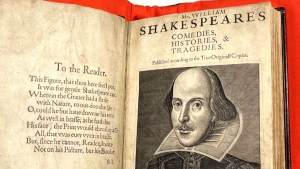

The Shakespeare Authorship Conundrum Society met Thursdays at the public mansion on Riverside Drive and 107th street. It was there that Theodore Gurney, Teddy for short, had found his confidantes—a ragtag gang of young and old aesthetes united over the dubious though benign conspiracy theory that the Bard of Avon was not the author of the greatest plays ever written. And in a culture plagued by misinformation of a more destructive sort, their little club wasn’t doing much harm. In fact, it was a delight to meet each week especially on those often rainy April afternoons and discuss, argue, and interpret. Everyone there was well-educated and a lover of the Bard’s work—that is, whoever the Bard actually was.

The Shakespeare Authorship Conundrum Society met Thursdays at the public mansion on Riverside Drive and 107th street. It was there that Theodore Gurney, Teddy for short, had found his confidantes—a ragtag gang of young and old aesthetes united over the dubious though benign conspiracy theory that the Bard of Avon was not the author of the greatest plays ever written. And in a culture plagued by misinformation of a more destructive sort, their little club wasn’t doing much harm. In fact, it was a delight to meet each week especially on those often rainy April afternoons and discuss, argue, and interpret. Everyone there was well-educated and a lover of the Bard’s work—that is, whoever the Bard actually was.

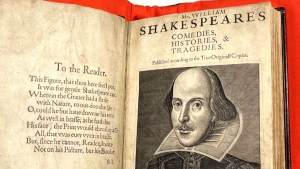

For some it was Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Several of his close family members had, according to Bennet Leach, a forty-three-year-old professional fact checker, been the supposed Shakespeare’s patrons. He, as well as several others in the group, adhered to the idea that Old Will was indeed a real person, but more of a steward, a frontman for the work of someone else who for reasons of political impropriety could not go public with their quill. How, this particular faction argued, could an uneducated man of humble background, whose father was a mere tanner, have written so penetratingly about kings, queens, and other members of the royal elite? How could he have always had the inside scoop on court intrigue? He couldn’t, they claimed—hence the existence of a secret that, if confirmed, threatened to unseat nearly five hundred years of orthodoxy surrounding the Bard’s majestic output.

But Teddy didn’t fall into this category. Nor did he fall in with the others, some of whom claimed Shakespeare was a Sicilian by the name of Collolanza who’d supposedly been puttering around England at this time, or that he was in fact Christopher Marlowe himself, who’d inexplicably succeeded at faking his infamous barroom death. Nor did Teddy believe he was one of the kings and queens who graced the English, French, or Spanish thrones, whose names over the course of centuries had been tossed into the hat for consideration by amateur critics and armchair scholars.

It is important to note that Teddy’s own belief about the veracity of Shakespeare’s genius lay in a more considered, accurate, though certainly less exciting realm. His own postulation which had come to him after several weeks of attending the Thursday meetings and taking in all the diverse opinions—as well as doing frenzied research of his own—was that Shakespeare was indeed Shakespeare, but that, seeing as he was part of the consummate Elizabethan repertory company at the renowned Globe Theater, many of the plays, including some of the most famous might have been written, or edited, or looked over by actors, namely Richard Burbage, who some scholars had even gone so far as to posit as the unacknowledged co-author of Hamlet.

But amid all the wild theories that dove inside his ears each week Teddy felt reluctant to lay bare this, by comparison, banal theory. To him the very fact of its subdued suggestiveness made it more stirring than say, the unsubstantiated idea that Shakespeare was really Sir Francis Drake, composing plays and sonnets while circling “the whole globe.” Thusly, it wasn’t until the sixth week of his involvement with the Society as he was now thinking of it, that his courage became plucked up enough to share his hypothesis. He decided to begin by validating all the other theories he had heard that day and in subsequent weeks before pouring the proverbial cold water on the wildest of them. “Never in my life,” he began, “have I had occasion to enjoy such compelling and consequential talk. But there is another theory which has gone neglected that I would like to share with you today.”

The faces of his co-conspirators glimmered under the resplendent lights of the Library Room. Several of them smiled, while some looked demonically expectant, as if daring him to outdo their spirited reveries.

“Go ahead, please,” said Margaret Crawley—a sixty-four-year-old librarian who was on the verge of retirement and was herself planning a “truth-seeking trip” to Stratford-upon-Avon, aka “The Birthplace” in the fall. “You have not spoken much in our meetings and we’d all be glad to hear from you.”

“Well,” Teddy cleared his throat. “As I see it, none of us will soon get the validation from academia required for a public acceptance of our theories, but there is one suggestion made by some scholars whose names I can share that seems to me almost indisputable.”

After a shared gasp there was a round of excited voices—some angry and some mortally pleased. Teddy went on:

“It is that, seeing as the Globe was a place of collaboration and collective creativity, portions of the plays—maybe even large portions of them—could have been contributed by the actors. It has even been suggested that the renowned thespian Richard Burbage—and in some ways the Bard’s right hand man—took a leading role in not only the production but in the writing of Hamlet. Who knows how many times an actor would flub a line, but in the process of this divine accident make it sound even better than it had been written on the page and Old Will watching from the back of the theater might have called out: ‘Forsooth, that is better than what I had quilled! Leave as is.’

“And though this line of thinking cannot be expressly proved it cannot be expressly refuted either, which I think lends it a great deal of credence and intellectual power. I would love to know your thoughts.”

As Teddy stopped speaking a great silence filled the Library Room, which was only broken several seconds later by Lloyd Hanger, a fifty-seven-year-old linguistics professor who was the unofficial “heavy” of the group, “THAT IS TREASON!”

“Yes! How absurd!” came another voice, which was met by a second chorus, some in defense, some in derision:

“I think Teddy has a point!”

“What does he know, he hasn’t even spoken until today!”

“But of all the theories his makes the most sense!”

“Don’t forget about Edward de Vere—you can’t explain him away!”

“I think this young man just did.”

“Oh, poppycock.”

“Care to take it outside?”

“I’d like to.”

“SILENCE!” This one word, from the instigator of the unexpected skirmish, quieted the rabble. Especially as Lloyd added: “Do we want to get kicked out of here?”

“He’s right.” Margaret let out a deep, feeling sigh. “This idea you have presented to us, Teddy, has certainly raised the temperature. How curious too, considering it is one of the most moderate we have heard. However, so as not jeopardize our position here, I suggest we move on to other business.”

With that mild word the war had been put down and Teddy sat in silence, unsure if another contribution of his was apt to be considered. But truthfully he didn’t have one and when he walked out that April day, after saying goodbye to his co-conspirators he made a silent vow to not return. For as the rain pattered down upon the earth and misted the Westside in its dew he felt as if he could, like Schrodinger, see all the possible identities of Shakespeare both having existed and not. He was simultaneously a great naval-man, a great earl, a great king, and a great scholar. He was a Sicilian wanderer and Miguel de Cervantes. But something all these theories seemed to reject, and something all the theorists seemed allergic to was that someone of so humble a background could be imbued with genius. Like most conspiracy theories, it neglected to consider a bare, and perhaps humdrum truth—in this case, that the embers of creativity can spark anywhere resulting in a blaze so tall and great we remain in awe for hundreds of literarily blessed years after.

And some five hundred years prior, in a green corner of jolly old England a bard was brought into the world—though in the minds of the most benignly credulous, who he truly was we’ll never know.

M. G. Turner

New York City

December 2023