Clara Reeve: My New Literary Hero by M. G. Turner

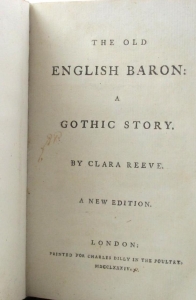

Recently I had the good fortune of making a literary discovery, which was really the discovery of a new literary hero: Clara Reeve. For those who may be unfamiliar with her work, in 1777, Reeve—an Englishwoman born in Ipswich (1729-1807)—wrote a small masterpiece entitled The Old English Baron which is a clever, exciting, and thoroughly captivating retelling of Horace Walpole’s slim novella The Castle of Otranto, written more than a decade prior. Otranto is considered as the first gothic novel and should be thought of as a seminal work. But as is often the plight of anything that is the first it is also flawed, flawed in a way that Reeve took upon herself to openly correct in her own penetrating novel that seamlessly moved the setting from rural and rugged Italy to Medieval England during the time of the crusades. The plot centers around a knight who returns to his friend’s estate after a period of war only to find that it has fallen into a state of dilapidation. It is important to note that this would become a gothic trope, beginning with Otranto and continuing with Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca—showing how time and neglect can take a piece of property formerly regal and beautiful and obscure its true nature. In this way the gothic writer laments the passage of time and does so by using style as a metaphor and trope as its device. The only difference for Clara Reeve was that she found Walpole’s novel too extreme in its many bold choices and thus tried to rectify them.

Recently I had the good fortune of making a literary discovery, which was really the discovery of a new literary hero: Clara Reeve. For those who may be unfamiliar with her work, in 1777, Reeve—an Englishwoman born in Ipswich (1729-1807)—wrote a small masterpiece entitled The Old English Baron which is a clever, exciting, and thoroughly captivating retelling of Horace Walpole’s slim novella The Castle of Otranto, written more than a decade prior. Otranto is considered as the first gothic novel and should be thought of as a seminal work. But as is often the plight of anything that is the first it is also flawed, flawed in a way that Reeve took upon herself to openly correct in her own penetrating novel that seamlessly moved the setting from rural and rugged Italy to Medieval England during the time of the crusades. The plot centers around a knight who returns to his friend’s estate after a period of war only to find that it has fallen into a state of dilapidation. It is important to note that this would become a gothic trope, beginning with Otranto and continuing with Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca—showing how time and neglect can take a piece of property formerly regal and beautiful and obscure its true nature. In this way the gothic writer laments the passage of time and does so by using style as a metaphor and trope as its device. The only difference for Clara Reeve was that she found Walpole’s novel too extreme in its many bold choices and thus tried to rectify them.

Indeed, Reeve’s conceit is one I try to take to heart myself and apply to my own writing. It is simply that when reaching out to portray the supernatural it is important not to go too far, to remain as it were on the “razor’s edge” between unbridled fantasy and stultifying reality. She recognized with the precision of a true artist something that I innately felt about Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto: it was overdone, there was too much mayhem, too much absurdity; why does a giant helmet fall out of the sky and happen to crush the groom? Why are people walking in and out of tapestries as if it were the most natural thing in the world? Why is the father, after the death of his beloved son, so instantly possessed with such lusty rage that he must attempt to marry the young man’s bride? Feeling courageous and sure of herself, Reeve tried her hand at addressing some of what she saw as Walpole’s errors. For my part, I have to admit I like Otranto just fine. But that’s just it: I like it fine. I can distinctly recall rolling my eyes at the exact points Reeve took issue with and felt compelled to explore in her own much more considered way. Reeve is an artist; Walpole is an inventor. He deserves credit for pulling together the disparate strands of style and inventing the gothic genre, but she deserves to be recognized for having written a better book, a work she herself referred to as Otranto’s “literary offspring.”

