Update, October 28, 2024

I want to first note here that Robert Gottlieb, whom I lionized in the essay below in 2022, died about six months after I published the essay, at age 92, on June 14, 2023.

Though one is always loathe to speak ill of the dead, I also want to reflect here on the revelations about Gottlieb in Sara Franklin’s superb biography The Editor: How Publishing Legend Judith Jones Shaped Culture in America. (Atria Books, May 2024). I had referred to Jones in the 2022 essay, but knew relatively little about her until I read the recent biography. I appreciated Franklin’s perspective on how, before Judith’s decades-long career at Knopf, where she published Judith Child and a legion of other important cooks—cookbooks had been relegated to a lesser status, as somehow being merely “women’s books.” It was remarkable to read how Jones contributed to what became the elevation of food writing to a status in the culture where it properly belonged.

Alas, however, in later passages in the biography Franklin interviewed Gottlieb, Jones’s boss at Knopf. It was sobering to read passages about the relationship between Gottlieb and Jones, and read his own words acknowledging that Jones wasn’t equitably paid or fully respected at the company, even while she made monumental contributions to the company, including editing novelists John Updike and Anne Tyler for virtually all the books they published at Knopf. Gottlieb admits all this to Franklin, but seems to only faintly regret the inequity.

With all that said, I have re-read the essay, and stand by most of what I wrote almost two years ago, though am distinctly less comfortable now with what I dubbed his “likable demeanor,” as I am disappointed that he could also exhibit a waspish stinginess toward a woman who worked alongside him and contributed so much to the company and its bottom line for so many years.

I greatly enjoyed reading Robert Gottlieb’s publishing memoir Avid Reader (FSG, 2016; Picador Books, 2017), so was excited to recommend it to friends on Twitter recently as my offering under the popular #FridayReads rubric. Now, I’ll back that up with a recommendation to visitors of my blog The Great Gray Bridge.

I greatly enjoyed reading Robert Gottlieb’s publishing memoir Avid Reader (FSG, 2016; Picador Books, 2017), so was excited to recommend it to friends on Twitter recently as my offering under the popular #FridayReads rubric. Now, I’ll back that up with a recommendation to visitors of my blog The Great Gray Bridge.

With a confident but not cocky voice, the longtime editor and publisher chronicles the six-plus decades he’s been in the book trade working with authors, editing and publishing hundreds of books, dozens of them bestsellers, and many, many imperative books of our time. His long run began at Simon & Schuster in 1955, when the publisher was still run by its founders, Dick Simon and Max Schuster. Gottlieb recalls how a third leader emerged at the helm, Leon Shimkin, who had a dominating personality and took charge of many things. After Schuster died in 1957, as well as top editor Jack Goodman, Gottlieb recalls that one wag “rechristened the firm Simon and Schuster, but Shimkin.” (pg. 50)

In this era, up till the mid-60s, close-held or family-held publishing companies in America were still common.

At S&S, Gottlieb formed a troika of teamwork and powerfully productive publishing with two co-workers who would become longtime colleagues, and book business legends in their own right:

- Nina Bourne (1916-2010), advertising maven and copywriting wizard

and

- Tony Schulte (1930-2012), jack of many trades with a good head for business known widely for his likable demeanor.

S&S had a raffish character to its book list, more so than was then the case with other, longer established publishers. S&S published calorie counters, diet books, self-help (Dale Carnegie was an S&S author), puzzle books, collections of S.J. Perelman’s pun-filled essays, and other very commercial titles. In fiction, for women readers, the trio engineered a smash with Rona Jaffe’s breakthrough novel, a debut, The Best of Everything. Joseph Heller came along in 1957. Gottlieb relates how Catch-22 came to be the forever name of Heller’s hugely consequential anti-war war novel—also his debut—after its draft title was abruptly coopted by another novel coming from an established bestselling author. This story is a treat and highlights that an iconic title may look obvious only in hindsight.

The next job Gottlieb took would highlight the rise of corporate ownership.

Moving onto Knopf

In 1967, in a move that might’ve foreshadowed professional sports leagues’ high-profile trades of athletic superstars—though S&S didn’t end up with any star players in return—Gottlieb, Bourne, and Schulte announced they would be decamping as a trio to go work at Alfred A. Knopf, a more prestigious and established house. It was such a seismic event that they arranged to leave at three-week intervals, to minimize the disruptions to the old firm and to their authors with upcoming books who were staying behind. A friend of mine who worked at S&S then, Mildred Marmur—who would later become the first woman to be the chief executive of a major publishing house—recalls that even after Gottlieb left S&S he helped her. She was newly responsible for selling paperback reprint and book club rights, and he schooled her in the job of subsidiary rights director, such that some years later when she was named President and Publisher of Charles Scribner’s Sons, the NY Times reported that she was “considered the dean of subsidiary rights directors.”

