The Tragedy of Bruno Schulz, A Mysterious and Captivating Writer by M. G. Turner

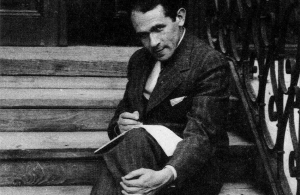

Reading the Polish-Jewish writer Bruno Schulz is an experience like no other: scholars have compared him favorably to both Franz Kafka and Marcel Proust. However, each of these authors provides only a partial analogy, despite Schulz’s work exhibiting the absurdity of the former and the nostalgia of the latter. But even with these similarities to existing storytellers, he is his own man, a wild, surreal magician of the written word who could conjure whole worlds right in his hometown of Drohobycz—then Poland, today Ukraine. In addition to being a linguistic marvel, he was also an accomplished illustrator of his own work, drawing bizarre phantasmagorical images which often featured a distorted version of himself.

Reading the Polish-Jewish writer Bruno Schulz is an experience like no other: scholars have compared him favorably to both Franz Kafka and Marcel Proust. However, each of these authors provides only a partial analogy, despite Schulz’s work exhibiting the absurdity of the former and the nostalgia of the latter. But even with these similarities to existing storytellers, he is his own man, a wild, surreal magician of the written word who could conjure whole worlds right in his hometown of Drohobycz—then Poland, today Ukraine. In addition to being a linguistic marvel, he was also an accomplished illustrator of his own work, drawing bizarre phantasmagorical images which often featured a distorted version of himself.

Schulz is one of the few deceased writers I have ever felt creatively jealous of, for he achieved something on the page which is extremely elusive and usually relegated only to the medium of cinema: the ability to transmit surrealism into fiction. There are some technical reasons why fiction does not lend itself well to this style; in film, directors can move from image to image at will, while with words we must always be building and rounding out our world, as well as shoring up our grammar, and at the same time constantly keeping in mind the reader who may at any moment put the book down. However inexplicably, Schulz does both of these things—that is to say, building a world and transmitting surrealism—to powerful effect. He crafts confounding fables of a family in turmoil, of a son bewildered by his father, of a city where the rules of reality are supplanted by a magical dream logic that sweeps the characters and the reader into rollicking journeys of remarkable and sublime poignancy. And despite the inherent darkness of this world, in which it always seems to be night, it is truly a delight to go with him. Another literary feat he manages to accomplish is making the harsh realities of Jewish life in pre-war, and then war-torn Poland seem beautiful and in, its own way, holy. For there are no laments or complaints in his prose, or even dirges on suffering; rather, his work, in its own roundabout way, appears to be a celebration of the human imagination and its ability to influence and effect our lives in a palpable and entertaining fashion. Not to mention the fact that, like Kafka, his characters are not recognizably Jewish.

Still, the fact Schulz was Jewish—and later murdered by a jealous S.S. officer who resented his artistic endeavors, while walking home with a loaf of bread—does lend the work a feeling of impending doom. Like Kakfa, he is perpetually aware of his own perceived inadequacy and manages to fight this psychological oppression by saying in effect, “Okay, you’re right, I am hideous and inferior. But so are you, and more so—you are agents of darkness while I am only an agent of the strange.” This is my own rendering of what I take to be Schulz’s overarching idea and modus operandi. The world he permeates with strangers and drifters and birds and hats with a will of their own has no hue or whiff of evil to it; instead, confusion seems to be its main characteristic and echoes what he and his family must have been feeling at the height of the war when they’d been forced into the Drohobycz ghetto by the Nazis and their Ukrainian collaborators.

