“J.M.W. Turner: The Majesty of Vision” by Kyle Gallup

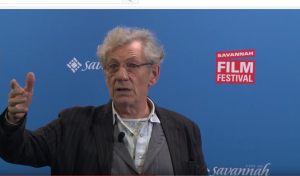

/1 Comment/in Art, Film, TV, Photography, Fine Printing & Design, Personal History, Family, Friends, Education, Travels /by Kyle Gallup“J.M.W. Turner: Watercolors from Tate at the Mystic Seaport Museum”

Painting as an Aide-Memoire

Stormy seas as atmospheric notations; sheer, floating sunsets; a bright-white moonrise over a glassy body of water; imaginary, architectural views of early nineteenth-century buildings; and a pastoral River Thames on a cloudy summer day. These paintings comprise five of the ninety-two watercolors, four oil paintings, and one of Joseph Mallord William Turner’s last sketchbooks that are on view in a current exhibition, “J.M.W. Turner: Watercolors from Tate,” at the Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, Connecticut, through February 23, 2020.

The watercolors are thoughtfully selected from the Turner Bequest, which contains 30,000 works on paper left to Great Britain and housed by the Tate since 1856, five years after the artist’s death. The show is curated by Dr. David Blayney Brown,Tate’s Manton Senior Curator of Nineteenth Century British Art, and organized chronologically with informative title cards that provide important context for these visionary works within the larger arc of Turner’s long public career.

As you enter the gallery, the first dark, silvery watercolors were done when Turner (1775-1851) was in his early twenties and one, “View in the Avon Gorge,” was painted when Turner was only a precocious sixteen-year-old. In it we see a gorge and river view with an overhanging tree, rock cliffs in powdery blues, and silvery-green leafed trees, delicately painted and already masterfully detailed. These early works, along with the thousands of others on paper, filled his residence after his death. The majority of the bequest was part of Turner’s private collection, made for himself, and not intended for public viewing.

Watercolors—a fragile, fugitive medium—are seldom displayed in public. They are loaned, transported, and exhibited even less often, so it’s very special to have the works on display in the United States at all, and an opportunity to see Turner in an intimate light, not as Royal Academician and renowned artist of dramatic oil paintings, but as a far-seeing, romantic, and hard working painter.

The exhibition has many watercolors with atmospheric notes; dashes and washes of buoyant color; sight and thought as one. I can imagine that Turner used these simple landscapes for reference, and as aide-mémoire when painting other works.

“A Wreck Possibly Related to ‘Longships Lighthouse, Land’s End’ (1834),” “Sunset Across from the Terrace of Petworth House (1827),” and “Coastal Terrain (1830-45),” give the viewer a sense of the weather conditions, movement, and hour of the day. They are Turner’s visual shorthand—pared down, yet still encompassing a larger sense of what Turner was looking at and thinking about at particular moments in time.

For the full essay with all illustrations, please click here.

“A Wreck, Possibly Related to ‘Longships Lighthouse, Land’s End (1834)”. Turner Bequest 1856 © Tate 2019

Bonnard at the Tate in London

/0 Comments/in Art, Film, TV, Photography, Fine Printing & Design, Personal History, Family, Friends, Education, Travels /by Philip TurnerAn Ode to Michael Powell’s 1936 Film “The Edge of the World”

/0 Comments/in Art, Film, TV, Photography, Fine Printing & Design /by Philip Turner

I was cheered to see in this recent NY Times magazine travel piece that Powell and his work also enchant Indian-born novelist Neel Mukherjee, who for his story visited the mostly depopulated St Kilda archipelago where “The Edge of the World” was filmed. I shared Mukherjee’s story and linked to it on Facebook, and embedding that post here with the NYT link.

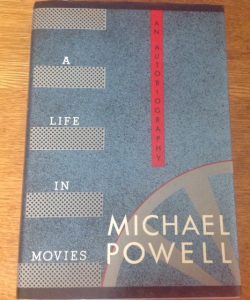

The epigraph in Powell’s 1986 autobiography, attributed to Hein Heckroth, art director on “The Red Shoes,” is

Movies are the folklore of the twentieth century

“All my life I have loved running water. One of my passions is to follow a river downstream through pools and rapids, lakes, twists and turnings, until it reaches the sea. Today that sea lies before me, in plain view, and it is time to make a start on the story of my life, to remount it to its source, before I swim out, leaving behind the land I love so much, into the grey limitless ocean.”