Alfred A. Knopf (1892-1984) had founded his company in 1915, and it gained renown for publishing the best foreign language authors in translation, Thomas Mann, Sigrid Undset, and Andre Gide, and the Japanese masters Kawabata, Tanizaki, Mishima, and Abe, among many others. Blanche Knopf, his wife, also played a key role in the company, bringing Albert Camus onto the list. In American letters, Willa Cather was “probably the writer Alfred was proudest of having captured” (pg 106) for their list. In later years Knopf editor Judith Jones began working with John Updike, who continued with the house his entire career. To show the editorial talent, consider that Jones’s reach and ambit took in Julia Child, who only ever published with Knopf. The instantly indentifiable Borzoi colophon also could be found on the spines of the crime novels by the first generation of hardboiled detective writers, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and James M. Cain, and then those writers’ notable heir, Ross MacDonald, creator of the Lew Archer novels.

The Knopfs’ son Pat* (officially “Alfred, Jr.”) worked at the family firm for a time, but the bullying ways of the elder Knopf had soured the younger man on taking over the firm someday. In the mid-60s, Alfred chose his succession plan: he sold the company to Random House, which itself had earlier been bought by RCA.**

Though no longer running Alfred A. Knopf, Alfred and Blanche still worked there, while Gottlieb, Bourne, and Schulte began livening up the place. Their infusion of new ideas sometimes clashed with Alfred’s former ways. Gottlieb tells a scalding tale of how Nina Bourne became the target of a “furious memo” from Alfred. This occurred after a book ad ran in the NY Times that in its design played with the sacrosanct Borzoi logo. Amid the tempest, Gottlieb was “itching to storm into Alfred’s office to tell him to fuck off. No, Nina said; she wanted to deal with him in her own way.” The details of how she did so are delicious.

Gottlieb added much high profile nonfiction to the list, including in 1974 most famously The Power Broker by Robert Caro, who later undertook his multi-volume enterprise chronicling the life and career of LBJ with Gottlieb editing. Memoirs came from Gloria Vanderbilt (Once Upon a Time), Lauren Bacall (By Myself) and Liv Ullman (Changing). His accounts of working with these authors is consistently entertaining. With Bacall, he reports, “We had only one difficult moment. There was a gorgeous picture of her on the front cover, and on the back I showed her with Bogart. Absolutely not, she exploded; this was her book, not his. That really pushed my buttons. ‘Listen…’ I said, ‘people want to know about you and him, and you’ve written hundreds of pages about him. It’s my job to sell your book.’… ‘Fine,’ she said.” (pg. 105)

Noting the show business books and fizzy celebrity titles, it must also be said that Gottlieb showed wide range and consistently good taste with books that ran from the commercial to the literary; consider that not only did he edit a number of Michael Crichton’s science-y medical thrillers, like his debut The Andromeda Strain, he also worked with Doris Lessing on several of her major novels, and many of Toni Morrison’s books.

During this period, the house also hired and retained many stellar editors who over decades acquired great books for the house of Knopf, such as Ashbel Green and Victoria Wilson, to name only two. In other departments, they hired people who would go on to be major contributors in the overall growth of the book business in the twentieth century, and now twenty-first, like Jane Friedman. As head of what was then known as the Promotion department, she minted—with Julia Child as the author—the first city-to-city author tour to promote a new book. The book tour for Mastering the Art of French Cooking visited many major cities, supported by local morning show TV spots and well-attended signings in the book departments of major department stores, where the inimitable Julia would do a cooking demonstration. Friedman later started Random House Audio, the first audio division at a major book publisher.

