Readers of this blog may recall guest contributions in creative writing earlier posted by Ewan Turner, my son. In 2012 he posted “My Father the Returner,” which won a Scholastic Writing Award and “A Game of Catch Among Friends.”

Readers of this blog may recall guest contributions in creative writing earlier posted by Ewan Turner, my son. In 2012 he posted “My Father the Returner,” which won a Scholastic Writing Award and “A Game of Catch Among Friends.”

Ewan’s new contribution is a short story narrated by a troubled physician from an earlier era.

A Horror in Body and Thought

E. Turner, M.D. • February 6th, 1887

I shall not profane my medical standing to suggest that the findings in this case have not utterly altered the fabric of my human understanding. The experience I am about to relate fills me with great disquiet, given the outcome of several manifestations that have recently come to light. By nature, I am a skeptic, accepting only reasoned rationale and employ it to detect certain self-induced psychoses. Much discussion of noteworthy events are unproven and thoroughly unbelievable, and yet there are credulous souls who give ear to these unsubstantiated claims. The border of the dream state and that of the waking is often hard to fully determine or detect so I doubt many of the stories that circulate in this age.

But I remain open minded nonetheless and in that may lie my weakness and naiveté. Most in the field of evidence-based inquiry are fortressed away from elements of order that can be called “supernatural” or “mystical.” That nomenclature is loaded with distasteful connotations and does not accurately do justice to the experiences of sensible people like myself who have seen with keen eyes the wonders, nay the horrors of the ethereal occult. The limits of my credulity have been so fantastically strained that I have soberly considered acquiring an occupation at a desk because the effects of this study have been so shattering. My composure is broken and my will remains tied to what transpired, for you see it did not take long for my serenity to wither and die. To fully articulate this transformative instance I must begin at the very moment when our subject entered my life.

His name was Mr. Malcolm Atherton, an emaciated wreck of a man, bent, gaunt and lacking in all colorful flashes of innocence. His shoulders were submerged deep below his creased neck, his posture that of a man with the load of an entire nation upon him. In all of the streets of New York never had I seen such an astounding labor of deficient breath. His eyes were rimmed with what looked like grey charcoal and his hair was a wispy collection of black strands that barely clung to his scalp. As he entered our offices he cried out for assistance in a derisive gurgle that at first shocked the nurse by the door. She grabbed his arm in a hurried motion while her partner called for my assistant and I. Noticing the commotion I rushed over to assist my colleagues and was beset by this ever more frightening sight. Atherton’s legs had given way under the extreme weight that assaulted him, collapsing him in a crumpled heap upon the floor. Drool bubbled at the corners of his mouth and a foul stench seemed to rise off his back. It was a smell so indescribably horrific that it shook the fortitudes of my person. It was the odor of some inhuman dread, the like of which I had not sensed in all my waking years. I could not even begin to articulate the premonitions of malevolence that seemed to radiate off the shrunken frame of this pathetic man.

Wasting no time we hauled him onto an examination table and hoped to pinpoint the exact cause of his astonishingly decrepit situation. My assistant sent for the police as I made desperate attempts to glean any information from the one lying before me. I asked him his name and with a choked murmur he said:

“Malcolm Atherton. Good sir, there is something evil gnawing at my heart.”

I was visibly taken aback, never had I heard uttered words like these from a patient. Many I have dealt with have not been lucid but this man seemed to be in a realm beyond lucidity and psychosis. He remained in a state between death and life, clung to by whatever malcontented plague had found him.

“What evil?” I hurriedly asked.

“It must be removed! It must be removed!” He shouted, his voice howling in torment. His eyes rolled back in their sockets and his breath mounted to a galloping pace when suddenly his body shuddered as if a light had been quenched from within. He began to convulse on the table, his body losing all semblance of control. And then as fast as it had overcome him it stopped. He became still, his breath less rapid and his heartbeat less quickened. He remained lying unconscious but visibly alive and seemingly freed momentarily of the earlier distress.