The confusion present in his two story collections—the only ones that survive, as the rest of his literary output, including a novel called The Messiah, is lost to history—has a logical conclusion, and that is madness. A sense of madness was what Schulz must have been feeling as his family members were taken away, a sense of the vicious absurdity of trying to be an artist in a world that was crumbling around him. If it was driving the author mad, it made sense that the characters themselves are occupying a mad world where the laws of physics are suspended, or else don’t even apply. But in fiction, unlike in life, this kind of societal collapse can be rendered beautiful and even, to the reader, pleasurable to read—and all for its dream-like qualities which are born of the author’s escapist fancy and aesthetic brilliance. We enter a trance when reading Schulz, a healing type of meditative state, that even in the English translation by Celina Wieniewska (Schulz wrote in Polish) is distinct from the kind acquired from reading Kafka or Proust. This is due to the writer’s fusion of linguistic excellence with unbridled imagination that reveled in knowing no bounds—especially as his external world became increasingly cramped, closed-in, and imprisoning.

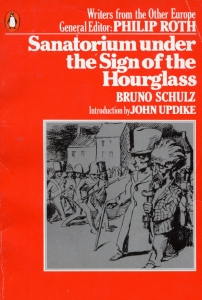

Schulz’s best story, I believe, is “Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass,” a must-read for anyone interested in dream logic pushed to its most extreme. In this story the narrator’s father has died; yet he remains alive in only one location, a mysterious sanatorium where the rules of life and death go unenforced. Time is the key element here: in the sanatorium his father’s death simply has yet to occur, and it is here the narrator finds himself visiting the man whose antics have plagued him for many consecutive stories. Some scholars have pointed out the similarity of this theme to those of Franz Kafka whose issues with his own father were often on display in pieces like The Judgment, and of course The Metamorphosis. But instead of making us feel, as Kafka does, that the author is finding comparable metaphors in fiction for the most intense emotions in his own life, Schulz takes a more nebulous and, in many ways, more nuanced approach. There is simply no resolution in “Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass,” or really in any of his work. This mirrors the writer’s own death. As stated earlier, Schulz was shot down in the street at the age of fifty by an S.S. officer who did not appreciate Schulz’s artistic efforts—efforts he was lending to a rival Nazi commander who’d contracted his services to paint a mural of fairy tales on his children’s bedroom wall, in exchange for money and some degree of protection, which in the end did not save him. (This mural is now restored and on display in Israel’s Yad Vashem World Holocaust Remembrance Center.)

Schulz’s best story, I believe, is “Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass,” a must-read for anyone interested in dream logic pushed to its most extreme. In this story the narrator’s father has died; yet he remains alive in only one location, a mysterious sanatorium where the rules of life and death go unenforced. Time is the key element here: in the sanatorium his father’s death simply has yet to occur, and it is here the narrator finds himself visiting the man whose antics have plagued him for many consecutive stories. Some scholars have pointed out the similarity of this theme to those of Franz Kafka whose issues with his own father were often on display in pieces like The Judgment, and of course The Metamorphosis. But instead of making us feel, as Kafka does, that the author is finding comparable metaphors in fiction for the most intense emotions in his own life, Schulz takes a more nebulous and, in many ways, more nuanced approach. There is simply no resolution in “Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass,” or really in any of his work. This mirrors the writer’s own death. As stated earlier, Schulz was shot down in the street at the age of fifty by an S.S. officer who did not appreciate Schulz’s artistic efforts—efforts he was lending to a rival Nazi commander who’d contracted his services to paint a mural of fairy tales on his children’s bedroom wall, in exchange for money and some degree of protection, which in the end did not save him. (This mural is now restored and on display in Israel’s Yad Vashem World Holocaust Remembrance Center.)

Perhaps Isaac Bashevis Singer said it best, when he lent a blurb to the publication of Schulz’s work, that had he “…been allowed to live out his life, he might have given us untold treasures, but what he did in his short life was enough to make him one of the most remarkable writers who ever lived.” I could not agree more. I highly recommend delving into this mysterious and tragic author if dream logic, surrealism, and magical realism appeal to you—though he is so much more than any label, name, or genre, can stick to him. In life he defied convention, and in death he did the same; thus, his immortality as a mid-century European literary master, albeit one who died before their time, is unquestionably assured.

January 2025