Q&A with Paulette Myers Rich—Photographer, Printer, and Curator of No. 3 Reading Room & Photo Book Works

I’m handing over the blog today to my wife, artist Kyle Gallup, for a guest post in the first of what will be a series of interviews by her with artists and writers. Kyle last wrote for The Great Gray Bridge with a post on the painter J.M.W. Turner. I am really excited to publish this post, because it draws on the rich literary tradition of Minnesota, such a vital place in America for book arts and fine printing. —PT

—-

Paulette Myers Rich is a photographer, artist, fine art printer, maker and collector of artists’ books. She is also the curator of the exhibition space, No. 3 Reading Room & Photo Book Works in Beacon, New York. With Covid restrictions she has reoriented her space to show art in the front windows of her gallery. It seemed to me like a good time to check in with her and see how her own work’s going and what she sees for the future of her gallery space.

You moved from Minnesota to New York City and now upstate, to Beacon, New York. Can you tell me a little bit about what led you from the Midwest to the East Coast, and how this has influenced your work as a photographer and artist?

I was teaching and working in Minneapolis/St. Paul for many years, but major life changes prompted us to take time off to decide what would come next. My husband David Rich is a painter and educator who has deep roots in NYC and in 2012 we decided to spend a year there to immerse ourselves in our work and consider our next steps. The year turned into five before we completely relocated from Minnesota.

We had a live/work loft in lower Manhattan that gave us each a small studio space, but I was going back and forth from NYC to my letterpress studio in St. Paul for months at a time. Finding the right kind of space for my equipment in NYC was tough because so many larger studios have been chopped up into tiny spaces with high rent. I began looking north for a place on the train line and in 2015, finally found a derelict commercial building for sale on Beacon’s Main Street where we could live and work, although I wasn’t looking forward to yet another gut renovation. This became our fourth such project. We sold our St. Paul building, moved everything into storage until the renovation was done a year later, then moved from our loft in the city up to Beacon. I got very good at logistics.

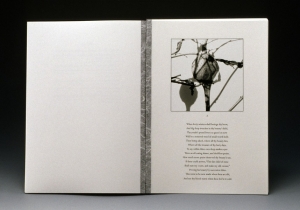

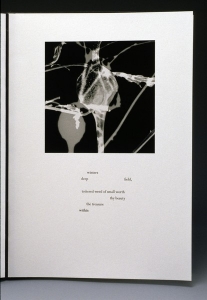

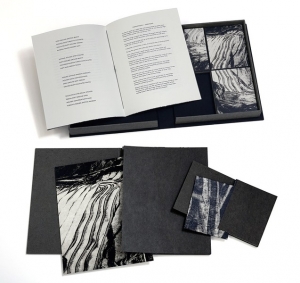

The move to Beacon allowed me to open No.3 Reading Room & Photo Book Works in the storefront adjoining my letterpress studio. It’s an extension of my studio practice, designed for viewing artists’ books, photobooks and small press poetry from my collection along with work on paper and photography by guest artists. Exhibitions of artists’ books tend to show the work in a vitrine out of reach with only a page spread on view, which was frustrating for me as an artist as my work is intended to be interactive. I decided to make a space where readers’ copies of my artists’ books are accessible to viewers. Books are meant to be handled and read and the experience is incomplete without this. No.3 offers visitors access to experience the entire book at their own pace in a context with related work. I also make myself available for conversation or questions as viewing books tends to generate a response and many times, looking at one book leads to another. It’s a form of engagement that’s rare in viewing art.

I also invite exhibiting artists to include personal copies of books that informed their practice, or alternatively, a reading list. The artists I show are readers and they’re generous in their sharing. Some of these books have traveled with them or were gifts from loved ones, many have marginalia and tabs that reveal what’s important to them. But if the artist needs to hold onto their books, I’ll acquire a reader’s copy to share. This hybrid approach to showing artwork opens up conversations in a meaningful way that doesn’t often happen in a commercial gallery.

I read that your photographs are about landscape, place, and time. How does your locale influence what you photograph?

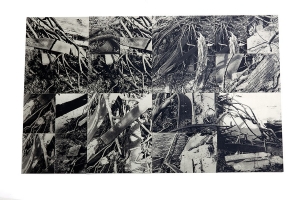

My current locale in Beacon and the Hudson Valley is new to me and I’m still exploring it. I’m surrounded by wilderness and mountains, which is very different from the urban post-industrial landscapes I’ve been living in and photographing for the past forty years. However, it’s the remove from familiarity that’s been most influential in my current practice. I returned to the studio about ten years ago, spending more time in what I see as a necessary and compelling phase of my landscape work, which means delving into my photo archives, revisiting these sites and reconfiguring them through collage and new juxtapositions. I’m also photographing constructed spaces that explore the metaphysical, mathematical and spiritual dimensions of place once again. There’s a quietude here that I’ve never had elsewhere that I find I need in this time.

