One year ago today, July 15, 2023, was a Saturday. I had strapped on my helmet—and as is typical for me—taken a late afternoon bike ride around Riverside Park and the upper west side in Manhattan. As I got close to home, I rolled up to the edge of the crosswalk where W. 103rd Street crosses the northbound single-lane service road that runs parallel to Riverside Drive, and stopped to see if any cars were coming. I spotted a black car which seemed stopped at the intersection, which is marked on both sides of the road with red metal stop signs, with the same command painted in white on the pavement. I waited to see if I could safely cross to the sidewalk on the other side. There were no other pedestrians or vehicles nearby, so I gave a wave of my hand to get the driver’s attention in the black car to indicate I was going to pedal across. Unbeknownst to me, the driver had apparently only come to a rolling stop, and may not have seen my wave at him. Suddenly he hit the gas and the car began accelerating through the intersection and into the crosswalk. In fragmented milliseconds, I experienced the sinking thought, “Oh, god, he’s probably gonna to hit me. I’m glad I have my helmet on!” I pedaled harder and almost got through to the other side of the crosswalk, but the car hit me with what I think was its left front bumper. It struck me on the right side of my body and I landed on the pavement on my left side—knee, elbow, forearm, shoulder—getting dragged along the road for several feet. I had almost gotten through the intersection, but the car’s speed had overtaken me before I could get through. I think he was going about 15 mph. He definitely did not observe the stop sign,

One year ago today, July 15, 2023, was a Saturday. I had strapped on my helmet—and as is typical for me—taken a late afternoon bike ride around Riverside Park and the upper west side in Manhattan. As I got close to home, I rolled up to the edge of the crosswalk where W. 103rd Street crosses the northbound single-lane service road that runs parallel to Riverside Drive, and stopped to see if any cars were coming. I spotted a black car which seemed stopped at the intersection, which is marked on both sides of the road with red metal stop signs, with the same command painted in white on the pavement. I waited to see if I could safely cross to the sidewalk on the other side. There were no other pedestrians or vehicles nearby, so I gave a wave of my hand to get the driver’s attention in the black car to indicate I was going to pedal across. Unbeknownst to me, the driver had apparently only come to a rolling stop, and may not have seen my wave at him. Suddenly he hit the gas and the car began accelerating through the intersection and into the crosswalk. In fragmented milliseconds, I experienced the sinking thought, “Oh, god, he’s probably gonna to hit me. I’m glad I have my helmet on!” I pedaled harder and almost got through to the other side of the crosswalk, but the car hit me with what I think was its left front bumper. It struck me on the right side of my body and I landed on the pavement on my left side—knee, elbow, forearm, shoulder—getting dragged along the road for several feet. I had almost gotten through the intersection, but the car’s speed had overtaken me before I could get through. I think he was going about 15 mph. He definitely did not observe the stop sign,

I bounced up as quickly as I could manage to get away from the now idling car and squatted on the curb, hauling my damaged bike along behind me. I started inspecting my body for injuries, immediately finding a bloody knee and calf. (I was wearing shorts so my leg was scraped raw.) The driver stopped and got out of the car, presumably to see how injured I was, looking mortified at what he’d done. In a controlled but raised voice I said: “You had a stop sign, but you didn’t stop, you rolled through it and hit the gas! Do you know you did that?!” He sheepishly agreed, though he later claimed to the cops when they arrived that he had stopped at the stop sign. This was false, and in the immediate aftermath of the collision that he caused, he admitted it. Later, I learned from the guy’s driver license, issued by the state of New Jersey, that July 15 was his birthday, and he volunteered to my son that he had been looking for a parking space as he drove around the neighborhood. There is no legal parking on the Riverside Drive service road, so he wasn’t going to find a spot there.

Since I was close to home, I phoned my wife and son who were alarmed of course and said they would come right over.

While waiting for my family to arrive I called 911. When I told the dispatcher that I had been hit by a car which knocked me off my bike and I landed on the pavement hard, they said they would send an ambulance and the police.

I found that a neighbor woman had been walking by with her husband and she told me she saw it all happen. She confirmed to me what I wrote above, including that the driver hadn’t stopped, and added that she had actually seen me under the car for a moment. She gave her name and phone number to my wife and said to call her if we wanted her to speak to the police.

