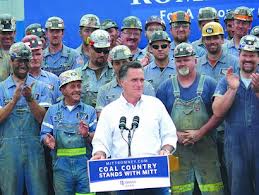

Mitt Still Using Coal Miners as Campaign Props

You may recall that a few weeks ago, I posted a blog entry, “Mitt & His Minions Sticking it to Coal Miners,” on the fact that on August 14 coal miners in Beallsville, Ohio had been compelled by their employer, Murray Energy–a company whose executives it was also revealed have contributed more than $900,000 to Republicans in the past two years–to attend a pro-Romney rally, and were docked their pay. Murray’s spox tried to deny that miners had been forced to attend the event, and offered this bizarre Orwellian statement: “Attendance was mandatory, but no one was forced to attend.” The Romney campaign used the rally for photo ops like the picture accompanying this post.

You may recall that a few weeks ago, I posted a blog entry, “Mitt & His Minions Sticking it to Coal Miners,” on the fact that on August 14 coal miners in Beallsville, Ohio had been compelled by their employer, Murray Energy–a company whose executives it was also revealed have contributed more than $900,000 to Republicans in the past two years–to attend a pro-Romney rally, and were docked their pay. Murray’s spox tried to deny that miners had been forced to attend the event, and offered this bizarre Orwellian statement: “Attendance was mandatory, but no one was forced to attend.” The Romney campaign used the rally for photo ops like the picture accompanying this post.

Now, TPM is reporting, as is the Columbus Dispatch, that the Romney campaign has released two new TV ads, again using the rally with the miners as the backdrop for their bogus claims that the Obama administration is “waging a war on coal.” I can’t imagine the ads are going to do their campaign much good, with them inevitably trailed by reports of the tainted rally at the coal mine.

Please note a few more things about Bob Murray, CEO of Murray Energy.

1) He is a vociferous denier of global warming who claims that scientists are trying to make money off climate change. That’s rich–a guy who’s made his own fortune digging and shipping coal is accusing other folks of trying to cash in on cleaning up his mess. Think Progress’s Stephen Lacey has reported Murray said:

“The fraudulent individuals around the world who have attempted to capitalize on the promotion of their theory that the Earth is warming are now finding out that it’s just not true. . . . They did it for what I call crony capitalism – to make money off global warming. . . . Albert Gore has made hundreds of millions of dollars over his hoax, and now they’re finding it’s simply not true.”

2) In the same item, Stephen Lacey reports,

“Murray Energy is perhaps best known for operating the Crandall Canyon mine in Utah that collapsed in 2007, killing six miners and two rescue personnel. After that tragedy, reporters uncovered thousands of violations resulting in millions of dollars in fines at various mines owned by the company.”

3) According to an item by media reporter Jim Romenesko, last month Bob Murray sued Charleston Gazette (WV) reporter journalist Ken Ward, Jr. for supposedly defaming him. Ward had written:

“’Renegade coal operator Bob Murray played a major role recently in a campaign fundraiser in Wheeling, W.Va., for Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney’” and that ‘the question for Governor Romney, of course, is whether he thinks criminal behavior by coal companies, especially when it kills workers and damages the environment, is acceptable. If not, why is he buddies with Bob Murray?’”

I hope Ken Ward, Jr., and his newspaper don’t have to spend a fortune in defense of his First Amendment rights.

//end//