A Bookseller’s Perspective

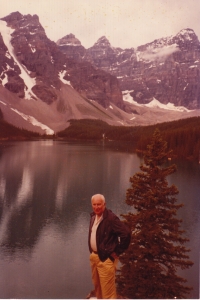

I was a retail bookseller during much of this time, with Undercover Books in Cleveland, the indie bookstore chain I started in 1978 with my two siblings and our parents, and I can attest to the appeal and sheer salability of Knopf titles, and books from the whole Random House domain at the time. During a visit to New York City in the 1980s, my brother Joel (1951-2009) and I paid a call at the Random House building in Manhattan, where the director of sales Dennis Hadley welcomed us. He was grateful to our stores for having helped the company make Martin Cruz-Smith’s thriller Gorky Park (Random House, 1983) into a bestseller. (Knopf and Random House were sold by the same sales reps.) We’d received a galley of the Cold War suspenser from our rep, and loved it, and were excitedly talking it up to our customers prior to the arrival of finished books. Hadley knew about this and, through the publisher’s adroit sales and publicity channels, word got to Edwin McDowell, publishing reporter at the NY Times, that he could contact our store for a bookseller’s take on why we were so confident we would do very well with the book, having already placed a seventy-five copy opening order for the upcoming hardcover. When McDowell phoned I answered and was quoted in his “Behind the Bestsellers” column about how engrossed we had all been by the book, passing around what became an increasingly bedraggled galley among all five of us. I related to McDowell that at one point, the contents of a bottle of shampoo had been spilled on the galley, but we dried it out and continued passing it on to the next one of us in line, a colorful detail he included in his story.

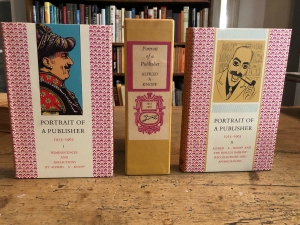

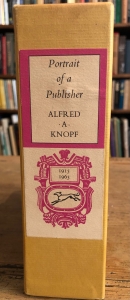

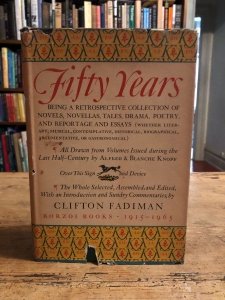

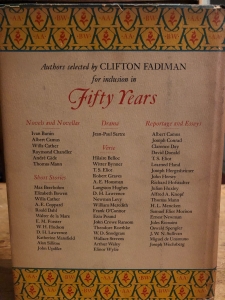

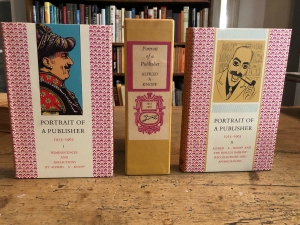

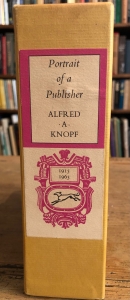

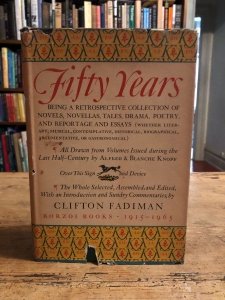

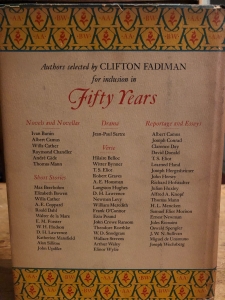

At one point during the conversation in Hadley’s office, he stood up, briefly excusing himself. Upon returning he announced he wanted to give us each a gift. In his hands he held the celebratory two-volume slipcased set pictured below. Surely, one set would have been dayenu (enough), for the two of us, but instead we each left with one, deeply grateful for the gesture. The commemorative set was privately published for “friends of Alfred A. Knopf” in 1965, the company’s 50th anniversary year. Knopf’s stylish Borzoi colophon, and the stunning design and typography of their books were marks of excellence, so evident in the package shown here in photos. That milestone year also led to a special volume edited by Clifton Fadiman—this one was offered for sale to the reading public—and which I later added to my library (pictured at the bottom of this post).

At one point during the conversation in Hadley’s office, he stood up, briefly excusing himself. Upon returning he announced he wanted to give us each a gift. In his hands he held the celebratory two-volume slipcased set pictured below. Surely, one set would have been dayenu (enough), for the two of us, but instead we each left with one, deeply grateful for the gesture. The commemorative set was privately published for “friends of Alfred A. Knopf” in 1965, the company’s 50th anniversary year. Knopf’s stylish Borzoi colophon, and the stunning design and typography of their books were marks of excellence, so evident in the package shown here in photos. That milestone year also led to a special volume edited by Clifton Fadiman—this one was offered for sale to the reading public—and which I later added to my library (pictured at the bottom of this post).

