The Story Behind a Handsome New Book on Books

The Story Behind a Handsome New Book on Books

One bright spot during the dark first year of COVID came on October 10, 2020, almost three years ago. I was invited by Buz Teacher to write an essay for a book he was assembling, an oral history of bookselling and publishing in the last century. Buz had asked my publishing friend Mildred Marmur for a contribution to the forthcoming book and she advised him to ask me, too. Given that I’d been writing about writing about both subjects for more than a decade it didn’t take me long say yes.

Fortunately, I had about six months before I would have to deliver my essay. As is my wont when I have a writing assignment that I’m obliged to deliver—this is true for writing pitch letters as an agent, or when I was an in-house editor in publishing companies and I had dust jacket copy and catalog copy to write—I fretted about it for some time without actually writing anything. I couldn’t think how I might start it. Eventually I did quit procrastinating and found a place to begin.

I handed the essay in, in June 2021, under the title “The Education of a Bookselling Editor,” clocking in at approximately 4100 words. I welcomed the opportunity to write longer than usual; personal essays on this site, like one I published here—about working with William Styron on an Introduction he wrote for Dead Run, a nonfiction narrative I edited about an innocent man on Death Row—tend to less than 2500 words.

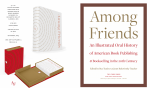

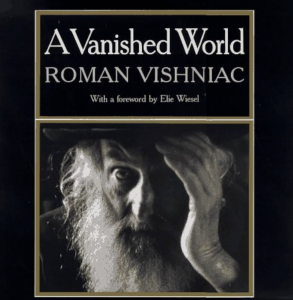

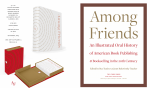

I also handed into Buz, and his co-editor, his wife Janet Bukovinsky Teacher, about half a dozen photos and illustrations from Undercover Books, the bookstores I ran with my siblings and our parents at the start of my career, and from some of the titles I’ve brought out as editor, which they said they hoped to use as they laid the book out. For more than two years, I’ve been wondering which ones they might use. Much time passed, but Buz kept in touch, and I had faith that the design and production of the book, and all that was necessary to make what would ultimately be a 576-page tome—the impressive volume is 9 inches wide, 11 inches tall, with a 3-inch thick spine, and weighs about nine pounds, with dozens of photos and illustrations and essays by more than 100 contributors (many of whom are bookpeople I know)—was well in hand. My confidence wasn’t misplaced—after all, Buz and his late brother Lawrence had co-founded the indie publisher Running Press back in the day.

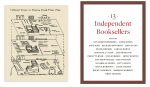

Contributors were not being offered money as payment, but Buz promised us all a finished copy of the book, which I’m thrilled to say arrived today. This is the book’s website, where there’s a two-minute video trailer. The official publication date is in two days, September 23rd. They edited my piece lightly**, and split it into into two sections; one, headed Independent Booksellers: All in the Family, is devoted to my years as a bookseller with Undercover Books, the bookstore I founded and ran in Cleveland from 1978-85 with my siblings Joel and Pamela, and our parents, Sylvia and Earl; the second, called Literary Independents: Making a Difference, covers roughly my first two decades as an in-house editor and publisher.

As the book copy puts it,

“In lively personal essays about the people, companies, and books that helped shape our culture, more than 100 prominent figures and publishing and bookselling recall their careers during a time of extraordinary growth, from the postwar period through the revolutions of the 1960s and ’70s to the new millennium. Illustrated with original photography of vintage book jackets, period graphics form Publishers Weekly and archival photos, Among Friends reveals how the book industry both reflected and responded to societal changes. This deluxe limited edition pays homage to the creative and entrepreneurial spirt of that time.”

If you’re a bibliophile or if you have a book collector on your holiday gift list, I suggest you consider buying this very special book for them. They only printed around 1600 copies, so if this is a book for you, or someone you love, I suggest you not wait to buy it, because it could sell out, and the price of it in future resale is in my opinion likely to rise in years to come beyond it’s published list price of $200.

