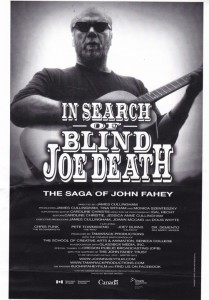

“In Search of Blind Joe Death,” New Documentary on John Fahey

Intv’w abt new doc on guitarist John Fahey from @LeonardLopate show-http://t.co/WRJ0JF1Nmp NYC screening tonite w/director @JamesCullingham

— Philip Turner (@philipsturner) August 16, 2013

After hearing filmmaker James Cullingham interviewed on WNYC last Friday I was glad I could make it to Cinema Village that night for the first Gotham screening of “In Search of Blind Joe Death,” Cullingham’s new film on John Fahey, the idiosyncratic instrumental musician, fabulist, record label founder, album hunter, turtle venerator, musicologist, and writer who pioneered a genre dubbed around 1960 as “American primitive guitar.”  Along with the poster for the film, also shown here is a shot (courtesy of docnorthfestival.ca) showing Cullingham (r.) with Pete Townsend of The Who. Ever a literary-minded sort, Townsend, a former book editor, says in “Joe Death” that for him Fahey occupied a role like that played by William Burroughs or Charles Bukowski in modern American literature.

Along with the poster for the film, also shown here is a shot (courtesy of docnorthfestival.ca) showing Cullingham (r.) with Pete Townsend of The Who. Ever a literary-minded sort, Townsend, a former book editor, says in “Joe Death” that for him Fahey occupied a role like that played by William Burroughs or Charles Bukowski in modern American literature.

As suggested by Townsend’s reference to the Beats, Fahey drank and over-used prescription meds. Sadly, he also suffered with diabetes and other chronic ailments. His life journey was at times lugubrious and he was living quite squalidly when died at age 61, but the film does a very good job of spotlighting his considerable talents and singular accomplishments for which we should be grateful. He developed a prodigiously creative vernacular guitar and compositional style that reflected blues, folk, and traditional American sources while also drawing on Charles Ives, Bela Bartok, Gregorian chant, and world music, before that term had any currency. As a facilitator and label owner, he would do things like send a postcard cold to a black bluesmen c/o General Delivery at a Mississippi delta town post office where he hoped the man still lived, asking: “Would you like to record for the Takoma Records label?”; thus, did he bring to public awareness the music of Booker (later known as ‘Bukka’) White. He was also involved in rediscovering Charley Patton, Skip James and more guys with “Blind” as part of their name than I’d ever known of.

Before his death in 2001, Fahey would himself be rediscovered by grunge bands, including Sonic Youth and Cul de Sac. Along with Townsend, Cullingham also interviewed Chris Funk of The Decemberists and Joey Burns of Calexico, both of whom testify to Fahey’s influence on their music. I met the filmmaker briefly before the screening and I learned he worked for a time at the CBC. He lives in Toronto, and is associated with Seneca College there. In his interview on the Leonard Lopate Show he said that he met Fahey three or four times when he performed in Toronto. Although the guitarist had a deserved reputation for making up stories about himself and his origins, with flights of fancy that were expressed in colorful titling of his compositions and prolific self-mythologizing, the director said he always found Fahey straightforward and direct. Blind Joe Death, borrowed by Cullingham for his title, was one of Fahey’s album names and one of the aliases he adopted as a creative alter-ego, mordantly observing that if a musician had “blind” and “death” in his name he would surely be successful.

Lots of archival sequences of Fahey talking and playing are punctuated by the interview segments with a total of about eight music industry figures (including Townsend, et al). There’s also conspicuous use of animation in the film, with many of the graphics arriving on-screen in sequentially hand-lettered script. This was used to best effect when the filmmaker’s voiceover reads the contents of Fahey’s postcard to Booker White in Mississippi. The audience chuckled at that on-screen animation as it unfolded for all to read along with the voiceover. According to the wikipedia article on Fahey, the White album then released on Takoma became the label’s first non-Fahey release.

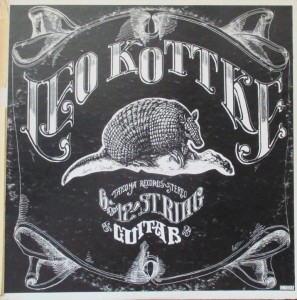

Takoma was far from a vanity enterprise. Among the artists and acts Fahey championed on the label were guitarist Mike Bloomfield and Canned Heat, both of whom I recently saw on-screen in the blues documentary “Born in Chicago“, and Leo Kottke, whose first album “6 and 12-String Guitar,” released in 1969, is still a treasured part of my record collection. It became Takoma’s single bestselling release. From the armadillo on the cover (not a turtle, but here you might say a hard-shelled repti-mammal stands in for the standard reptile), through Kottke’s liner notes and the song names on the back of the album below, you can see that he had fun borrowing Fahey’s grandiloquent style and self-mythologizing. (“All that is left to be said is that Kottke’s voice does not appear on this album. His guitar does.”)

Though Fahey’s life took downward turns in later decades, he nonetheless managed to start a second label, Revenant Records; in 2003 their Charley Patton CD collection won three Grammys. The name revenant could not have been accidentally chosen, suggesting an unkillable being who returns from beyond to seek revenge against his tormentors; perhaps Fahey saw himself in pitched battle against dumbing-down influences and the homogenization of indigenous cultures. There is no readily distilled or uplifting message in Fahey’s life, yet I recommend the film for showing how a determinedly idiosyncratic and protean artist may make a musical mark and leave behind a rich legacy of inspired experimentation and curation. To learn more about “In Search of Blind of Joe Death,” I suggest you listen to Leonard Lopate’s interview with James Cullingham from August 16 and visit the film’s website to learn about future opportunities to see it.