After more than twenty years at Knopf, Gottlieb writes that “the amusement was draining out of things. I was doing more and more, and our profits were consistent, but the personal cost was mounting. When a book hit the bestseller list, when an important author joined us, when a major award was won, it had always been a moment for celebration. Now it was just a relief—okay, this worked, so onto the next. It wasn’t being jaded, it was exhaustion.”

With that, Gottlieb became editor of The New Yorker in 1987, a job he held for about five years.

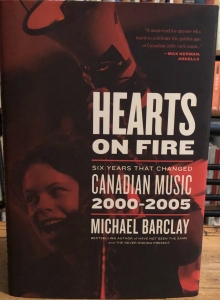

Significantly for Gottlieb, it was also around this time that he began publishing written work of his own, with a number of books focused on dance, jazz, the American songbook, literary classics, and this memoir. In Avid Reader it’s exciting to see him recount taking these steps in his own writing. I too hope and expect to begin publishing written work of my own in book form at some point. Meantime, I publish essays like this one, as well one about a professional encounter I had with William Styron, and essays about bi-nationalism on my other website Honourary Canadian.

Gottlieb writes that he is sometimes asked to address college students who are considering a career in publishing or journalism. His advice is pragmatic and sensible. To illustrate his central idea that publishing is a service business, and that editors work for the book and the author, he relates a memory from his years at S&S:

“My love affair with readers was ignited…by the message that Richard L Simon expressed to the entire staff [with] bronze paperweights on which were etched these words:

GIVE THE READER A BREAK (pg. 318)

That succinct philosophy can be adhered to in many ways. For me: Keep the price of a book as low as possible. Make sure the type is legible—when possible, generous; readability is all. Don’t talk about an important photograph or portrait and then not show it. Deploy useful running heads—the name of a particular story or essay rather than the name of the author….Don’t over-design.”

Now in his nineties, Gottlieb and his longtime author Robert Caro are the subjects of a new documentary by Lizzie Gottlieb, daughter of Robert Gottlieb and his wife, actress Maria Tucci. The film is titled Turn Every Page—The Adventures of Robert Caro and Robert Gottlieb. I’m excited I’ll have a chance to see the editor and author at the NY Public Library on December 12. More info on tickets for that event here, which will be viewable in-person and virtually.

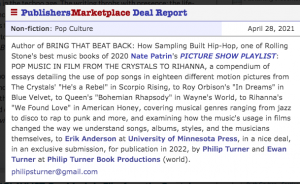

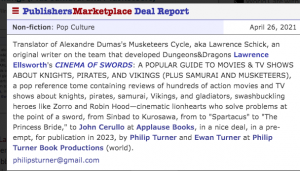

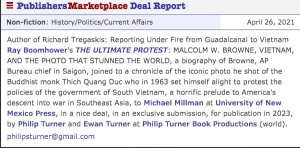

As an editor for almost thirty-seven years myself, I am always excited when I have an opportunity to work on books that I know readers will find engrossing, and which I believe they will be apt to read avidly. Among the books I’ve edited that display this quality are The Revenant: A Novel of Revenge by Michael Punke, the historical novel about the American frontiersman Hugh Glass, and The Last Battle: The Mayaguez Incident and the End of the Vietnam War by Ralph Wetterhahn, on the hijacking of an American merchant vessel in Southeast Asia during the waning days of the Vietnam War. In fact, it strikes me that the attribute of avidity is the most valuable coin of the realm in book publishing. I would devise a formula to mint more of it if I could. At the time of Gottlieb’s move to Knopf in 1967, one newspaper headline trumpeted “Avid Reader to Head Knopf.” Robert Gottlieb’s own writing in this book displays that quality in abundance, making the title he chose for his memoir—such a pleasure to read—supremely apt.

Lest I seem to be idealizing Gottlieb unduly, I’ll add that just like anyone who’s worked in publishing alongside other people, with ambitious people striving to do good and important work, I don’t doubt that he didn’t get along with everybody, nor all with him. Few people in any field get along with everyone. In a discussion of the fact that authors sometimes moved on from Knopf (pg 176), and that he was sometimes the beneficiary of a writer leaving another house, Gottlieb writes that he “disliked” Don Delillo’s “agent, and no doubt she reciprocated.” But he doesn’t name the agent, perhaps not wanting to needlessly stir up old acrimony, though people in the book business will readily know who Delillo’s agent of longstanding was. Though not a saint, Robert Gottlieb comes off as genuinely likable, certainly to me.

