Ruth Gruber April 2007

A few months ago, while undergoing an ultrasound for something disconcerting I’d found on my body—which mercifully turned out to be, officially, nothing—I was suddenly hit by a wave of gratitude for an old friend: author and photojournalist Ruth Gruber, who despite our wide age gap was one of my closest confidants, and even at times a surrogate grandmother.

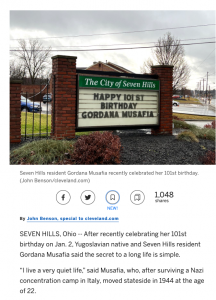

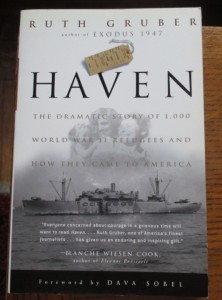

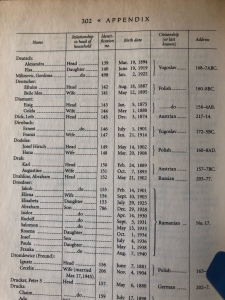

The reason for my gratitude was simple: in 1944, as a newly appointed general by the Roosevelt Administration she personally escorted 972 refugees to America; many, though not all, were Jewish. Among these refugees was a man named Alex Margulis who, as chronicled in Ruth’s 1983 book Haven, would go on to invent the CT Scan, MRI, and other examples of medical imaging technology which have saved an unfathomable and beautifully absurd number of lives. As I was having my procedure I couldn’t help but think of Ruth, and all she meant to me, and to the multitude of people who knew her. After passing away in 2016, at the age of 105—nerd that I am, I admit it’s titillating to use the actual numerals for her age, as in the Chicago Manual of Style only numbers under 100 are spelled out—she left behind a legion of admirers, followers, and yes, even fans. I consider myself as belonging to the latter category, but at the start my connection to her was a personal one. Yet beyond personal and professional appreciation lies my aforementioned feeling, gratitude: especially as the technician utilized that life-saving device and informed me with a wink that, because the doctor did not want to see any more, I was “good.”

***

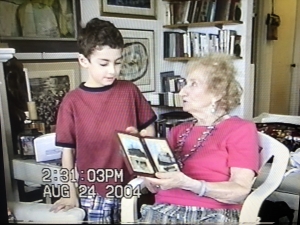

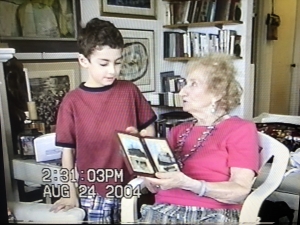

I don’t recall the first time Ruth and I met, but it had to have been around my seventh or eighth year—as in 2004, when I was still very young I subjected her to an interview, filmed by my mother on a camcorder, one steamy day in August, while I was on summer vacation. I still have the video, rendered into digital form but no less evocative of that early VHS period: amid wavy lines there I am, in almost knee-high white socks, sitting lackadaisically in a stuffed armchair, rattling off a list of question I had memorized, forgotten, then memorized again; while Ruth herself, looking dignified and very well at just ninety-three, listened and nodded and tried with honesty and precision to answer my questions—the questions of an eight year old who was very much wowed by her, and kept repeating after her every statement “That’s a great answer!” in an effort to impress a woman who could not have been kinder-hearted or more willing to engage with a young person.

It is important to stress the reason for my early acquaintanceship with her which soon blossomed into a friendship: my father was her editor—and according to a quip she made on more than one occasion at dinner parties and events to the chagrin of some present, he was her favorite editor. This favoritism was likely rooted in her appreciation of his no-nonsense editing style, and his direct, fearless approach to publishing. It matched her own brand of journalism, which was in the words of one of her mentors Edward Steichen to “Take pictures with her heart.” Not only did she take pictures with her heart, she wrote with it too! As any of her readers know there is a declarative majesty to her prose that is only outmatched by her subject matter; she had so much to say and a great deal of life experience to back it up—whether becoming the youngest Ph.D. in the world, doing so in Germany in the mid-thirties and seeing the tail end of the Weimar Republic give way to Nazi Germany; or having tea with Virginia Woolf in London—the very subject of her thesis—and being struck by the author’s corrosive nonchalance, and low-grade anti-semitism, while still managing to hold a nuanced view of her; or when in 1944 she, as mentioned, escorted by ship nearly a thousand refugees who were escaping persecution in Europe, and fighting for them to be accepted by the virulently anti-immigrant State Department, despite President Roosevelt being considered a friend to the Jews.