The patient remained comatose while the police arrived. To my surprise Malcolm Atherton was well known to them by reputation. I was informed that he was born on July 6th 1865 in Providence. For a time he was greatly ambitious and interested in the exploration of the unknown world. Archeology was his profession, dealing in the forgotten sarcophagi of the Egyptian pharaohs. Atherton had recently returned from an ill-fated expedition to the tomb of Sekhemkhet II or Sekhemkhet the Great, as he is called his admirers to claim the jewels said to be stored in his sepulchre. Funded by the Egyptology wing of the American Museum of Natural History, Atherton left with twenty companions and had returned with a mere eight. Nile Virus was the probable cause of these numerous deaths but the survivors suspected their comrades had been felled by forces unknown to all manner of natural law. I have since read over Atherton’s notes and concluded that articulating the precise moment of infestation would be futile and impossible. The origin of this ailment is so unknown and malignant that I cannot with clear conscience provide my own impoverished theories.

In sincerity, the truth is so foul and wicked that men of my profession would quail at its revelation, seeing it shake the foundations of all known medical inquiry. All I can in exact certainty relate is the following: On a dark North African night our patient was exploring the southern end of the Pharaoh’s tomb when he came upon a sunken statuette embedded in the center wall of the crypts’ treasure chamber. It seemed to be a carven idol whose depiction was unlike anything known to even the most erudite Egyptologists. In no way did it resemble any of the known deities of the Nile or Nubia and for a time Atherton believed he had stumbled upon a secret religion whose very existence was unknown to all form of scholarly academics. The hieroglyphic markings were utterly foreign and the image was as hideous as it was ominously foreboding. But Atherton in his foolishness ignored the obvious malevolence of the idol and secreting it in his luggage, brought it back to New York.

Atherton was in my care by an accident of fate and it was rendered necessary that I research the field of otherworldly illnesses to make a full diagnosis. I had no means or experience in dealing with dark arts or devilry so I found it profoundly peculiar to be suggesting remedies that healed men felled by influenza, dysentery and other crippling maladies. I needed to approach this convalescing person from a foreign angle but at this point none had occurred to me. I attributed my failure to the obvious factor that my expertise in demonic expulsion was entirely lacking. His disease, I feared would not cease even at death, for by this moment I admitted that something strange lurked within the confines of Atherton’s heart, working and gnawing away, leaving his carcass a castle for an infested mind. It was my duty to spare him, as it is the duty of all well-meaning physicians, but this state of discomfort had surpassed all my medical mastery. It was time to resort to a method, suspect in origin, but entirely useful to these proceedings.

Mesmerism and hypnosis were the tactics I began to wield though they at first yielded no promising affect. He seemed to be trapped in an absolute stronghold of impenetrable conflict that could be pierced by no medical means. Finally, after multiple trials I became entirely discouraged and demoralized. I have in my possession a golden watch entrusted down from the generations for quaint solidarity and I thought it wise to use the object on Atherton in the faint hope it would expedite his healing. I dangled my golden timepiece in front of his glazed eyes and cast him into a state of vulnerable oblivion and yet his reticence was astounding. My queries were all together ignored or challenged, for I knew it was not Atherton I was speaking with. No answer was forthcoming. I knew I had to fracture the curse but then a revelation dawned on me with unnatural force: I would need to conduct open dialogue with the demon’s voice itself, not the ventriloquized frame of Atherton’s body. Instead of addressing him I would need to address the infestation and coax it out of its abode.

At this time he had been in my care for two weeks with no alteration of his condition. Several doctors were brought to my side, but neither could they shed insight on the dilemma. At this juncture I was unaware that my first headway would occur at the beginning of the third week. Once more I dangled the timepiece in front of Atherton’s dulled eyes and waited. As usual I asked him the main questions:

“What is your name?”

“Malcolm Atherton”

“When were your born?”

“July 6th 1865”

“Where were you born?” At this a wind seemed to gust above his bedside and a monstrously calamitous voiced echoed from the confines of his throat.

“Outside of my mother’s womb, you bilge rat!”

I jolted back from my position by the bedside. My thoughts flooded with a sense of wonderment and also profound perturbation. I had succeeded in splintering the icy walls that surrounded my patient. Regaining my composure I continued my interrogation with a calculating mind.

“What is afflicting you, Mr. Atherton?”

“He isn’t afflicted by any abnormality, Doctor Turner, he is merely sharing his blessed heart with me. Would you care to speak to Malcolm? I can call him for you,” the demon cackled with delight. Atherton’s tongue was moved obviously by an inner conductor, one of extreme depravity.

“No I don’t want to speak with him. I would prefer to discuss this situation with you. If we are to converse, may I know your name.” I said, my designs currently unfelt by the demon.