If I have the opportunity to meet Gottlieb someday, I’ll be eager to tell him that back in the day I worked for the US outpost of Kodansha, the large Japanese publisher, around the time he was a judge for a translation prize they sponsored. We share an affinity for modern Japanese cultural arts. I would also tell him that in my bookselling career I personally sold many of the books that he edited and published, including the bestsellers mentioned above, and others, such as David O. Selznick’s Hollywood by Ron Haver. I would add that in 2006 I edited and published a notable memoir by the under-appreciated writer, and one-time Hollywood talent agent, Clancy Sigal (1926-2017), which included much about his life with Doris Lessing in London in the 1960s, and the couple’s engagement with a social and literary circle that included the gadfly psychiatrist R.D. Laing.

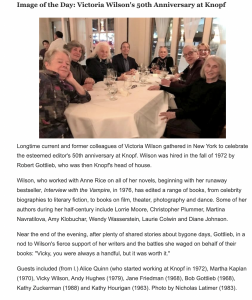

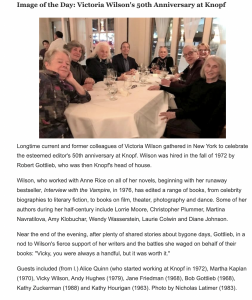

Gottlieb describes an annual celebration that longtime Knopf co-workers still enjoy, and the day I was reading that passage in Avid Reader, I came upon this item in the book industry newsletter Shelf Awareness, marking the 50th anniversary at the company of the aforementioned editor Victoria Wilson, shown here in the photo are former and current Knopf colleagues, Alice Quinn (started at the company in 1972), Martha Kaplan (1970), Wilson (1972), Andy Hughes (1979), Jane Friedman (1968), Kathy Zuckerman (1988), and Kathy Hourigan (1963). The photo is credited to Nicholas Latimer, another erstwhile Knopf colleague (1983).

A penultimate note on reading Avid Reader, and writing about it: The nearly two dozen authors and books I’ve mentioned in this essay, books that Gottlieb was responsible for editing and publishing, are only a bare fraction of the dozens of books about which he tells stories in his enjoyable memoir. In fact, the book’s index is devoted only to names of people who come up in the book, but I noticed, not to book titles—doing so would have probably made the index much longer for FSG to print!

Reading this book stirred up a lot of good memories. The experience of it was like eating a big sundae, a totally enjoyable treat.

—

Endnotes

*In 1959 Pat Knopf (1918-2009) was among the founders of Atheneum Publishers. Atheneum later merged with Scribner, and that combined entity was acquired by Macmillan in 1984. My second editorial job was with Collier Macmillan from 1986-89, and Pat still worked there then. My office was next door to his, and I found him a friendly work neighbor. Though I’m glad to have had that brush with a figure connected to so much distinguished publishing history, I regret I never engaged him in a full conversation about the business and his time in it. At the time, I was unaware of most of the backstory involving him and his parents’ company. Some of that backstory can be gleaned from this NY Times obit of the younger Knopf.

**The Radio Corporation of America, RCA’s full name, was the first major corporation I know of to own a US book publisher, when that new owner had no prior interest, financial or intellectual, in books.

***A note on terminology: I use “publisher,” “publishing company,” and I’m partial to the expression, “publishing house.” In fact, publishing companies have long been known as ‘houses’ because they (are supposed to) offer hospitality to writers.

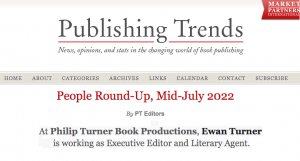

It’s fun and rewarding to have such a knowledgeable colleague and partner whose instincts and judgment I trust completely. When the year began he was our Managing Editor, and then mid-year I promoted him to Executive Editor and Literary Agent, which was announced in the Publishing Trends newsletter in July. The dual role is emblematic of our makeup as a joint editorial services consultancy and literary agency. He’s heading our New Stories division, devoted to cultivating new work in fiction, narrative nonfiction, and memoir.

It’s fun and rewarding to have such a knowledgeable colleague and partner whose instincts and judgment I trust completely. When the year began he was our Managing Editor, and then mid-year I promoted him to Executive Editor and Literary Agent, which was announced in the Publishing Trends newsletter in July. The dual role is emblematic of our makeup as a joint editorial services consultancy and literary agency. He’s heading our New Stories division, devoted to cultivating new work in fiction, narrative nonfiction, and memoir.