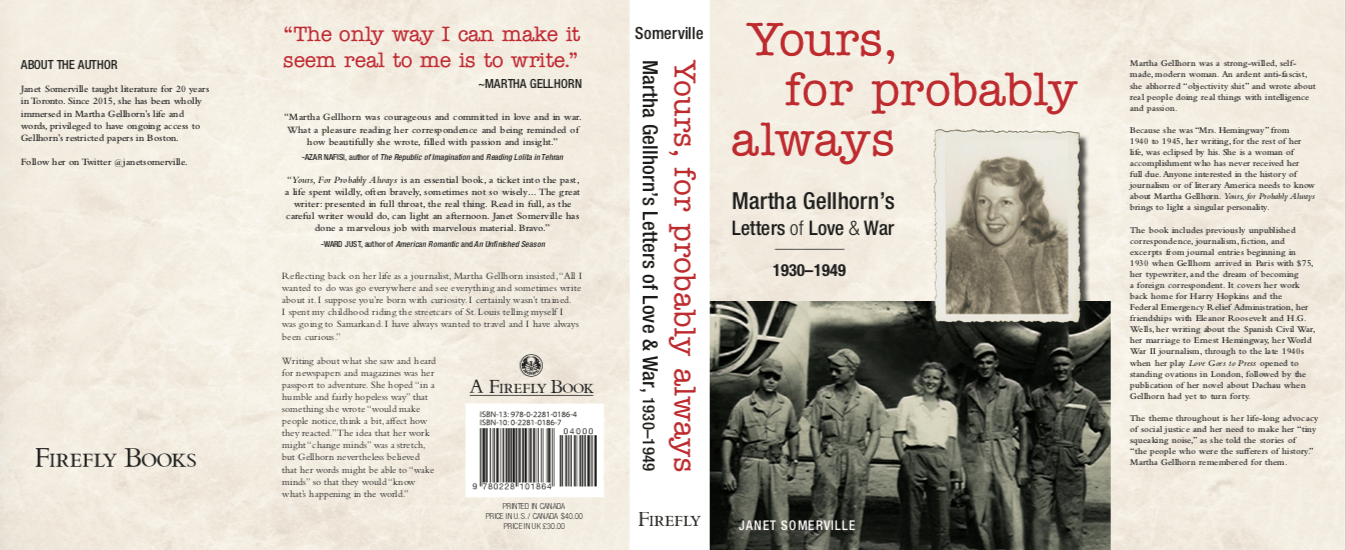

This is to say, she had something unique—content. Like other, more famous writers and journalists of the time—Hemingway, Dos Passos, and Gellhorn come to mind—after literally living her stories, she put her experiences into words that could be understood by everyone. But her egalitarian style permeated not just her written work but the way she spoke about her career—this held even while speaking about it to me on that sultry day in 2004 when my mom and I stopped by to see her to conduct and impromptu interview. There would be many days and evenings like this, when we would look at each other, and one of us would ask: “Do you want to go see Ruth?” and the answer was always, invariably, the same.

***

Ruth had been living in the Eldorado—a quintessentially regal Central Park West apartment building—for several decades when I first became acquainted with her. Just going over there was a grand experience for me; at the time I had not yet glimpsed New York’s magisterial splendor; the lobby looked like an art deco palace. But visiting Ruth was the start of something more than architectural or stylistic appreciation. I can easily recall these visits as the first time I considered an importance beyond the aesthetic; or rather, that the aesthetic and the moral and meaningful could coalesce into something highly impactful: the notion that one’s life could be an adventure.

