“Poe’s Farmhouse,” a story by M. G. Turner

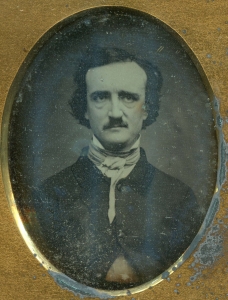

Peering through the pentagonal construction window the young writer gazed upon the barren wasteland that used to belong to one of his heroes. Poe’s farmhouse—or rather the apartment building that had once stood there—should have been designated an historical sight; yet the formerly empty structure had been flat-out demolished. There was nothing there now but rust-grey rubble and forgotten dreams—and of course a solemn-faced writer peering through the window and wondering what it must have been like for that giant of American fiction, that colossus of unhinged gothica, to have lived right on this spot.

The writer recalled his favorite stories. The Pit and the Pendulum. The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar. The Masque of the Red Death. Then he thought of the single novel that sickly scion had scribed, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym. Had all these grand, beautiful, and at times horrifying ideas gestated here? Was there something about this locale that helped engender frightening dramas to bewitch the mind and harry the senses? The air was cool and crisp; it was autumn. He peered even deeper into the mists of time, trying to discern what could not be immediately discerned. Where had the house stood? Was it there, by the empty wall, stained by rot and mold? What about the animals, if he had any? Where did they graze, where did they frolic? Where did Poe’s horrifyingly young wife find herself in the morning while her husband still slept off the inky dissolution of the night before? What about the visitors? What about his parentage? His friends? His longings? His lies? His life!

His life was here amid the stones, amid the acrid dust and shattered pebbles. His life was in the breath of the sky and in the soughing of the wind and the drizzle of the rain. A movie theater stood nearby, the equivalent of the three-penny opera of his day—the type his actress mother might have played in—easy entertainments, easy evenings, easy exigencies, as opposed to what he’d tried to compose in the dark of the night. Perhaps he had seen ravens floating up past his window or circling in the sky; perhaps birds of prey had perched upon the house in the depopulated twilight—evil portents of his young wife’s demise.

The writer thought on all of this; then his thoughts turned to himself and to his own stories which whispered to him at inopportune times. Had E. A. Poe faced the same daily struggle? Had he put off engagements, social calls, daytime explorations, nighttime ventures, all in the service of his craft? We are all in thrall to something—in some cases it is the noble work of helping our fellow man; in others it is the timeless pursuit of perfection, artistic or otherwise which makes our bones quake and our eyes water and our hearts yearn, but nevertheless answers the age-old question, the shifting, drifting dreary query the universe is always posing to, and imposing on, our six senses; the question of, what shall we do with our life?

The house was there as these thoughts and more fled through the writer’s mind. These thoughts and more consumed him, to the point where he could almost see it: a slightly dilapidated gabled home, modest in size and style, that once contained a dream. He thought of his own dreams, his own missions, his own eager anticipations. Life was moving too fast for him, the daily clip of days was maddening, he rarely took a moment to rest. But there’d be time enough to rest in the grave, time enough to contemplate the great mysteries when soil and dirt and grime had covered over the last of our remaining solidness and rendered us forgiven.

Forgiven for what? Perhaps for the sin of existing at all, for the sin of taking from the land what we could. Perhaps art is how some of us pay our rent, the metaphysical rent required of staying on Earth. Amid all of that is the urge to let go, to go mad, to exhale, to die! When the farmhouse was destroyed to make way for the next modern monstrosity, was something lost or something gained? The answer did not come to the young writer then, whose mind remained a flurry of activity. The only word that echoed in his brain as he turned from that pathetic makeshift window, that dreaded depressing spectacle was nevermore. He laughed to himself as he walked on home, thinking the hour would soon be fit for ghosts—not men.

But who was to say? If a ghost is only the shell of a man, could the reverse also be true? Could Poe’s spirit feel the same dismay at the destruction of his home as a living breathing being? Could his spirit still yearn to pace its grounds, to walk its halls, to reside inside its chambers? What about telling tales? What about weaving lies? Did the urge to create extinguish at death, like a sorry candle being snuffed? Or did ghosts seek to unfurl lays, spinning stories to each other in the tomb? What great masterpieces then have been lost to practicalities of creation? What noble dramas have only played out to an audience of spirits and shades? Do we carry on or did we cease? Do we suffer in sorrow or in peace?

To these questions and their antecedents the young writer had no answer. But he was no longer compelled to find one. For upon the heath that constituted his lost and lonely neighborhood he realized something else: he had finally broken through. He had finally landed upon that grimmest of possible isles, though the north star itself had vanished. He had entered the realm of the dead, that hallowed harbor of goodbye, and immortality was there for the taking. All he needed to do was put pen to paper, before the resplendent lights of the workaday world went forever and finally out.

M. G. Turner

New York City

October 2023