Readings from “Rust Belt Chic” at Vol. 1 Brooklyn Reading Series

New Year’s Day I began to feel creeping over me one of the viruses that’s been forcing so many people to their beds. Day One’s utter tiredness soon morphed into a stomach bug. After three semi-miserable days, by Thursday night, Jan. 3, I was finally well enough to venture out of the apartment. I’d been building myself up to enough of a rally that I hoped I could manage at least a couple hours out in public. I was scheduled to be among the readers at a long-planned night of readings from Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology, to which I’d contributed, “Remembering Mr. Stress, Live at the Euclid Tavern.” I’d been looking forward to it since RBC co-editor Anne Trubek asked if I wanted to be part of the event. What’s more, I’d invited friends who said they’d be there–I couldn’t not show up. Still, not feeling good yet, I let Jason Diamond, host of the reading series Vol. 1 Brooklyn know that I’d been ill and asked if he could slot me in early on the program, in case I had to bail or something. He was great about it, putting me first. I appreciated this. I used to often speak up first in classes, and have never minded being in that spot.

The reading room at Public Assembly in Williamsburg, Brooklyn was a big darkish space with rows of folding metal chairs, some upholstered benches, and lights above and behind a wide stage on one side. Jason introduced the program by revealing his geographic own roots–not Cleveland but Chicago. He said that to a kid like him growing up in Chicago–while parts of the nearby Midwest clearly identified with something: Minnesota=hockey; Wisconsin=the Packers; Detroit=the Pistons, who Bulls fans hated–about Cleveland–even less was certain. It struck me that while Chicago may have its widely reputed Second City issues, it’s always the First City of the Midwest. After Jason read the brief bio about me that I’d provided, he brought me up to the stage. As I set my talking script on a music stand next to the mic I looked out across the chairs and found I couldn’t see anything or anybody. Those lights above the stage were now all behind me, leaving me peering in to a black cavern. I was a bit unsettled, not having presented somewhere like this before. When I speak, say, at a publisher’s sales conferences, I rely on eye contact with the book reps to know how my points and pitches are landing. I had some lines in my script I hoped would prompt a few laughs, or a tear, but the delivery was going to be tricky under the circs. No problem, I thought, I know people are still sitting there, even if I can’t see anyone. With that, I launched in to the piece:.

Growing up in the hotbed of rock n’ roll that was Cleveland in the 60s and 70s, I began going to hear live music before I had even turned fourteen.

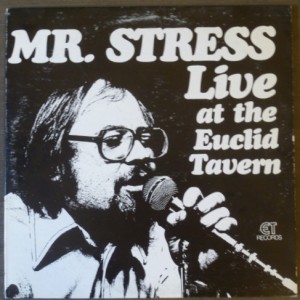

This was exciting. I could feel confidence growing in the crowd that they were going to be hearing something interesting. Their interest seemed to grow as I read and talked the piece over the next six minutes. At about the midpoint, I revealed a visual aid I had brought–my copy of the album that gave my essay its name, “Mr. Stress, Live at the Euclid Tavern.” This drew an appreciative titter from the crowd. I wrapped up with these two graphs:

In reporting this piece, I interviewed Cleveland musician Alan Green, with whom Stress played live gigs as late as 2010. He reminded me that Stress was born a minute after midnight on New Year’s Day in 1943, and was feted as Cleveland’s firstborn of the new year—a fitting birth for a bluesman if you remember bluesmen singing the lyric about the fabled character, “born the 7th son of a 7th mother on the 7th day.” Clearly, Stress had a suitable pedigree for a bluesman. Alan’s reminder that Stress had long ago been a New Year’s baby brought back a flood of rich memories from great New Year’s Eve shows when Stress and revelers raucously marked a new year and Bill’s birthday.

Living in New York City today I remain a devotee of going out to hear live music, a happy habit I formed forty years ago listening to Mr. Stress. I must add that after Rust Belt Chic was published last fall, Stress read my essay and we’ve been reunited via telephone and the Internet, after more than 25 years being out of touch. He’s very glad to see his career remembered in this book. Even with macular degeneration, he still reads voraciously with the aid of voice-enabled software. We were in touch on his birthday two days ago, his 70th, and he knows I’m presenting his story here tonight.

I felt good delivering this tribute. It was mete and right to honor Mr. Stress who warrants more homage and notoriety for having given so much to the blues and Cleveland’s live music scene over many decades. As I added for the crowd, Stress’s impaired vision may be at least partly attributable to his music-making, for he told a Cleveland Plain Dealer reporter in 2011,

“I woke up one morning and. . . I had lost a third of my vision. I’ve heard it comes from [a harmonica player] blowing so hard, you pop blood vessels. I can’t drive or get around as well. But it ain’t stopping me from playing the blues.”

As I finished I glanced up from my pages and looked into the darkness. A soft “Whew” and a whistle came from the audience, then an uprush of clapping. I was amazed at how long the applause lasted, seeming to go on for many seconds. I couldn’t have asked for a more attentive audience, or a more appreciative reception.

I was followed by six other readers, five of whom were contributors to Rust Belt Chic, all former Clevelanders, and one guest Michigander, who told a story about Detroit. It was a grand night, made grander by the boisterous crowd, easily more than 50 people–this, only three nights after New Year’s Eve–Jason Diamond‘s inspired MCing; and stellar presentations.

The order in which the seven of us read, from last to first is pasted in below, with our bios as they were provided to Jason, readers’ relevant links, and a brief note on the topics each of us presented. I made an audio recording and if I’m able, will later share my reading on Mr. Stress. I want to thank certain friends who came to the event: Bridget Marmion, of Your Expert Nation, a book marketing firm with which I am also associated ; Daniel Zitin, independent editor, and his son Benjamin; and Peter Ginna and George Gibson, of Bloomsbury Publishing (they are also colleagues with RBC contributor, Pete Beatty, who was the evening’s last reader.). Copies of Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology were sold that night, and you can buy it too, from Cleveland-area retailers, online booksellers, and the RBC website. I urge you to support this unique expression of community literary spirit.

Meantime, if you want to read my essay pretty much as I delivered it Thursday night, please find it at the post below this one here on The Great Gray Bridge. You may also click on this link for the complete post with photos, the contributor bios and their topics of discussion.