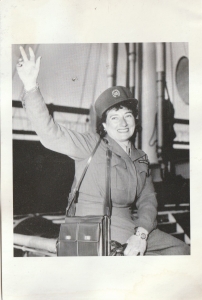

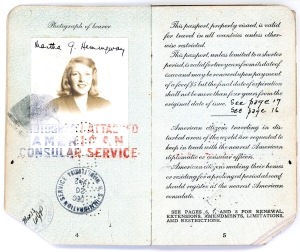

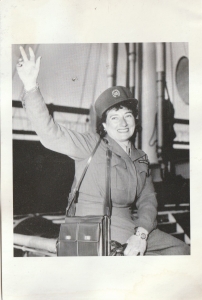

Ruth Gruber embarking on the voyage to bring nearly 1000 refugees to America in 1944. They sailed from Naples, Italy, crossing the Atlantic protected by a convoy of US warships. The story is told in her book, “Haven,'” and the 2000 CBS miniseries of the same name, with Natasha Richardson cast as Ruth.

It was this adventurous spirit that Ruth embodied, as well as a presentation of self that prized dignity and demeanor. Whenever we saw her—it didn’t matter if we had come on three consecutive Sundays—she got dressed up; always with her light gold hair perfectly coiffed; her jewelry always tasteful; her greetings broad and demonstrably delighted, as if she wanted us to know, really know, how glad she was that we had stopped by. And we stopped by many times, whether to simply have tea and talk, or to take her out to Central Park, or even have dinner with her.

It was on these nights that my conception of an intellectual community was formed—namely that such a thing could exist, and that I could be a part of it. This feeling carried over into my schooling; in college I had the unique experience of going with my archives class to visit the New York Public Library to see Virginia Woolf’s diaries, which my friend had been mentioned in, however unkindly by the sadly disturbed writer, whom Ruth saw as a woman trapped by her own mind. Though Woolf used an anti-semitic slur in her journal to describe Ruth, she did not hold a grudge beyond feelings of sadness and disappointment.

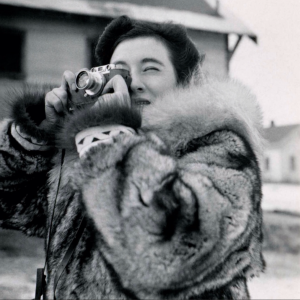

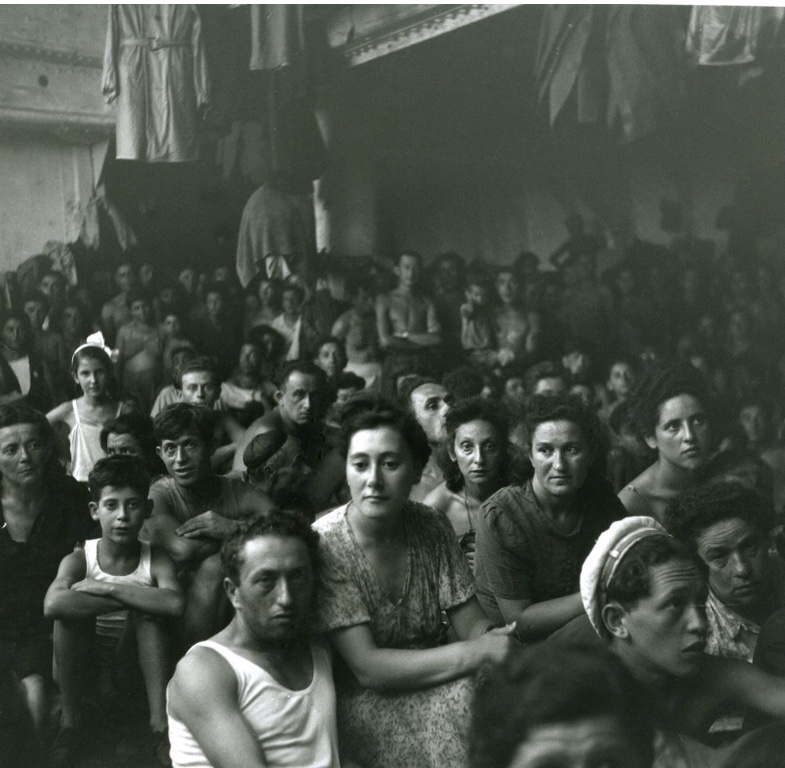

Ruth Gruber photo “The Embrace”

While I stood with my class looking at Woolf’s pages—most of which were written in a flourishing lavender hand—I knew that among them were those referring to my friend.