Below is the complete essay I wrote in 2021, and below it are photos of the handsome book and the hinged box and my contributions to it. It is really a stunning book.

—

The Education of a Bookselling Editor

Founding Undercover Books

In 1977, while finishing my last year as an undergraduate at Franconia College, an experimental institution in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, I had intended with my bachelor’s degree in history of religion and philosophy of education, to seek a professional niche for myself promoting interfaith dialogue among Jews and gentiles. I hoped to work for an organization with a mission to combat bigotry, anti-Semitism, injustice, and intolerance. After returning to Cleveland, my hometown, I began looking in this direction, but quickly learned that, lacking an advanced degree, I was unlikely to have a chance of getting anywhere in the field. What’s more, as an émigré from traditional education—I had also attended an alternative high school, my first happy immersion in the educational ferment of the times—graduate school was the last thing I wanted to do! I may have only known it inchoately, but I sought a field in which my nontraditional education and interests would not hold me back, and might even propel me forward.

At roughly the same time, my elder siblings, out in the work world longer than I, were already plotting exits of their own from any chance they’d be relegated to humdrum working lives.

Pamela, the eldest of us three, had worked in Cleveland’s grand department stores, which had bustling book departments, and middle sibling Joel (d. 2009) had worked at Kay’s Bookstore, in downtown Cleveland, a venerable book emporium whose truculent owner Rachel Kowan kept her employees on their toes by challenging them to answer exactly where certain titles in the rambling three-floor store were shelved, along with other tests of arcane bookselling knowledge, such as which edition of Goethe’s Faust contained Parts I and II of the frequently abridged work.

Pam and Joel’s smart idea was to open, with our book-loving parents Earl and Sylvia, a new bookstore in Shaker Heights, the suburb where we’d grown up. I quickly tossed my lot in with them, at least to get the store opened, then soon found myself more involved and engaged by bookselling and the book business than I’d anticipated. We chose the name Undercover Books—invoking our passion for reading under the covers as kids, and for mystery fiction—and on May 4, 1978 opened the first of what would ultimately be three locations.

In this collection of essays about bookselling and publishing in the second half of the twentieth century, it is noteworthy that Undercover Books joined the wave of a building trend in the 1970s-80s in which retail bookselling was migrating from department stores and big downtown bookstores to indie bookstores in the suburbs of a number of cities—Pittsburgh, Detroit, Atlanta, St. Louis, Kansas City, as well as in our own downtown, where many local readers had long shopped at Publix Book Mart, run for decades by the eminent Anne and Bob Levine. However, suburbanites with readerly interests not inclined to visit downtown were under-booked, it could be said.

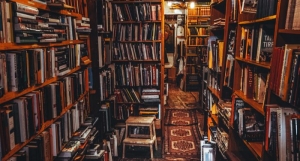

The space we leased in an outdoor strip shopping center—deliberately not an indoor mall—had formerly housed a shoe store where we’d shopped as kids, and was large at 2700 square feet, but the shape itself was that of a shoebox, and could’ve made for a very dull bookstore layout. Smartly though, a store designer showed us how to address this problem: beyond the front section of the store, where the cash counter and walls of bookcases displaying lots of frontlist fiction and nonfiction were displayed face-out, we could cut into the rectangular space with wooden bookcases built at 30-degree angles, lending an intimate, library-like feel to the store. With that, the Travel, Reference, Literature, Poetry, Art & Photography, Children’s, Health & Parenting, and Cookbook sections became their own quiet spaces. The opening of this attractively designed bookstore, in a suburb with a well-educated populace that had never had a bookstore within its city limits, quickly attracted the trade and appreciation of lots and lots of people locally and in the city more widely.

I enjoyed working on in-store displays, and grew adept at fashioning arrangements of books that encouraged browsers to make connections among titles, subjects, authors, and ideas, while also managing to shelve the greatest number of titles possible in finite spaces. As adult book buyer, I ordered books that led to annual sales exceeding $1,000,000, at a time when that level of sales was not common among independent bookstores. Regularly called upon by sales reps, and pitched specific titles by sales management, Undercover Books became a go-to store for publishers eager to break out books nationally. Notable fiction writers who launched books with us included Mark Helprin (A Dove of the East, and Other Stories, Seymour Lawrence/Delacorte Press), Richard North Patterson (The Lasko Tangent, W.W. Norton), and Walter Tevis (Queen’s Gambit, Random House). We also held salon-like evenings, as when George Gibson of David R. Godine, Publisher, discussed the Godine list and fine printing with our customers.

