Proud to Have Been a Judge for the J. Anthony Lukas Prize Works-in-Progress Awards, Announced Today

May 1, 2024—I received this message from administrators of the Lukas Prize at Columbia Journalism Graduate School regarding the ceremony scheduled for May 7 to honor the recipients of the awards:

“Out of an abundance of caution and with deep regret, we have decided to cancel this year’s Lukas Award Ceremony. With the volatile circumstances on campus, we feel it is in everyone’s best interest to delay this celebration until a later date when we can properly honor the winners, and thank you for your stellar work in judging these prizes.”

—

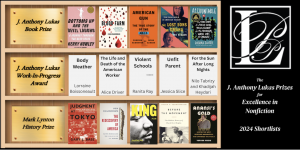

Since early fall last year, I’ve been serving as one of three judges for the Works-in-Progress Awards of the J. Anthony Lukas Prizes, sponsored by the Columbia Journalism School and the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard. Collectively, we read nearly 100 nonfiction book proposals and mission statements submitted for consideration, with each of us reading approximately one-third of the entries, then arriving at a shortlist of fifteen titles, which was announced last month.

Since early fall last year, I’ve been serving as one of three judges for the Works-in-Progress Awards of the J. Anthony Lukas Prizes, sponsored by the Columbia Journalism School and the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard. Collectively, we read nearly 100 nonfiction book proposals and mission statements submitted for consideration, with each of us reading approximately one-third of the entries, then arriving at a shortlist of fifteen titles, which was announced last month.

Following more discussion among the three of us, we chose two works-in-progress—whose authors will each receive $25,000—which have been announced today. The works-in-progress awardees are Body Weather: Notes on Illness in the Anthropocene by Lorraine Boissoneault (Beacon Press), which was in my original tranche of proposals, and The Life and Death of the American Worker: The Immigrants Taking on America’s Largest Meatpacking Company by Alice Driver (One Signal, Atria).

Here are the citations we wrote for the books:

Body Weather is a visceral work of reported essays, masterfully braided with narrative research. Lorraine Boissoneault tells the story of living with chronic illness at a time when the planet is in a state of dire suffering. Climate change is bringing more hurricanes, lightning, tornadoes, fires and landslides. How will a distressed planet affect stressed, ill or disabled bodies? In poetic and haunting prose, Boissoneault unearths intersections between her unique experience living with illness, while also illuminating universal questions lodged within all of us: How do we learn to live with discomfort? “How do we seek refuge from our own bodies, from weather that wraps itself around the world?” The Lukas Prize will enable the author to travel from her home base in Chicago to the Saguenay fjord in northern Quebec, to Death Valley in California and to Australia’s outback to complete reporting for the book. Body Weather is a singular work of literary reportage, a firsthand, intimate account drawing profound connections between the body and the planet.

The Life and Death of the American Worker is a rigorously researched work of narrative nonfiction that exemplifies the spirit of holding powerful institutions accountable, while humanizing the individuals who have been systematically dehumanized by immigration law and unregulated labor practices. Powerful forces have tried to silence the project and the people who are part of it. Yet with deep access and empathy, Alice Driver tells the multifaceted stories of families who have filed a class-action lawsuit to hold Tyson responsible for the working conditions that caused the deaths of their loved ones. She conducted interviews in the various native languages of subjects, and the Lukas Award will go toward some of those translations. Although many journalists have held temporary jobs within meatpacking plants to write about the industry, Driver (who is from Arkansas and grew up around Tyson employees) is solely focused on the longterm experiences of immigrant workers who have been at Tyson for decades. Driver has performed a remarkable feat of investigative and narrative reporting in telling the stories of these essential yet often overlooked and exploited workers.

It was a pleasure to serve with my fellow judges, Chris Jackson, Publisher and Editor-in-Chief, One World Publishing, Penguin Random House, and Erika Hayasaki, Professor at the University of California, Irvine, in the Literary Journalism Program, and author of Somewhere Sisters: A Story of Adoption, Identity and the Meaning of Family (Algonquin Books, 2022). I also want to thank publishing friend Peter Ginna, who had been a Lukas juror in previous years, who recommended me for this assignment. I’m also grateful to Program Manager of Professional Prizes at Columbia Journalism School Susie Marples for her deft and genial handling of many matters.

I want to add that a great majority of the projects submitted to us were worthy of support and consideration. In the course of our deliberations, on many occasions one of us said to the others, “I wish we could recognize and support all these books!” As an affirmation of that reality, the graphic with this post shows the fifteen books shortlisted for all Lukas Prizes this year, including the five works-in-progress.

The J. Anthony Lukas Work-in-Progress Awards are given annually to aid in the completion of significant works of nonfiction on American topics of political or social concern. These awards assist in closing the gap between the time and money an author has and the time and money that finishing a book requires. J. Anthony Lukas (1933-1997) was the author of many books, including Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families (Knopf, 1985), which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

Two other Lukas Prizes were announced today:

Accountable: The True Story of a Racist Social Media Account and the Teenagers Whose Lives It Changed by Dashka Slater (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, August 2023), the J. Anthony Lukas Book Prize ($10,000).

A finalist for this prize was also recognized: Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs: A Journey Through the Deep State by Kerry Howley (Knopf, May 2023)

and

The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History by Ned Blackhawk (Yale University Press, April 2023),

the Mark Lynton History Prize ($10,000)

A finalist for this prize was also recognized: Judgment at Tokyo: World War II on Trial and the Making of Modern Asia by Gary Bass (Knopf, October 2023)

Congratulations to all the authors, as well as their editors and their literary agents! There will be a public ceremony on May 7 at the Columbia Journalism School, honoring all the authors and their work.

From the prize website: “Established in 1998, the J. Anthony Lukas Prize Project honors the best in American nonfiction writing. Co-administered by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard, and sponsored by the family of the late Mark Lynton, a historian and senior executive at the firm Hunter Douglas in the Netherlands, the Lukas Prize Project annually presents four awards in three categories.”