Ray Harryhausen: Special Effects Pioneer and Childhood Hero by M. G. Turner

When I was eight years old I had the privilege of meeting one of the greats—in fact the greatest cinema special effects pioneer of the 20th Century. That man’s name was Ray Harryhausen, and to movie fans worldwide he represents the start of a great age in filmmaking, where the previously unthinkable could be projected on screen, using two primary techniques, known as Stop-Motion Animation, and Dynamation, which each pushed the boundaries of what had previously been possible in the fantasy, adventure, and sci-fi realms. But to me, Ray Harryhausen, for all his cinematic splendor and cultural renown, represented something else: magic. For me, this took the form of an idea, that art was not only impressive and important, that it could also be fun.

When I was eight years old I had the privilege of meeting one of the greats—in fact the greatest cinema special effects pioneer of the 20th Century. That man’s name was Ray Harryhausen, and to movie fans worldwide he represents the start of a great age in filmmaking, where the previously unthinkable could be projected on screen, using two primary techniques, known as Stop-Motion Animation, and Dynamation, which each pushed the boundaries of what had previously been possible in the fantasy, adventure, and sci-fi realms. But to me, Ray Harryhausen, for all his cinematic splendor and cultural renown, represented something else: magic. For me, this took the form of an idea, that art was not only impressive and important, that it could also be fun.

I can’t recall which Harryhausen movie I saw first, but it was probably Jason and the Argonauts, which remains my favorite of his films, though Mysterious Island is a close second. In those days—the early 2000s—I used to watch films on our bulbous, analog TV set. This included VHS tapes and eventually DVDs that we rented from our neighborhood video store and some of the first films I watched were Harryhausen’s. Something I used to do, in lieu of being in a real theater, was use chairs, pillows, and then a large bed-sheet to create a kind of makeshift fort, inside of which I could watch films. This had a curious cave-like effect and helped pull my focus to the images on screen, which were dazzling, especially to my young, uncritical mind. This was long before IMAX, and 48 frames per second, and on the fly CGI; this was an only child discovering one of his first artistic heroes, a man I would go on to meet, whom I would initially correspond with over a series of letters, first sent in the fall of 2003.

At that time I was starting second grade, and for my first two years in school had faced a great deal of bullying and harassment from other kids. I was always shy and quiet, preferring to read Harry Potter or The Lord of the Rings instead of running wild with my classmates on the playground. As many people are subjects of bullying and intimidation early in their school years, I don’t suggest I was unique in this, but do think it intensified my wish to escape into other worlds, to lose myself in some grand swashbuckling action. I was looking for something to fill the void, and though the Lord of the Rings trilogy, and the Star Wars space opera did some of the work, it was really Harryhausen who made me feel complete, Harryhausen who opened my mind and showed me that movies could be both entertaining and meaningful. In short, that they could be art.

With my mother herself being a visual artist, I already knew that art was an important element of one’s emotional and intellectual life, but I didn’t know it could also be fun. Seeing Harryhausen’s creatures come to life not only felt like the most special sort of magic trick, but an experience akin to walking through the halls of a wondrous and thought-provoking museum, which in those difficult days of 1st Grade helped me see that there was something outside of the difficult, tedious, and at times Kafkaesque experience of New York public school with its inane standardized tests, its lack of discipline, and myriad bureaucratic cruelties.

Thus I escaped into Harryhausen’s movies, watching them on the weekends, and sometimes on school nights. I even watched all the Sinbad films in succession when recovering from a traumatic ear operation. Because I was so moved by them, and because they meant so much to me, and because they had granted me my first glimpse into seeing film as an art-form, and not just a mode of entertainment, I decided to write him a letter.