We’d look for books we had already read and enjoyed, new or backlist, on which we would take aggressive ordering positions, then sell 300-400 copies of these titles in a two- or three-month stretch. This happened with Simon & Schuster’s trade paperback reissue of Jack Finney’s classic time travel novel Time & Again, as it did with the travelogue Blue Highways, when author William Least Moon was brought in by our Little, Brown rep to meet us and sign stacks of the hardcover we had ordered. Our parents were also avid readers, Sylvia of commercial fiction and cookbooks, Earl of biography, sports and business, and their enthusiasms meant our in-store selection appealed to a wide age range of readers. Our parents also opened their home for meals and convivial time with sales reps and authors.

Cleveland was the home of many Fortune 500 companies, and most had corporate libraries in their home offices, where professional books were often required, likewise true of partners in remote offices who also needed books for their work. We worked with staff librarians who got requests for books for the home office and from distant branches, all of which business we’d fulfill. We made rapid delivery of special orders and prompt service on bulk orders of business books, reference titles, and professional manuals a priority. Innovations we made in book ordering and inventory management, in conjunction with book industry expert Leonard Shatzkin and his son Mike, a publishing consultant, made Undercover Books the subject of a chapter in Leonard’s diagnosis of the book business, In Cold Type: Overcoming the Book Crisis (Houghton Mifflin, 1982) and of articles in Publishers Weekly.

In this period, Joel became a board member of the American Booksellers Association (ABA), which gave us a voice in independent bookselling’s response to the growing influence of corporate chain bookselling. Able to start a conversation with just about anyone, Joel enjoyed public organizing and in 2000 ran for the House of Representatives in Ohio’s 11th congressional district. That same year, Pamela was hired by Overdrive, an early distributor of ebooks. With responsibility to uphold copyright, publishers wanted assurance that their titles would be secure on the emerging platforms. As director of content, she worked to gain the confidence of sales and marketing departments, holding that position till 2004, a key period in the digital transition.

During my time in bookselling I read avidly in all genres of fiction, especially many detective series and spy fiction, enjoying and recommending books by George Chesbro, James Crumley, Earl W. Emerson, Dorothy Hughes, Margaret Millar, Russell Greenan, John Le Carré, Tony Hillerman, Ross Macdonald and John D. Macdonald. We also had great clientele for new literary fiction, selling many copies of books by Robert Stone, Brian Moore, Peter De Vries, Anne Tyler, Barbara Pym, Margery Sharp, Margaret Atwood, Laurie Colwin, Howard Frank Mosher, Ernest Hebert, and Susan Richards Shreve.

It should be noted too that we opened just as a new generation of Canadian authors was bursting in to print, and I had an instant affinity for Canadian literature. Though trade rules at the time discouraged importation of Canadian titles, I found a way to work around them. Seal Books was Bantam Books’ Canadian division; their titles resided ostensibly off-limits to us on an out-of-the-way corner of the Bantam order form. Our Bantam rep instructed me if I ordered any Seal Books titles the order wouldn’t be filled, but I penciled in some quantities to see what would happen, and they were shipped to us! We began introducing our customers to books by Margaret Atwood, Mordecai Richler, Margaret Laurence, Marian Engel, Antonine Maillet, Alice Munro, Guy Vanderhaeghe, Timothy Findley, Farley Mowat, Pierre Berton, the longtime CBC broadcaster Patrick Watson, who visited our store to launch his suspense novel, Alter Ego (Viking, 1979), and Robertson Davies.