“I am as nameless as the mountains,” he said paradoxically as Atherton’s head rose from the pillow.

“Why do you inhabit this man?”

“He trod where it was sacred, where the paths of men should be hindered from desecration.”

“What do you gain from holding him enthralled?” I was entirely wrought by a sense of disbelief.

“The inhabiting of bodies is how I will pass to the next world.” This pronouncement shattered my weakened standing. An afterlife seemed as implausible as it was unwelcome and yet here was an extraordinary moment of revelation in that matter. The following occurrence I have never articulately spoken to an intelligent soul: The strain on Atherton’s weakened heart had become such a costly hindrance that it caused the emaciated organ to halt altogether. His eyes were enameled with hinted gray and a groan of pure, ghastly termination exuded from his mouth. A gasp of pure, primordial wretchedness erupted from him and in the instant that it began his body shook with ferocious abandon. His veins flared from his arms as a slight hissing was heard escaping from all the pores of his skin. He seemed to shrink with fantastic disillusionment, his eyes widened in disbelief as the demon acknowledged his good fortune. Every crevice of Atherton’s anatomy was shrunken and scourged from within, broken down and decomposed at a speed no human could endure.

Atherton had withered to a frame so diminished that his skin barely stretched over his protuberant bones. He was a skeleton taking on the very façade of death, a death so remarkable that at that moment he looked entirely like a statue of paralyzed fear. This situation had left my medical expertise behind; I had failed in an incredible fashion. He was trapped in a state between slumber and the finality of eternal rest, caught inside the will of a diabolical plague. He remained bound to the bed in this unresolved state without any alterations in his condition. I had invariably hastened his demise without any hope of remedy. In a matter of moments all that remained of my former patient was eradicated. What was left of Atherton vibrated with alarming strain and then in the blink of my tired eyes receded into complete oblivion. His bones and tissue had dissolved into a fine white powder splayed across the hospital cot. All that remained was this bleached pumice-like dust and the remnants of the patient’s tattered garb.

The demon seemed to have transcended his shackles and achieved whatever unworldly purpose he had wished. Atherton was gone, reduced to a collection of inhuman dust and I was left cowering in the wreckage of my impoverished sanity. My days are forever marred by this affair and I doubt anyone of respectable clinical standing shall believe what I have retold in this account. I would not have accepted these claims had I been divorced from the circumstances. But they occurred, and I will testify despite every moment of disbelief from you dear reader, that they certainly occurred. Atherton is surely dead and his demonic apparition has fled to another new world.

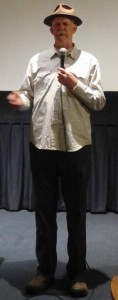

On a recent Tuesday night I went to the Tribeca Cinema for a screening of “Building Hope,” a documentary written, directed, and narrated by actor and author Turk Pipkin, who with his wife Christy also operates The Nobelity Project. The film chronicles the building of the Mahiga Hope High School in rural Kenya, which now completed, is educating more than 800 students each year. The film got an Audience Award at SXSW in 2011 and it’s easy to see why–it’s very watchable and moving, with a genuinely uplifting message, all without lapsing into saccharine simplicities. The school they designed and built with the labor of local tradespeople is also a model for sustainability, as they engineered an adjacent basketball court whose roof catches and saves rain water, providing much of what’s needed for the entire facility, in this region prone to drought. I highly recommend the film for anyone interested in education, the progress of young people in the developing world and sustainable design. It’s also a tight narrative with many memorable characters, just a fine nonfiction film.

On a recent Tuesday night I went to the Tribeca Cinema for a screening of “Building Hope,” a documentary written, directed, and narrated by actor and author Turk Pipkin, who with his wife Christy also operates The Nobelity Project. The film chronicles the building of the Mahiga Hope High School in rural Kenya, which now completed, is educating more than 800 students each year. The film got an Audience Award at SXSW in 2011 and it’s easy to see why–it’s very watchable and moving, with a genuinely uplifting message, all without lapsing into saccharine simplicities. The school they designed and built with the labor of local tradespeople is also a model for sustainability, as they engineered an adjacent basketball court whose roof catches and saves rain water, providing much of what’s needed for the entire facility, in this region prone to drought. I highly recommend the film for anyone interested in education, the progress of young people in the developing world and sustainable design. It’s also a tight narrative with many memorable characters, just a fine nonfiction film.