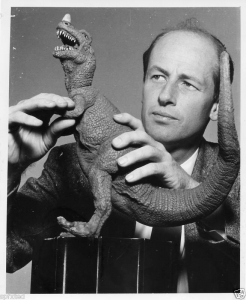

I was luckier than most kids in this endeavor, because my father was and still is an influential book editor and was able to obtain Harryhausen’s address through his publishing house. In the letters, which I wrote the summer before first grade began, I told him how much I liked his films, that I wanted to be an animator when I grew up, and even included some drawings depicting his monsters. I simply wanted to connect with the man who’d brought wonder into my life, to convey to him, in no uncertain terms, my appreciation, childlike as it might have been. Of course, in our overly critical culture some might look back and say the Harryhausen icons such as the skeletons in Jason, or his Emir from 20,000,000 Miles to Earth, or any of the other colossal creatures which graced his films, didn’t look real per se, it didn’t matter and still doesn’t. There is a suspension of disbelief necessary for appreciating a Harryhausen film, a suspension that modern audiences have become poorly practiced at, but remains important to one’s overall aesthetic health. For a child it was easy to deploy this ability, and to derive enjoyment from the visions he conjured, and so I felt a letter was the best way to express my, well, gratitude.

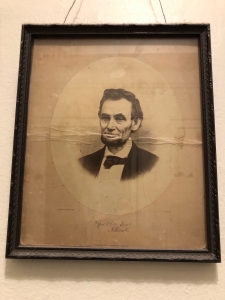

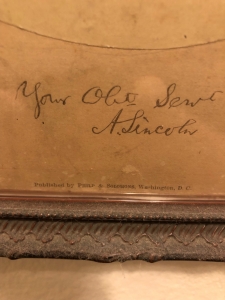

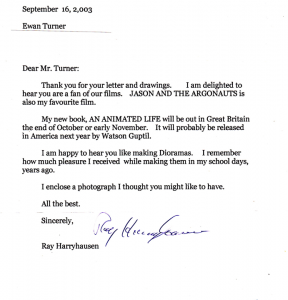

We waited a month or two, and in that time worried that the letter might have gone astray or hadn’t reached him, until finally from England, where the great man lived, a reply came, a photo of which is depicted below. I remember holding the letter in my hands in disbelief, a similar disbelief to the kind I felt when I watched his movies: utter amazement, combined with sheer joy. Reading the letter over and over, I felt I had finally made contact with someone who understood me, and who, in a sense, had freed me from the fear and worry that pervaded so much of my existence. We exchanged another letter or two over the course of the next few months, and after a time our correspondence faltered.

But it did not falter for long, as roughly a year later, my parents received word that a special “Harryhausen Night” was being held at Lincoln Center. Our eventual meeting occurred on a rainy evening in the autumn of 2004, after I had turned eight years old. My mother had discovered that for the release of his heavily illustrated book Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life (co-authored with Tony Dalton, Watson-Guptill, 2004), the man himself would be speaking and signing copies at Lincoln Center. And like a great New Yorker who knows what she wants and how to get it, she took me to meet him, and managed to get us to the front of the line.

But it did not falter for long, as roughly a year later, my parents received word that a special “Harryhausen Night” was being held at Lincoln Center. Our eventual meeting occurred on a rainy evening in the autumn of 2004, after I had turned eight years old. My mother had discovered that for the release of his heavily illustrated book Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life (co-authored with Tony Dalton, Watson-Guptill, 2004), the man himself would be speaking and signing copies at Lincoln Center. And like a great New Yorker who knows what she wants and how to get it, she took me to meet him, and managed to get us to the front of the line.

There he was: a handsome, distinguished older gentleman with fraying white hair and a round, inviting face, who in some ways reminded me of my own grandfather, a civil engineer who had his own meticulous pursuits. I remember being nervous but Harryhausen being welcoming in a way that went beyond simple politeness; he seemed genuinely touched that we’d come out to see his classic films, and touched by the nervousness we both showed. And luckily Ray and I were not complete strangers! My mother and I were sure to remind Ray—he was now Ray in my mind—that we’d had a brief correspondence. To this, he said he remembered us and that he was happy to finally meet me in person. It didn’t matter if this was true or not—for all I know he could have received hundreds of fan letters a year from kids like me—but this was all I needed to feel like I had been seen and heard and accepted.