We were ordering Davies’ Deptford Trilogy (Fifth Business, Manticore, World of Wonders) by the carton from Penguin, stacking them up and selling them in large quantities. In my enthusiasm, I wrote Davies a letter c/o of Penguin to explain this and let him know about our stores. A pleasant correspondence ensued between us, his letters from which are reproduced in facsimile form here.

In 1982 Davies’ editor at Viking, Elisabeth Sifton, invited me to write a letter to U.S. booksellers extolling his work and pitching them on his new novel, The Rebel Angels, which became the Canadian author’s first U.S. hardcover bestseller.

The bookstore was graduate school for me. After seven years, I felt the proverbial itch and decided I’d like to try working in publishing, preferably as an editor. I was keen to originate books, not just sell them as finished products, and with the bookstore experience, I was hopeful I could get a job and do meaningful work. In 1985, I embarked for New York City and bearing in mind E.B. White’s observation in his essay “Here is New York” that, “No one should come to New York to live unless he is willing to be lucky,” I found an apartment in Washington Heights, the hilliest section of Manhattan with its bike-able hills and steep stairways, and the dramatic George Washington Bridge in view from many vantage points, endowing me with a fondness for bridges that lasts to this day as evidenced by the name of my book-focused blog, The Great Gray Bridge, an homage to the 1942 childrens classic The Little Red Lighthouse and The Great Gray Bridge.

Following my departure from Cleveland, the family continued operating from the original location, and then in 1992, to capitalize on the strong B2B elements in the business, Joel re-envisioned the business as Undercover Book Service, supplying books to individuals and corporations all over the country and abroad. With the emergence of the Internet in 1993, the family transformed the stores into an online book-ordering service powered by a website they created some months before Amazon got underway.

Turning 7 Years of Bookstore Experience into a Publishing Career

One of the first publishing houses I applied to was Charles Scribner’s Sons, as the firm now called Scribner was then known. A contributor to this volume, Mildred Marmur, was its president then, the first female head of a major house. Though we’d never met, she saw me in her office. Intrigued by my background, she explained she had nothing full-time to offer me, but added that the company was sponsoring a first novel contest named after Maxwell Perkins, the legendary Scribner editor who’d nurtured the talents of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and James Jones. She asked if I’d want to work as the contest’s first reader. I told her that at Undercover Books we’d sold A. Scott Berg’s biography, Maxwell Perkins: Editor of Genius (Dutton, 1978), so would be pleased with the opportunity to tap into Perkins’ literary legacy.

More recently, it must be said that as I’ve been preparing this essay for print, I’ve learned about a different legacy of Perkins’ that does not shine favorably on him or Scribner: his shameful elevation of eugenics through their book list, a revelation from author Daniel Okrent that has led to an overdue re-assessment of the Scribner editor’s reputation by many, including the editor of Penguin Random House’s One World book imprint, Chris Jackson, the 2020 recipient of an award formerly given in Perkins’ name. To me, this shows that our business should never be satisfied with its past, but in concert with the wider society, must always work toward a better future for all.

Working three days per week in what ended up as a two-month stint in the winter of 1986, I ensconced myself in Scribner’s conference room with unopened jiffy bags and manuscripts stacked up around me like so much drying cordwood. Think John Updike’s classic sketch “Invasion of the Book Envelopes.” My assignment was to unpack the mailers and read between 5-50 pages of each manuscript of what turned out to be more than 700 contest entries. I also filled out a brief questionnaire, signaling a thumbs-down or -up for a second reading by senior editors. Coincidentally, I recommended seventy entries, or almost exactly 10%, for second readings. There was one entry I really loved, by an E.M. Hunnicutt, which I read avidly beyond the allotted limit. My recommendation of it was more enthusiastic than for any other candidate, but before I’d finished plowing through all the entries, I saw that it wasn’t going to win the prize. I noted the author’s phone number and address and photocopied the manuscript, hoping I might contact “Hunnicutt” soon, once I was hired somewhere as a full-fledged editor.