Are there particular subjects and themes that you most gravitate or return to?

Most sites I photographed were once active industries on acres of land that were abandoned and left vacant in the midst of working class neighborhoods or along the Mississippi River, and there were many of them. It was hard for me to fathom how a company could just shut down, throw so many people out of work and walk away from such a massive property, usually very polluted, that we as residents had to deal with in the aftermath before gentrification. However, aside from the social indifference and environmental impacts that I contended with as a citizen at City Hall, as an artist, it was the mysteries of the site that I sought out; the lingering energies, the aftereffects of abandonment, evidence of the former life of the place, the encroachment of nature, and the momentary landscapes that emerged from the demolition process that combined to make strange, poetic juxtapositions and layers. I’m striving for that kind of mystery and energy in my current work in the studio through combinations of ephemeral installations and constructions set up for the camera, as well as in the reworking and reconfiguring of my Work Sites series photographs.

Your artistic practice is wide ranging, from photography, to fine art printing, to handmade book-making, to being a collector of artists’ books, and director of No. 3 Reading Room & Photo Book Works. How have these different aspects come about and how have they evolved?

I came to my photo-based artist book practice through experimental films I was making in the early 1970’s as a youth, at a media arts center called Film in the Cities, where I was immersed in contemporary alternative and experimental media projects. I was especially interested in film-as-film, where the material qualities of light, emulsion, grain and surface are a part of the content. But to continue making this work as a working-class mother of two required resources I didn’t have, so I scaled back to still photography, working experimentally, abstractly and sequentially to simulate the pacing of film. I exhibited this work as sequential stills but wasn’t satisfied with this form of presentation. It felt static to me.

When the Minnesota Center for Book Arts (MCBA) opened in Minneapolis in 1985, I became an intern in the papermaking studio to study sculptural techniques using handmade paper for still-life constructions, my primary photography subject at the time. Initially, I had no notion of making books, but when I was exposed to contemporary book art practice in MCBA’s studios and gallery, I realized I could reintroduce a sequential and temporal element back into my work, along with the tactility of materials and forms designed to activate the narrative. Eventually though, my industrial landscapes became my primary subject as it came to dominate my life in many ways.

I’ve always been a reader and novice writer and wanted to integrate poetry and text into my work, so I enrolled in the College of St. Catherine’s weekend program to study creative writing and library science, then returned to MCBA in 1990 to intern with Gaylord Schanilec in letterpress printing, entering the world of fine press books. I continued on as a studio assistant on various projects, mentored by master practitioners while taking workshops to acquire the skills I needed, learning a trade in the working-class tradition as an apprentice, which felt comfortable to me. I did this all as a working mother; I wish I still had that kind of stamina.

Eventually I became a master printer-in-residence with assistants of my own, overseeing projects and teaching at MCBA and local art colleges. I acquired my own letterpress equipment and set up Traffic Street Press, named for the street adjoining my studio in the North Warehouse District of Minneapolis. Along with my personal work, I collaborated with poets I admired publishing fine press books in my Trafficking in Poetry series, and also produced a series of contemporary Irish poetry books and broadsides with the Center for Irish Studies at the University of St. Thomas, in St. Paul.

In 1990, I also became a news librarian at the St. Paul Pioneer Press, where I did research for reporters, helped manage the photography collection and cataloged books. It was my dream day job, but soon after, newspaper publishing was hit hard as a business and in time, most of the library staff was eliminated. I then picked up extra teaching in book arts, mentored grad students, and produced and sold my books.

Even before my time at MCBA, I had collected small press poetry chapbooks from a used bookstore in my neighborhood near Macalester College that carried a range of them. St. Paul is a city with a cluster of liberal arts colleges and the used bookstores were goldmines for me. When Allan Kornblum became the first printer-in-residence at MCBA and moved Toothpaste Press from Iowa City to Minneapolis to start Coffee House Press, you could buy his chaps at the Hungry Mind bookstore, so I have a box full of them. There were a variety of small presses, writers, editors and book distributors in the neighborhood. I was in a rich literary environment and took advantage of this.

With Covid-19 restrictions affecting artists around the world, how have you dealt with the quarantine and in what ways has this affected your work, artistic process, and thinking?

I’m trying to remain disciplined, reminding myself that I’ve endured deadly and frightening times in other periods of my life. I looked to women artists who went through difficult times, reading biographies and journals as a guide. As a former Minnesotan, I’m accustomed to hunkering down for long, extreme winters so my home and studio have always been set up for that. I’ve been revisiting photographs from my archives, experimenting with new forms and spending time in No.3 doing research, writing and cataloging new books. I value the quietude and concentrated thought that books provide, but I miss my engagement with artists and the community, so in warmer months I use the display windows of No.3 to install exhibits which works well, and I’ll continue to do that.

