The unfolding virus crisis, officially a pandemic since March 11, has now stretched on for more than three months, if one goes back to the first known case in the US, reported by ABC News, from Jan. 21 in Washington state. The first news report from Wuhan was even before that, the last day of 2019, Dec. 31.

There are many aspects of this situation, and the experience of living through it, that I ponder every day, beginning with the terrible suffering and sickness so many are enduring, and their families and friends, and the heroic efforts of doctors, nurses, medical techs, aides, cleaners, plus essential workers like bus drivers, cabbies, and grocery store checkers. After the grief and the solidarity I feel on a regular basis, there’s another experiential element that hits me every day in the late afternoons and early evenings. The time now being 7pm on the Upper West Side of Manhattan—where we just held our daily raucous salute to essential workers—I’m particularly mindful of it right now.

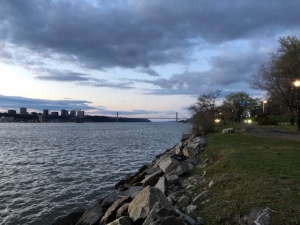

As shown above, when the crisis began building it was still late Winter. Though we didn’t have much snow this winter, it was very cold in February, in the 20s. I got a taxing dry cough then, which worried me. I thought I might’ve acquired it, or worsened it, during a cold bike ride I took one late afternoon in February, when I imbibed too much cold air, deep in to my lungs. This can happen while cycling, I’ve found, because when you’re pedaling and pumping hard, standing up on the pedals, out of the saddle going up hill, as I do in Riverside Park, I’m really breathing hard. That’s what had happened to me, I figured, though with word of the virus intensifying, I worried, too. (The cough persisted for weeks, and I later saw a nurse practitioner at my doctor’s office. We discussed if it might be Covid-19, but I didn’t have enough other symptoms so she thought not.) Then on March 6, the annual change back to Daylight Saving Time arrived, filling the second half of every day with much more daylight. Soon it became early Spring, with fruit trees in the park breaking out in blossoms, and now on April 25, it’s mid-Spring. Each day, even when it’s cloudy, runs for more hours full of daylight, stretching longer into the evening before dark finally falls.

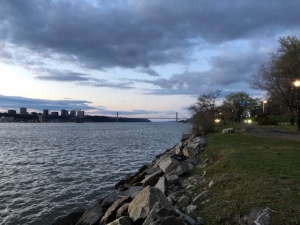

Most years I greatly appreciate the longer days of sunlight, but now with the quarantining, necessary though it is, I feel oppressed by the long days. Now, time lays heavy on my hands. This is especially true because, as alluded to above, it’s a personal routine established over many years for me—after a work day editing and doing my job as a literary agent— to be out late in the day taking rides on my bike riding along the Hudson River on the Cherry Walk in the hours approaching sunset, taking pictures with my iPhone, soaking in the last rays of the day.

And yet, the last time I was out on my bike? Early February, around the time I took in too much cold air on a ride. Of course it’s warmer now, but I don’t fancy riding with a mask on, nor do I even relish being out under the circumstances. And I would invariably jostle the mask with my helmet, and my glasses would fog, especially inconvenient as bright daylight often makes it necessary to wear my sunglasses. These past weeks I have been out for some walks down to the river, but my range doesn’t stretch nearly as far as I can ramble on my bike. And, I do want to observe Gov Cuomo’s default recommendation to stay home as much as possible.

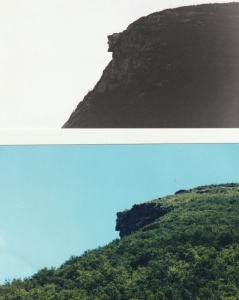

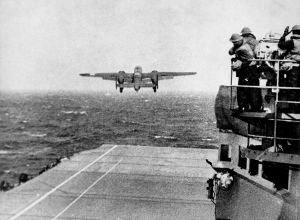

To round out this personal post, I’ll share two photos I took in late 2019, during bike rides, before the crisis, and a picture I took last week, while on a walk along the Hudson River.