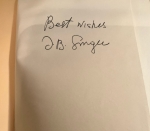

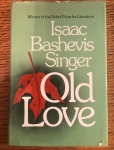

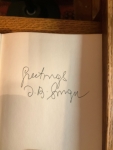

My good luck held and soon, after a reference from literary agent Ruth Nathan (wife of longtime Publishers Weekly subsidiary rights reporter Paul Nathan), I was offered a job as an acquiring editor at Walker & Company, a somewhat sleepy publisher of young adult non-fiction and genre adult fiction (Westerns, mysteries, Regency romances, etc.), published mostly for libraries. Walker had terraced offices with scenic views twelve storeys above Fifth Avenue at 56th Street; on St. Patrick’s Day the company threw parties as the annual parade streamed past below, attended by house authors such as Isaac Asimov. I was assigned the genre that founder and publisher Sam Walker called “men’s adventure”–thrillers, swashbucklers, seafaring novels, spy books, a genre I still enjoy. Walker had in its early years published books by John Le Carré and Flann O’Brien, so I was hopeful that my mandate might extend to other areas of publishing, even literary fiction. My first week at Walker I called E.M. Hunnicutt—whose initials made me think of E.M. Forster—and learned that E.M.’s first name was “Ellen.” She explained that because she sold many stories to Boys’ Life, the magazine of Boy Scouts of America, she’d long used the initials to disguise her gender,

Ellen and I hit it off beautifully and for an advance of $750 I acquired rights to her novel, the first novel I line-edited. Our relationship established a high benchmark in my relationships with authors that I’ve always sought out since. Ellen and I engaged in a vigorous dialogue about her work and its dominant theme—the creative purposes to which suffering and mourning may be put. The protagonist of the novel was Ada Cunningham a young teenage girl and musical prodigy who’d fled a destructive custody battle that engulfed her family in the wake of her mother’s death. She narrates her story from a safe haven she’s found with a circus troupe that’s wintering over in a quiet Florida camp where she finds solace in composing a requiem for her late mom on the troupe’s calliope.

When Suite for Calliope: A Novel of Music and the Circus, was published in the spring of 1987, it received a starred review in Kirkus, Dell bought paperback rights, and Walker sold out its hardcover first printing. The starred Kirkus happened to land on my desk on May 4, long a fateful date on my personal calendar for the opening of Undercover Books and other milestones. I phoned Ellen to give her the good news and read the review to her, learning only then that that day was her birthday. Suffice it to say, it was one of the happiest birthday calls I’ve ever made. Ellen’s run of good fortune wasn’t finished yet: Before her novel went to the printer, she learned that for her short fiction she’d won the Drue Heinz Literature Prize. This was an award associated with the literary journal Antaeus, which editor Daniel Halpern co-founded with Paul Bowles, a laurel we were able to print on the book jacket; the senior judge of the Heinz Prize that year was Nadine Gordimer. Her winning collection, In the Music Library, was also published in 1987, by Pittsburgh University Press. Quite a year for Ellen. Working with her was a great privilege and cemented my ardent interest in modern nomads and circus stories.

I’ll add that Ellen Hunnicutt’s novel played a role in cementing my relationship with my wife, artist Kyle Gallup, whom I would meet and marry in 1990-91, only a few years after the novel had come out.

Another novelist of Ellen’s period, Mark Dintenfass, praised her novel in a blurb he gave me for the jacket, commenting that the novel “teaches the reader how to read it, with its discussions of art, psychology, and philosophy being clues to its own design.” When Kyle and I met our conversations quickly took on an aesthetic and literary dimension, and I hoped she might appreciate the book as I had. I sent her a copy. When we discussed it she told me that she really liked the narrator Ada—and her friend in the story, a female painter named Kyle—and I knew for sure we could share many things.

Eyewitnesses to History

While Senior Editor and Editor-in-Chief of Kodansha America from 1992-97, I endorsed the recommendation of editorial colleague Deborah Baker who proposed we acquire trade paperback rights from Times Books/Random House to then-Illinois State Senator Barack Obama’s family memoir Dreams From My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance, which we published in 1996 as a title in the Kodansha Globe series, a nonfiction trade paperback program that paved the way for such successful series as NYRB Classics. At Kodansha I also worked with the prolific diarist and octogenarian Edward Robb Ellis, establishing an affinity in me for editing epistolary works. When his magnum opus, A Diary of the Century: Tales from America’s Greatest Diarist, was published in October 1995, though exclusive arrangements usually applied with the TV network morning shows, Ellis achieved the rare hat trick of being interviewed by Cokie Roberts on ABC, Katie Couric on NBC, and Harry Smith on CBS on their respective morning shows.