But I must say there were times I couldn’t concentrate enough to read or work and instead watched a lot of news keeping up with what was happening back home in Minneapolis/St. Paul after George Floyd was murdered in a neighborhood dear to me, because this could happen to any number of people there that I love. And of course, the 2020 election was stressful. I avoided social media and instead, called friends to talk, which made each of us feel much less isolated. One night during the riots in Minneapolis, while talking to a friend who lives a few blocks from Lake Street, smoke from the fires came into her windows. I had friends on neighborhood watch with their guns and dogs because white extremists had infiltrated the cities, instigating a lot of the destruction. Friends documented cars with Boogaloo Boys logos and out-of-state plates, and they found incendiary devices hidden in their alleys and backyards. People had their garden hoses pulled to the front door and turned on in case they needed to put out a fire. It was traumatizing to see all this unfold on national media and hear even worse news from our friends and family living through it. I’m hoping that Chauvin’s guilty verdict will secure much needed, long overdue police reform and that justice will be served in the ongoing violent episodes that have happened since.

Meanwhile, I’m looking forward to emerging from this strange, isolating time. Initially, No.3 Reading Room will reopen by appointment or invitation, so I can keep it safe for those who visit. I’m going to stay hopeful about reopening more fully as a walk-in space. I really miss that part of my life and I know people need a place to go have some peace and spend time sorting out the last year as well as to plan for the future. Books and the reading room offer that space.

On your blog, you have a new exhibit, Walking the Watershed, Photographs by Ronnie Farley, that is part of a larger project and exhibition, Extraction: Art on the Edge of the Abyss. Can you talk about this project and how it relates to your own work and interests?

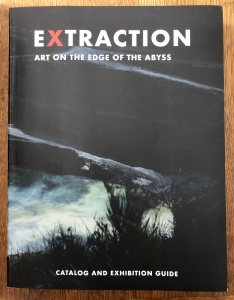

Extraction: Art on the Edge of the Abyss, was initiated by Peter Koch, a fine press book artist, writer, educator and co-founder of the CODEX Foundation, a non-profit devoted to fine press and artist book practice. Peter is from Montana and experienced the impact mining has made on the environment and people there. In 2015 he produced a book called Liber Ignis; “…a collaborative project of appropriations, inventions, and constructs documenting the ongoing war against nature in the American West…”

Extraction: Art on the Edge of the Abyss, was initiated by Peter Koch, a fine press book artist, writer, educator and co-founder of the CODEX Foundation, a non-profit devoted to fine press and artist book practice. Peter is from Montana and experienced the impact mining has made on the environment and people there. In 2015 he produced a book called Liber Ignis; “…a collaborative project of appropriations, inventions, and constructs documenting the ongoing war against nature in the American West…”

When Peter encountered the book Black Diamond Dust in the Dia Beacon museum bookstore about a year later, he was inspired by this multi-site arts action about the impact of the extractive industries in Vancouver Island, B.C., and decided to initiate something similar in Montana about the mining industry there, but it expanded to a much larger scale and became what he calls a “global Art Ruckus.” I was supportive of this project early on, having photographed, lived near and worked in industrial landscapes set in big nature for many years, so I’m well aware of the impact these industries have on our environment. I’m honored that No.3 Reading Room & Photo Book Works is included as a site for exhibiting artists who focus on these environmental issues in their work as a part of the Extraction project.

Ronnie Farley is a photographer and writer I admire very much. Her work is deeply concerned with the environment and the Indigenous women who have been fighting polluters for decades. Her recent Walking the Watershed project features photographs from her 150-mile trek from the Schoharie Reservoir, following the path of the aqueduct that delivers water to NYC. She made it in stages, carrying a bucket of water from the reservoir and giving talks in each community she passed through. When she arrived in NYC at the end of her journey, she poured the water into the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir in Central Park, “returning the water to itself.” Ronnie lived in NYC for many years but is from upstate and wants New Yorkers to know what a long distance their drinking water travels and how fragile and precious it is. She has a companion book and film that will be completed soon that I’ll also feature.

Throughout 2021, I’ll be showing the work of painters, sculptors, printmakers and filmmakers, alongside books relating to their specific topics, including Black Diamond Dust. The Extraction project has produced a comprehensive catalog called the Megazine (pictured above), featuring writing and images by participants. I’ll be giving away 100 copies throughout the summer to visitors.

What have you been reading over the last year?

I’ve been reading across disciplines, but the books that stand out for me are the biography and poems of Paul Celan, essays by Audre Lourde, and the new anthology Women in Concrete Poetry, 1959-1979. I’m also reading Ninth Street Women, by Mary Gabriel; Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars by Francesca Wade, and Frantumaglia: A Writers’ Journey by Elena Ferrante. I’m always looking at new photography books, but Alessandra Sanguinetti’s The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer is a favorite, but there are too many more to mention; my research covers everything from industrial handbooks of the late 19th century to theory. One thing leads to another when you read.