The ambulance arrived first so the EMTs put me on a stretcher in the back of their vehicle and drove me to Mt Sinai Hospital, at the Morningside Hts. location, while my family waited to speak with the police, or so I hoped. Had I known better—and this is the #1 lesson if you’re involved in a collision—I would have asked the EMTs if I could wait to give a statement to the police at the same time as the driver. As it turned out, the driver changed his story and lied to the cops, claiming he had stopped at the stop sign. The cops wouldn’t take a statement from my family, because they hadn’t been there at the moment of the crash, and by then, the neighbor woman had also left.

About an hour later, by which time my wife had joined me in the ER, the cops came in to to take a statement from me. By then the ER staff had put me through a full body trauma checkup and given me some painkillers. They had also put a stabilizing collar around my neck. I was laying flat on my back, a bit woozy and very uncomfortable laying there with the stiff collar which made it difficult for me to talk. They asked me what happened and I told them the driver hadn’t stopped. They told me he claimed to them that he had stopped, and it was my word against his. Through the haze I became agitated and as forcefully as I could, insisted that what he had told them was not truthful, that he hadn’t stopped, and he’d admitted that to me. I remembered the neighbor woman and they said she wasn’t there when they arrived on the scene. This ended with the cops telling me that if I wanted to, I could go to the 24th Precinct Station House to add to my statement.

The doctors decided I could go home and I was discharged without being admitted to the hospital.

I rested a lot the next few days and called a family friend who is also a lawyer. He agreed to represent me in a claim against the driver and his insurer. When I felt well enough I went to the 24th Precinct with a copy of the incident report and explained that the driver’s claim that he had stopped was false. My contention was duly noted. I added that a witness had also seen the crash, but the police declined when I asked if they would take a statement from her. Their attitude seemed to be a driver and a cyclist are on equal terms, and the latter deserves no special deference from the former, even though they’re operating a machine that weighs many multiples more than the cyclist.

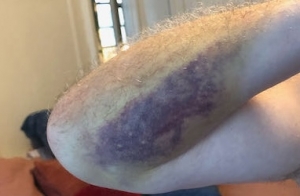

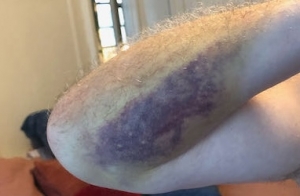

It took well over a month for the deep purple bruises, like the one on my arm shown above, to fade, and my knee was sore for months. I also had an internal problem a month to the day after the incident—I developed a kidney stone—which I thought might have been hastened or precipitated by the car crashing into me as it did, and from the resulting stress on my system. Suffice it to say, I had some health issues in the second half of 2023!

A few weeks after the crash I took my mangled bike—a sturdy Trek I had bought more than forty years ago, just as the fabled Wisconsin bike maker began selling bikes outside their home state—in for service. As is recommended after bike crashes, I also bought a new Bontrager helmet, which has a special “wave cell technology,” that is said to direct impact away from the head. and soon began riding again, albeit very carefully, with a skeptical eye cocked toward all drivers at stop signs and traffic lights. The wheels of compensation grind slowly, and a year later, we haven’t quite completed the process with GEICO. I’ll be relieved when it’s all settled.

Given the driver’s blatant disregard of the stop sign, and then his false denial of that to the NYPD, I had hoped to see the incident report revised to reflect his violation, but unfortunately that’s not how things turned out. Even without that, I’m hopeful that the claim against his insurer will be apt to raise his cost for continuing coverage, a consequence he should have to endure for his reckless driving that injured me, and could have hurt me much worse than it did. I also hope it will deter him from further reckless driving.

I’ve been riding my bike in New York City since I came here from Cleveland in 1986, and I’m happy I can say I’ve only been in the one collision over all these years. It could’ve been a lot worse, and I hope it’s the only one I’ll ever have.

-

-

All the stop signs at W. 103rd St and the service road of Riverside Drive

-

-

It was not a wide crosswalk, but the car’s speed was such that I couldn’t make it across without getting struck

-

-

My bike getting fixed.