By coincidence, my next job was Executive Editor for Times Books/Random House, from 1997-2000. Newly ensconced there, I was submitted a manuscript that I knew would shock the conscience of readers, the true story of an innocent man on Virginia’s Death Row. The heart of the book was the diary of the inmate, which co-authors Joe Jackson and William Burke used skillfully in building their powerful narrative, with first-person diary entries laced through their prose. It was submitted to me during a hot summer, and when the authors chronicled the suffocatingly sultry conditions in the prison, it all but sparked a raging fever in me. With my reaction, it struck me that William Styron, a son of Virginia whose social justice advocacy included vocal opposition to capital punishment, would be outraged at the rank injustice. Through Styron’s Random House editor Robert Loomis, I got the manuscript to “Bill,” as Loomis called him, and began a dialogue with the novelist who offered to write an Introduction to the book, DEAD RUN: The Shocking Story of Dennis Stockton and Life on Death Row in America.

When I received the draft of his essay, I noted that it revealed the ultimate fate of the inmate Stockton, something I had thought we might not let slip. I called Styron, and suggested that we might refrain from doing this, to which he responded, “The specter of doom hangs over Mr. Stockton from the manuscript’s first page.” I realized he was correct, and forswore my original intention. Styron’s eloquent Introduction shone a bright light on the miscarriage of justice in the book.

As a person, I am not overly concerned about what people seem to think of me, nor do I crave lots of personal validation from others. Yet it’s an occupational hazard of the book business; as an editor and advocate for books, one is invariably focused on what people think of your titles—by publishing house colleagues, and among booksellers, sales reps, agents, foreign scouts, critics, and readers. My aspirations for my books are often sustained by blurbs, reviews, and word-of-mouth, or deflated by the lack of them. In the case of Dead Run, I was blessed by the enthusiasm of Loomis and Styron, which nourished my hopes for the book with such ardency that I was inspired to mint a quip I’m still fond of sharing about my profession: “Being an editor allows me to express my latent religiosity, since I spend so much time praying for my books.”

At Times Books, I continued working with authors of advanced age, publishing EXODUS 1947: The Ship that Launched a Nation by the trailblazing photojournalist Ruth Gruber (1911-2016), who following the Holocaust had covered the voyage of the real-life Exodus ship and became the foremost chronicler of displaced persons (DPs) in Europe during the postwar years.

As Editor-in-Chief with Carroll & Graf from 2000-2006, I edited and published THE REVENANT, an historical novel and wilderness survival tale that was the first book I acquired after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, when colleagues and I fled from our offices just blocks from the World Trade Center; though novels don’t usually carry subtitles, I suggested to author Michael Punke that he append a tag line to his book which to this day is known as A Novel of Revenge. Other books of mine during this period included national bestseller THE POLITICS OF TRUTH: Inside the Lies that Put the White House on Trial and Betrayed My Wife’s CIA Identity (2004) by Ambassador Joseph Wilson, who upon his death in 2019 was still a hero to many for his vocal opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq; THE BABY THIEF: The Untold Story of Georgia Tann, the Baby Seller Who Corrupted Adoption (2007) by Barbara Bisantz Raymond, an exposé of a nefarious baby broker, a Publishers Weekly Best Book of the Year; and the cri-de-coeur SHAKE HANDS WITH THE DEVIL: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda by Lt. Gen. Roméo Dallaire, commander of the U.N. peacekeeping force during the genocide in Rwanda. As Editorial Director of Union Square Press at Sterling Publishing, in 2008 I published COVERT: My Years Infiltrating the Mob by NBA referee Bob Delaney with Dave Scheiber, a USA TODAY Best Book of the Year, a memoir of the author’s three-year high-wire undercover stint investigating organized crime.