And it seems she was, in some sense, recognized for this. Though there is not much known about her life and her literary output is small—she did translations, wrote a book of poetry, and penned histories—The Old English Baron deeply offended the man she had written it in emulation of. Walpole was simply aghast than anyone, particularly a woman, would have the temerity to take his form and do something spectacular with it. Of course, both he, and later Walter Scott, claimed that her efforts were not spectacular; they put down The Old English Baron as frivolous, boring, and charmless. Walpole, in a letter to the Reverend William Cole, decreed that Reeve’s novel is: “stripped of the marvelous…, except in one awkward attempt at a ghost or two, that it is the most insipid dull thing you ever saw…” From my own perspective it is hard to see this judgement by Walpole as little more than paternalistic bitterness. Where he failed, she succeeded; where she failed, he succeeded. The two works complement each other and offer something that the other does not have; in the case of Baron a more deft way of deploying the supernatural that does not feel forced or cartoonish but instead makes you shiver with genuine fright due to its well-composed restraint; while Otranto possesses more style than its successor. Either way, these early gothic works led to Mary Shelley, to Bram Stoker, to Edgar Allan Poe, and much later, to Jorge Luis Borges. Here is a continuum that Walpole and Reeve both ushered in, and which matters in the context of our times. For the gothic has been referred to as the most “anxious” of styles and we are now in the most anxious of ages. It recognizes the innate darkness that subsumes so much of our world; estates that were once beautiful and grand can, with the passage of only a few years and within even one generation, fall into decay and utter ruin. The honor of the past is often supplanted by an insipid criminality that is always trying to get away with something. The gothic is not old fashioned, nor is it new-fangled. It is the most present of styles because it acknowledges that change is the most supreme truth of human life. All empires crumble, all families break apart. People fail to live up their promise and due to innate hubris are struck down. These are all themes that filter through both Otranto and Baron and it is our pleasure as readers—and appreciators of style—to debate which one we think did it best.

And it seems she was, in some sense, recognized for this. Though there is not much known about her life and her literary output is small—she did translations, wrote a book of poetry, and penned histories—The Old English Baron deeply offended the man she had written it in emulation of. Walpole was simply aghast than anyone, particularly a woman, would have the temerity to take his form and do something spectacular with it. Of course, both he, and later Walter Scott, claimed that her efforts were not spectacular; they put down The Old English Baron as frivolous, boring, and charmless. Walpole, in a letter to the Reverend William Cole, decreed that Reeve’s novel is: “stripped of the marvelous…, except in one awkward attempt at a ghost or two, that it is the most insipid dull thing you ever saw…” From my own perspective it is hard to see this judgement by Walpole as little more than paternalistic bitterness. Where he failed, she succeeded; where she failed, he succeeded. The two works complement each other and offer something that the other does not have; in the case of Baron a more deft way of deploying the supernatural that does not feel forced or cartoonish but instead makes you shiver with genuine fright due to its well-composed restraint; while Otranto possesses more style than its successor. Either way, these early gothic works led to Mary Shelley, to Bram Stoker, to Edgar Allan Poe, and much later, to Jorge Luis Borges. Here is a continuum that Walpole and Reeve both ushered in, and which matters in the context of our times. For the gothic has been referred to as the most “anxious” of styles and we are now in the most anxious of ages. It recognizes the innate darkness that subsumes so much of our world; estates that were once beautiful and grand can, with the passage of only a few years and within even one generation, fall into decay and utter ruin. The honor of the past is often supplanted by an insipid criminality that is always trying to get away with something. The gothic is not old fashioned, nor is it new-fangled. It is the most present of styles because it acknowledges that change is the most supreme truth of human life. All empires crumble, all families break apart. People fail to live up their promise and due to innate hubris are struck down. These are all themes that filter through both Otranto and Baron and it is our pleasure as readers—and appreciators of style—to debate which one we think did it best.

But there is something even more important in all of this, something even more topical. In this age wherein we are rediscovering voices from the past who were traditionally overlooked, neglected, or wholeheartedly ignored let us not forget the daring Clara Reeve who had the audacity to challenge a powerful man—and carve out her own not insubstantial piece of literary history; for she is the reason for the essay having been written at all! She made Walpole’s rather lurid fantasia something more profound, something that I could recognize as of a kind with greatest works of horror fiction. Because she was a woman writing in an era dominated by men doesn’t mean she should remain unappreciated. And like the ghosts which she deployed with such deftness and alacrity she can rise again, to be known as she should be known: as a pioneer of the macabre and a writer of immense talent, as fearless and brave as the champions of virtue she set down on the page.