digital edition, or one of each, not because of charitable intentions (though that’s okay too) but because it offers more than fifty fine examples of narrative journalism, chronicling a distinctive part of the country that is too often overlooked on the literary and cultural map. I also urge you to follow the book’s Twitter feed, @rust-belt-chic. On my own Twitter feed, @philipsturner, I’ve started a hashtag, #MrStress. You may also ‘like’ the Rust Belt Chic Facebook page. Thank you in advance for supporting this exciting experiment in cultural urban renewal.

—-

Thanks for your support of Rust Belt Chic: A Cleveland Anthology, and I hope you enjoy reading my essay on Mr. Stress, cross-posted here on The Great Gray Bridge.