The above books all shared a common feature: They were written by and/or about singular witnesses to history–insiders, whistleblowers, truthtellers, muckrakers, revisionist historians–people who’d passed through a crucible of experience that left them with elevated author–ity in the eyes of the reading public, and the only person who could write the book in question, or about whom it could be written. Whether told in the first person by an author whose personal experience leaves them uniquely qualified to tell the tale, or in the third person by a reporter or scholar who has pursued a story or historical episode with single-minded passion, I remain devoted to working with authors like these, publishing imperative books that really matter in people’s lives.

I am enormously grateful for the opportunity to have worked in my family’s bookstores, and in publishing with eight different in-house jobs, and still be working in the book business, now independently for more than a decade. My experimental education turned out to be no hindrance at all, but an ideal prelude. The work has rarely been humdrum, but instead a continually stimulating, collegial, and rewarding field. While not working in the profession I had in college imagined for myself, many of the books I’ve worked on have been expressions of the search for social justice that fueled my education. I’m happy to close by noting that the familial nature of my endeavors continues with the advent in January 2020 of my adult son Ewan Turner as Executive Editor of the editorial consultancy and literary agency I now operate.

—

**Alas, the light editing that was done seems to have led to the excision of the lines just above, “I’m happy to close by noting that the familial nature of my endeavors continues with the advent in January 2020 of my adult son Ewan Turner working as Executive Editor of the editorial consultancy and literary agency I now operate.” I suppose this was because it was the last line in the whole piece and the layout was bumping up against the bottom of the page. That’s why I’m happy that I have this website, so I can run every word of the original text here, and with all the Internet links I had included in it, anticipating some day publishing the entire essay on this blog (and in the event there was a digital edition of the book). It’s also given me the opportunity to write the Introduction to it above, and offer all the context that I have above in the “The Story Behind a Handsome New Book on Books.”

-

-

Page 145

-

-

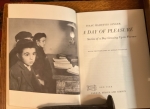

Page 146

-

-

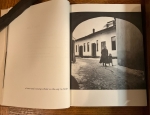

Page 147

-

-

Page 148

-

-

The hinged box and book

-

-

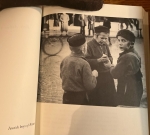

Page 465

-

-

Page 466

-

-

Page 467

-

-

Page 468

-

-

Table of Contents 1

-

-

Table of Contents 2

-

-

Among Friends quotes 1

-

-

Among Friends quotes 2

-

-

Among Friends quotes 3

-

-

Among Friends spread 1

-

-

Among Friends spread 2

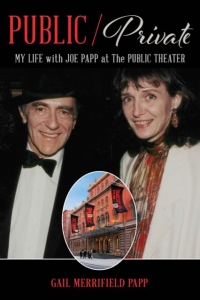

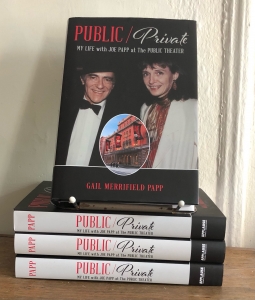

Happy publication date today to my treasured author client Gail Merrifield Papp whose PUBLIC/PRIVATE: My Life with Joe Papp at the Public Theater is out today from Applause Theater and Cinema Books, and from Audible as an audiobook narrated by actress Kathryn Grody. There was a launch event at the Public Theater last night for the book where about 150 people, including Kevin Kline, Mandy Patinkin, and Grody all feted Gail and the book. Kathryn, in particular, spoke movingly about narrating it.

Happy publication date today to my treasured author client Gail Merrifield Papp whose PUBLIC/PRIVATE: My Life with Joe Papp at the Public Theater is out today from Applause Theater and Cinema Books, and from Audible as an audiobook narrated by actress Kathryn Grody. There was a launch event at the Public Theater last night for the book where about 150 people, including Kevin Kline, Mandy Patinkin, and Grody all feted Gail and the book. Kathryn, in particular, spoke movingly about narrating it.