Powell tells great stories about the making of his movies, including the duo filmed in the Hebrides.

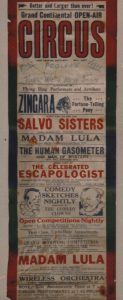

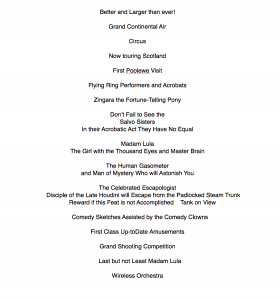

From the Human Gasometer to Madam Lula on a Favorite Circus Poster

/0 Comments/in Art, Film, TV, Photography, Fine Printing & Design, Personal History, Family, Friends, Education, Travels /by Philip Turner Some years ago during a visit to Scotland, I visited the West Highland town of Gairloch, and its excellent Heritage Museum, where I saw this great old circus poster on display, promoting a circus that was some years earlier performing in the nearby town of Poolewe. Recently, I came upon my photographic print of the poster and scanned it to publish on this blog, where in years past I’ve published other posts on circus topics, like this one titled “Life is a Carnival.”

Some years ago during a visit to Scotland, I visited the West Highland town of Gairloch, and its excellent Heritage Museum, where I saw this great old circus poster on display, promoting a circus that was some years earlier performing in the nearby town of Poolewe. Recently, I came upon my photographic print of the poster and scanned it to publish on this blog, where in years past I’ve published other posts on circus topics, like this one titled “Life is a Carnival.”

I love the way posters like this vary the size, spacing, color, and fonts to bill each act and performer in distinctive way. I’ve typed it out so readers of this post could easily read the colorful copy the promoter wrote back in the day. There was no year on the poster, so I’m left to imagine that the circus might have active sometime in the first third of the twentieth century.

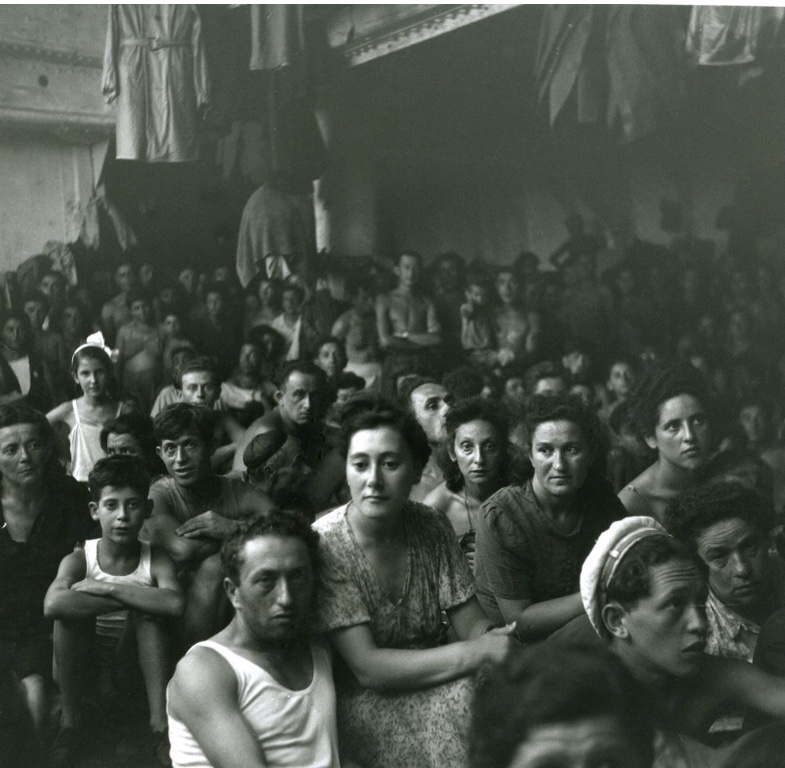

For my friend Ruth Gruber, Sept 30, 1911-Nov 17, 2016

/2 Comments/in Art, Film, TV, Photography, Fine Printing & Design, Personal History, Family, Friends, Education, Travels, Philip Turner Book Productions /by Philip TurnerThe funeral for my dear friend and longtime author Ruth Gruber will be this morning, Nov 20, 11am at B’nai Jeshurun on W 88th St in Manhattan. She died on Thursday at age 105. One of her mentors was Edward Steichen, who urged her, “Take pictures with your heart,” which she always did. Here’s an album with two pictures of her, and a few of her images. Among her hundreds of great photographs, these three are some of her most moving. Links below offer more info on Ruth’s long life and career.

