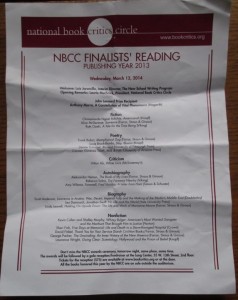

Night II of the NBCCs–Book Prizes Awarded

Monday March 17 update, video of the NBCC Awards ceremony:

—–

The concluding evening of the National Book Critics Circle annual awards last night at the New School auditorium was a jubilant celebration of the book with generous recognitions given to critics and authors alike. Having enjoyed the author readings on Wednesday night I was eager to hear who the winners would be. The program began with remarks by NBCC president Laurie Muchnick, reminding the audience that members of the organization spend months each year reading and keenly debating the merits of all the books in the six categories. With the housekeeping taken care of, the procession of awards began.

The concluding evening of the National Book Critics Circle annual awards last night at the New School auditorium was a jubilant celebration of the book with generous recognitions given to critics and authors alike. Having enjoyed the author readings on Wednesday night I was eager to hear who the winners would be. The program began with remarks by NBCC president Laurie Muchnick, reminding the audience that members of the organization spend months each year reading and keenly debating the merits of all the books in the six categories. With the housekeeping taken care of, the procession of awards began.

First up it was time for a new award, the John Leonard Prize, named in memory of the longtime NBCC member and ebullient NY Times reviewer. Each year it will be given to an author for a first book, in any genre. It had earlier been announced that Anthony Marra, author of A Constellation of Vital Phenomena (Hogarth Press at Crown Publishing) was the inaugural recipient. His novel is set amid the war in Chechnya. Then, Katherine A. Powers, who has a regular books column in the BN Review, received the NBCC’s Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing. She gave a congenial talk setting forth her own principles of reviewing. Among these was that she tries to avoid lordly pronouncements of approval or condemnation, as if she were representing some “cohort of worthies.” She declared herself in service to the reader and the author, and quoted a memorable line from H.L. Mencken: “Criticism is prejudice made plausible.” Next, pioneering man of Hispanic letters Rolando Hinojosa-Smith received the Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award for his contributions to the literature of Mexican-Americans.

After naming all five poet finalists, chair of the Poetry committee David Biespiel began the presentation of awards that, unlike the three above, were not decided until yesterday afternoon, only a few hours before this ceremony. After naming all the poet finalists while their four book jackets flashed across the on-stage screen, David announced that Frank Bidart was the recipient of the NBCC for his book Metaphysical Dog (FSG). Bidart brought some papers to the lectern, and joked that each time he’s nominated for something, he prepares remarks and when he doesn’t win, files them away, continually adding to them each time he’s on a shortlist. This got a laugh from the audience, especially, after he said, “It’s true.” In fact, his acceptance speech was an elegant one. He described himself as a neo-modernist, not a post-modernist, saying he didn’t feel the need to be in conflict with his poetic predecessors. As to his own work, citing the words of a critic who upon hearing Maria Callas for the first time had written that the experience was like “biting in to a lemon,” he offered a hope that his own poems offer readers a similarly astringent quality. Quoting a great sentence from King Lear, “Ripeness is all. Come on.” Bidart pointed out that profound as it is, it’s not actually the last line of the scene. Instead, Gloucester points playgoers to the plurality of existence, uttering, “That’s true, too.”

Next, the award in Criticism was given to Franco Moretti for his book Distant Reading (Verso Press), with essays that use data, charts and other apparatus to consider reading in new ways. With Moretti’s arrival at the lectern he made a confession that held true the rest of the night: he had not expected to win and didn’t prepare remarks. He had a lovely Italian accent and the audience found him charming.

With a new precedent oddly established by Moretti, each of of the four recipients who followed uttered a version of the same thing, accepting the award graciously, and briefly. As it happened, four times in a row, the audience laughed a little more at it, as the recipient would sheepishly cop to his or her forgivably mild dereliction. Mild because audiences always expect to be held for a long time, and this was a veritable vacation from standard awards palaver.

Autobiography committee chair Eric Banks announced Amy Wilentz and her book on Haiti, Farewell, Fred Voodoo (Simon & Schuster), as the recipient of the NBCC. Once behind the lectern Wilentz explained that she’d written earlier books on Haiti–a country she called her “muse”–and this one was the most autobiographical of them, but she implied that because it wasn’t a proper autobiography she had really expected a different winner to be called up to the stage. And her category was very strong, filled with great writers of first-person narrative, a favored genre of mine. Next up, Leo Damrosch, winner in Biography for Jonathan Swift: His Life and His World (Yale University Press), said that he’d always written for academics and so doubted his book would be selected. He was off before I could take a picture, so the one with this post is the one I took the night before, at the readings. Sheri Fink, whose Five Days at Memorial: Life and Death in a Storm-Ravaged Hospital (Crown Publishing) I first heard about when her editor Vanessa Mobley presented it at last year’s BEA Buzz panel. Fink seemed truly taken aback at this recognition given to her book. For the last award, in fiction, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie of Nigeria allowed as how she had been so tickled to be on the same shortlist as her former professor, Alice McDermott, she just hadn’t thought her novel Americanah would win. As she walked to the stage, she shouted in jubilation, a celebration the audience audibly shared with her.

With that the ceremony–in a tidy 90 minutes–was over. Most of the audience repaired to another New School building one block away for the gala reception. A hungry and thirsty crowd met there and partied for a much greater stretch of time than the ceremony’s duration. During the party I met and spoke with many of the finalists: critic Katherine A. Powers; poet Denise Duhamel; essayist Franco Moretti; Marianne Moore biographer Linda Leavell; Whitey Bulger chroniclers Kevin Cullen and Shelley Murphy, and their editor at W.W. Norton, Tom Mayer; observer of New Orleans’ tragic triage, Sheri Fink; novelist Ruth Ozeki; and one of my favorite writers at The New Yorker, Lawrence Wright, whose reading from Going Clear I had found so chilling the night before. I also enjoyed talking with NBCCers Walton Mayumba, Karen Long, Anne Trubek, Tom Beer, Eric Liebetrau and his writer wife, Signe; Ron Charles; and Marcela Valdes. Also enjoyed meeting for the first time one of my favorite tech writers, Andrew Leonard, there celebrating the memory of his father John Leonard; book agent, Andrew Blauner; editor Philip Marino of Liveright; journalist Casey Schwartz, Riverhead Books publicist Katie Freeman; and indie publicist Michelle Blankenship. Below are my pictures from last night. If you enjoyed this post, don’t miss its counterpart on the readings.