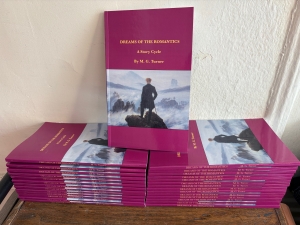

On Sale Now: “Dreams of the Romantics,” a Story Cycle about the British Romantic Poets, by M. G. Turner

As mentioned in the annual letter for Philip Turner Book Productions that we sent out a few weeks ago, Ewan will soon be publishing his first book, under his pen name M. G. Turner. Titled Dreams of the Romantics , it’s a gothic story cycle about Lord Byron, Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Dr. John William Polidori, who served as Byron’s physician.

As mentioned in the annual letter for Philip Turner Book Productions that we sent out a few weeks ago, Ewan will soon be publishing his first book, under his pen name M. G. Turner. Titled Dreams of the Romantics , it’s a gothic story cycle about Lord Byron, Mary Shelley and Percy Bysshe Shelley, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Dr. John William Polidori, who served as Byron’s physician.

The poetic circle gathered at Villa Diodati on the shore of Lake Geneva in Switzerland; it was June-July 1816, during the fateful Year Without a Summer, following the eruption of Mt Tambora near Bali which cast a pall over the earth. Mary Shelley, eighteen that year, later described “incessant rain” and “wet, ungenial” weather. Over one three-day stretch stuck indoors during inclement weather, Byron—who that same month would write his lacerating, apocalyptic poem “Darkness”—dared each of his friends to devise a gothic tale. His challenge resulted in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or Prometheus Reborn, and John Polidori’s The Vampyre, the first popular vampire story. Dreams of the Romantics will appeal to readers who have a yen for spooky stories, and an interest in or curiosity about the lives of these immortal writers.

The publisher, Riverside Press, is bringing out belles lettres titles. If you’d like to have a copy of Dreams of the Romantics, details are below.

- The 96-page trade paperback, with seven stories imagining the lives of the British Romantic poets, sells for $15 + $5 shipping (maybe more for international destinations). If you want to buy a copy, please contact us at ptbookproductions[@]gmail[.]com and we will give you electronic payment information or our address

- The painting on the front cover is “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog,” Caspar David Friedrich, 1818

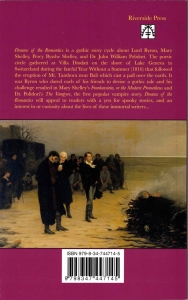

- The painting on the back cover is “The Funeral of Shelley,” Louis Edouard Fournier, 1889

- The Jenman symbol, seen on the back cover, traditionally symbolizes good fortune and wards off evil, as adopted by W. Somerset Maugham on his books.

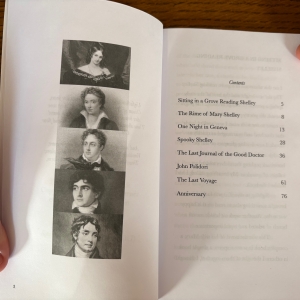

- In descending order the figures in the frontispiece shown here—opposite the titles of the stories—are Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley, George Gordon Lord Byron, Dr. John William Polidori, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.