While we stood there, with a legion of people behind us, each waiting anxiously for their own moment with him, I repeated how much I loved Jason and the Argonauts, and The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, and him smiling and saying how he appreciated my interest. He was also extremely patient as my mother attempted to take a photo of us. After several failed tries—in the picture below you can see in my eyes the fear that this moment would be lost—she managed to snap a few good ones. Ray smiled at us and signed our book and the line continued moving.

There was a screening happening in tandem with the in-person event, and soon we found our seats in the Walter Reade Cinema at Lincoln Center, settling in for a night of his classic films. Previously I had only been to the theater to see The Lord of the Rings, so this was a special night for me—perhaps one of the most special nights of my young life, and something I consider to be a personal success, though it occurred when age was still in single digits. I was having an experience that most people had not had since the sixties and seventies when his films first hit theaters and later the small screen. In fact, I don’t believe I had had such a unique experience until then, unique because I not only got to see his films in a more enjoyable setting—a great improvement over my unwieldy TV set, over which I had thrown a literal tarp—but meeting my hero in person and being touched by his genuine warmth.

There was a screening happening in tandem with the in-person event, and soon we found our seats in the Walter Reade Cinema at Lincoln Center, settling in for a night of his classic films. Previously I had only been to the theater to see The Lord of the Rings, so this was a special night for me—perhaps one of the most special nights of my young life, and something I consider to be a personal success, though it occurred when age was still in single digits. I was having an experience that most people had not had since the sixties and seventies when his films first hit theaters and later the small screen. In fact, I don’t believe I had had such a unique experience until then, unique because I not only got to see his films in a more enjoyable setting—a great improvement over my unwieldy TV set, over which I had thrown a literal tarp—but meeting my hero in person and being touched by his genuine warmth.

Later, during a break between movies, we met the actress Kathy Crosby (listed in The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad as Kathryn Grant) who starred in that film alongside Kerwin Mathews; she was lovely and down to earth and I think this was the first time I realized that actors and artists and performers were heroes, not only because they achieved the astounding feats of slaying dragons, and fencing with skeletons, and battling evil sorcerers, but because they were, just like Ray, real people. Real people, with the ability to practice a kind of cinematic magic, a shamanistic talent at making the impossible possible. The fact that Harryhausen had not forfeit the interests of his own childhood lent me hope I could participate someday in a great creative enterprise, or even make a career out of it, just as he and his lifelong friend, the renowned sci-fi writer Ray Bradbury had, whose work I was also beginning to discover.

I did not meet Ray Harryhausen again that night; nor did I meet him ever again. He passed away in 2013, long after I had garnered new heroes and new experiences. I changed schools; took up acting; picked up the guitar. My interests waxed and waned. I was drawn more to writing. But even with all the changes I went through, both mental and physical, I never forgot the person who had first made me believe in the unbelievable, who had altered my perception of the movies and made them a place where art happened and not just entertainment. He’d taught me that art, whether it be the manipulation of molded figures, or the manipulation of words on a page, or some other equally valid creative endeavor, is worthwhile and can be meaningful. Sure, you can become discouraged by the elements of creativity; you can be stymied by the logistics of plot and character; you can be interrupted in your painstaking work by a ringing phone or a director calling “Cut!”; you can be disheartened and lose interest altogether in the projects you’d previously been bound to—all that being true, Harryhausen’s lesson is one we can all learn from and take to heart. And it was that magic matters. Stories matter; they make our lives richer. To an only child who had faced some difficulty early in his life, I can honestly say that Harryhausen saved me, not only by his technical prowess, and controlled mayhem, and the delight of sharp teeth and clashing swords, but by the kindness he showed, in replying to a seven-year-old’s hopeful letter. Sometimes the best magic is the kind exchanged from person to person. Or to put it another, clearer, more perfect way: sometimes kindness is the real magic.

M. G. Turner

February 2022