Despite Woolf’s callousness, I cherish these kinds of synchronicities. Growing up in New York brings one into the vicinity of great people, particularly if your parents happen to know some of them. These same great people can in their own way sum up entire eras, especially if the person in question is a centenarian. Ruth was born under President Taft and died in November of 2016 while Barack Obama was mercifully still President—though about to leave office to make way for the degraded eventuality that was to come. In one final act of goodness, to add to her litany of mensch-like deeds, the recently turned 105-year-old was taken by her daughter to the polls and cast her last vote for Hillary Clinton. It is unclear whether in the coming hours Ruth was cognizant of the election results, or fully grasped their implication, but it didn’t matter, for she had raised her voice one more time. This was something she’d grown accustomed to, whether from her efforts to counter the anti-semitism and isolationism of the United States government; or in 1944 reporting for the NY Post on the fate of refugees on the ship Exodus; or her early contributions to the newly-named field of Feminism in the 1930s.

***

Ruth Gruber is showing me a hinged, painted case my mother, artist Kyle Gallup, made. Inset in the case is a collage Kyle also made comprised of photos Ruth took documenting the refugees on the Exodus ship. It became part of the cover art for Ruth’s book—”Exodus 1947: The Ship that Launched a Nation”—which my father published with Ruth in 1999.

Despite her far-reaching influence, my dearest recollections of Ruth remain rooted in more personal soil. She was simply an older woman whom I cared for, and who at times felt like a surrogate grandmother to me. Given that my biological grandparents lived far away and I did not see them often, Ruth became a special friend, who was not relation nor teacher, but a figure whose influence was hard to define or put into a single box. It was in fact so unique, that, due to my own immature faculties at the time, I was unable to fully comprehend how lucky we were to know her and be close to her.

Yet where nomenclature fails, one recollection appears to sum up this relationship. And it was that, in my third grade year, she took it upon herself to attend Grandparents Day on my behalf. While most children had their family relations with them, Ruth was at my side, explaining who she was to the awed faces of the class. I remember my mother thanking her, and Ruth saying it was her pleasure—in her parlance everything was almost always “her pleasure”—and walking her back to her Central Park West apartment building where I knew we would soon have another one of our special get-togethers. Sometimes the canvas of memory is confused, disjointed, opaque; but not my memories of Ruth. There is a single beam of clear light which is cast upon all my imagistic renderings of her, and it starkly illuminates the privilege of having sat in her company, of hearing her stories that always seemed to conclude thematically with the victories of dignity over oppression, of passion over indifference—I took these tales to heart without deciding to, for there was something so indelible about her influence. Among her many gifts was the ability to make you feel that life could be made better by the simple act of putting pen to paper, or pressing the camera shutter. Sometimes the simplest actions have the greatest impact; sometimes saving one life can save many others.

Ruth’s influence transcends an easily measurable calculus; many close to her said if she had been a man she would have won the Noble Peace Prize, but Ruth herself did not think in those terms. She simply did the work she was passionate about, and believed to be right, and encouraged others to do the same. For a long life well-lived what more can anyone ask?

M. G. Turner

October 1, 2022

The Book Buzz panel put on by Publishers Lunch last night was terrific. Four great new novels and one science biography, with the authors appearing one after the other in conversation with their editors. The picture to the left shows the lone nonfiction author, Dava Sobel whose upcoming book is The Elements of Marie Curie: How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science. She discussed it with her editor George Gibson of Grove Atlantic. The narrative focuses on the Polish-born two-time Nobel Prize-winner (in Physics and Chemistry) Madame Curie (1867-1934) and the forty-five women scientists whom she mentored and did pioneering research with in her laboratory in Paris.

The Book Buzz panel put on by Publishers Lunch last night was terrific. Four great new novels and one science biography, with the authors appearing one after the other in conversation with their editors. The picture to the left shows the lone nonfiction author, Dava Sobel whose upcoming book is The Elements of Marie Curie: How the Glow of Radium Lit a Path for Women in Science. She discussed it with her editor George Gibson of Grove Atlantic. The narrative focuses on the Polish-born two-time Nobel Prize-winner (in Physics and Chemistry) Madame Curie (1867-1934) and the forty-five women scientists whom she mentored and did pioneering research with in her laboratory in Paris.