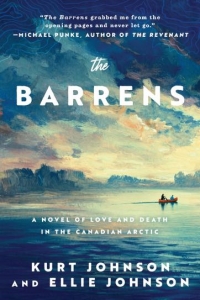

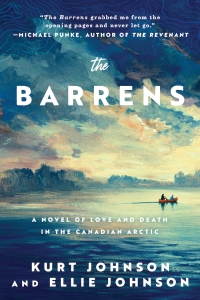

THE BARRENS: A Novel of Love & Death in the Canadian Arctic by Kurt Johnson and Ellie Johnson (Arcade Publishing, May 2022), sold under our New Stories rubric. Chosen by the Women’s National Book Association for their annual Great Group Reads program, attesting to its suitability as a novel for book clubs. “Two young college women embark on a canoe trip down the Thelon River in Canada’s Barren Lands when a tragic accident turns a wilderness adventure into a battle for survival in this debut novel…A poignant and engaging thriller with a formidable lead character.”—Kirkus

THE BARRENS: A Novel of Love & Death in the Canadian Arctic by Kurt Johnson and Ellie Johnson (Arcade Publishing, May 2022), sold under our New Stories rubric. Chosen by the Women’s National Book Association for their annual Great Group Reads program, attesting to its suitability as a novel for book clubs. “Two young college women embark on a canoe trip down the Thelon River in Canada’s Barren Lands when a tragic accident turns a wilderness adventure into a battle for survival in this debut novel…A poignant and engaging thriller with a formidable lead character.”—Kirkus ROOSEVELT SWEEPS NATION: FDR’s 1936 Landslide and the Triumph of the Liberal Ideal by David Pietrusza (Diversion Books, August 2022; Blackstone Audio). “Historian Pietrusza creates a brisk, spirited narrative, abundantly populated and bursting with anecdotes, revealing the president’s trials and turmoil as he faced reelection….Prodigiously researched and exuberantly told.”—Kirkus, starred review

ROOSEVELT SWEEPS NATION: FDR’s 1936 Landslide and the Triumph of the Liberal Ideal by David Pietrusza (Diversion Books, August 2022; Blackstone Audio). “Historian Pietrusza creates a brisk, spirited narrative, abundantly populated and bursting with anecdotes, revealing the president’s trials and turmoil as he faced reelection….Prodigiously researched and exuberantly told.”—Kirkus, starred review HEROES ARE HUMAN: Lessons in Resiliency, Courage and Wisdom from the COVID Front Lines by Bob Delaney with Dave Scheiber (City Point Press, September 2022; audiobook, Tantor Media). “Offers insights into life on the front lines during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic…An eye-opening work about health care workers’ sacrifices and burdens.”—Kirkus

HEROES ARE HUMAN: Lessons in Resiliency, Courage and Wisdom from the COVID Front Lines by Bob Delaney with Dave Scheiber (City Point Press, September 2022; audiobook, Tantor Media). “Offers insights into life on the front lines during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic…An eye-opening work about health care workers’ sacrifices and burdens.”—Kirkus LURKING UNDER THE SURFACE: Horror, Religion, and the Questions that Haunt Us by Brandon Grafius (Broadleaf Books, October 2022; audiobook, Tantor Media). “Grafius teaches us how to welcome horror as a constant companion in a world plagued by real evil.”—Sojourners

LURKING UNDER THE SURFACE: Horror, Religion, and the Questions that Haunt Us by Brandon Grafius (Broadleaf Books, October 2022; audiobook, Tantor Media). “Grafius teaches us how to welcome horror as a constant companion in a world plagued by real evil.”—Sojourners LAST CIRCLE OF LOVE, a novel by Lorna Landvik (Lake Union, Amazon Publishing, December 2022; audiobook narrated by the author, Brilliance). “This warm and funny book is vintage Landvik, with an ensemble cast of salt-of-the-earth women with names like Marlys and Charlene who tiptoe into the world of lust and examine what, as they say, turns them on. None of it is really erotica, of course, but more practical things like gallantry, compliments, understanding and forgiveness.”—Laurie Hertzel, Minneapolis Star-Tribune

LAST CIRCLE OF LOVE, a novel by Lorna Landvik (Lake Union, Amazon Publishing, December 2022; audiobook narrated by the author, Brilliance). “This warm and funny book is vintage Landvik, with an ensemble cast of salt-of-the-earth women with names like Marlys and Charlene who tiptoe into the world of lust and examine what, as they say, turns them on. None of it is really erotica, of course, but more practical things like gallantry, compliments, understanding and forgiveness.”—Laurie Hertzel, Minneapolis Star-Tribune