All my blog posts on Ruth Gruber

Appreciative for a Shoutout to My Editing of “The Revenant” from Canadian Pal Grant Lawrence

/0 Comments/in Art, Film, TV, Photography, Fine Printing & Design, Books & Writing, Philip Turner's Books & Writing /by Philip TurnerI'm tickled that Canadian music journalist, CBC broadcaster, author, friend—and devoted reader of adventure tales—Grant… Posted by Philip Turner on Wednesday, 23 March 2016

Righteous Words from Shakespeare, So Pertinent to Today’s Refugee Crisis—Read by Sir Ian McKellen

/0 Comments/in Art, Film, TV, Photography, Fine Printing & Design, News, Politics, History & Media /by Philip Turner![]()

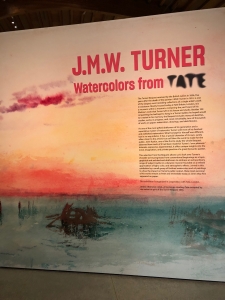

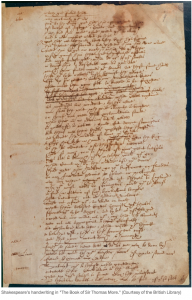

In what appears to have been November 2010, at the Savannah Film Festival, Sir Ian McKellen had occasion to read lines of Shakespeare from a play called “The Book of Sir Thomas More,” words set in the voice of More, a councillor to King Henry VIII. Shakespeare didn’t write the original, but contributed to rewriting portions of the drama with other contributors some 400 years ago. It is not a well-known work, and McKellen says here that it may have never been performed for an audience until 1964. This 5-minute youtube clip is linchpin of a good Washington Post article published today by reporter Karla Adam, the headline for which opens this post, pretty well summing up the message of the words read by Sir Ian.

Adam also reports that the text of the passage, in Shakespeare’s own handwriting, has recently been digitized by the British Museum, and is featured in a new exhibit at the Folger Library in Washington, DC. McKellen explains that earlier, a year before his appearance at the Savannah Film Festival, in London at Trafalgar Square, or St Martin-in-the-Fields, as it would’ve been known in Shakespeare’s time, a man and his gay partner were set up on three hooligans, who killed him. The location is also where in the play More gives this speech. Below is a still from the very powerful video, and click here for the video itself. You may want to first read the Washington Post article for full context as I had done before I watched it.

I’ll add a New York City note to this post, about “a celebrity sighting.” Though they don’t occur all that often here, that’s what I dub them. On two occasions my wife and son and I have had occasion to meet and speak with Sir Ian McKellen. He is approachable, down-to-earth, and charming. The first time was in 2003, soon after “The Fellowship of the Ring,” the first of Peter Jackson’s Tolkien movies, had premiered. The three of us had just seen the movie a few days before, and we bumped in to him at the old Weber’s Odd-Lot discount store near W 72nd St and Broadway. He was in town doing a Strindberg play on Broadway with Dame Helen Mirren. With my son Ewan, then about seven years old, we found ourselves behind him in line, while my wife was elsewhere in the store for a moment. The wait in line was long enough for me to spot him, nudge my son, and whisper who was in front of us. I leaned in a bit toward the gentleman and without invading his space, said something like, “Sir Ian, congratulations on all the great roles you have this season.” Turning toward us with a warm smile we began conversing. I mentioned we’d only a couple days earlier seen the movie and had found it breathtaking. I added, “We miss Gandalf,” thinking of the fall in to the abyss he’d suffered fighting the Balrog. Sir Ian adopted the deep voice of the Grey Wizard, and addressing Ewan especially, he intoned reassuringly, “He’ll be changed, but he’ll be back. He’ll be changed, but he’ll be back.”

The other time was a few years later, at BAM where the three of us had just seen him perform as King Lear. We waited afterward at the stage door and came out to greet the handful of fans clustered there. He spoke to each group for a few minutes, for a warm and friendly chat. He is a good and decent man, and his humanity shines through in this remarkably fluent rendering of Shakespeare words about refugees, or “strangers” as they’re called here.