Finalists’ Readings at Last Night’s NBCCs

Monday March 17 update, video of the NBCC Readings night:

—–

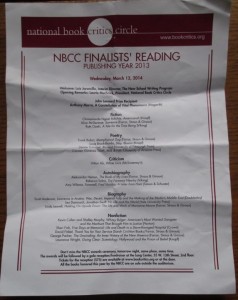

As I try to do every March when the calendar comes round to the annual awards week of the National Book Critics Circle, I attended last night’s program of readings given by many of the nominated finalists. To the left is the evening’s program. Highlights were numerous, including Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s humorous narrator’s observations about blogging, of all things, from her novel, Americanah; Alice McDermott, with a carefully paced reading from Someone; Ruth Ozeki’s rendering of the book-within-a-book in A Tale for the Time Being; I later had a nice conversation with Ozeki about a favorite novel of mine that also has a book-within; Denise Duhamel read a narrative poem that cleverly portrayed a bickering couple observing a bickering couple from a distance, from her collection Blowout; Hilton Als, with a personal essay about Malcolm X and his mother, from White Girls; Rebecca Solnit read a passage from The Faraway Nearby about a basket of fragrant apricots; Amy Wilentz’s evocation of a chaotic street scene in Haiti from Farewell, Fred Voodo; Scott Anderson with T.E. Lawrence’s surprising refusal of a knighthood from the British monarch; Leo Damrosch’s bawdy portrait Jonathan Swift in His Life and His World; Sheri Fink’s shocking chronicle of doctors and nurses in Katrina-stricken New Orleans resorting to euthanasia in Five Days at Memorial; George Packer’s grim rendering of societal decline, typified by a Rust-belt denizen in The Unwinding; and Lawrence Wright’s chilling account of brow-beating and mistreatment among scientologists in Going Clear.

As I try to do every March when the calendar comes round to the annual awards week of the National Book Critics Circle, I attended last night’s program of readings given by many of the nominated finalists. To the left is the evening’s program. Highlights were numerous, including Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s humorous narrator’s observations about blogging, of all things, from her novel, Americanah; Alice McDermott, with a carefully paced reading from Someone; Ruth Ozeki’s rendering of the book-within-a-book in A Tale for the Time Being; I later had a nice conversation with Ozeki about a favorite novel of mine that also has a book-within; Denise Duhamel read a narrative poem that cleverly portrayed a bickering couple observing a bickering couple from a distance, from her collection Blowout; Hilton Als, with a personal essay about Malcolm X and his mother, from White Girls; Rebecca Solnit read a passage from The Faraway Nearby about a basket of fragrant apricots; Amy Wilentz’s evocation of a chaotic street scene in Haiti from Farewell, Fred Voodo; Scott Anderson with T.E. Lawrence’s surprising refusal of a knighthood from the British monarch; Leo Damrosch’s bawdy portrait Jonathan Swift in His Life and His World; Sheri Fink’s shocking chronicle of doctors and nurses in Katrina-stricken New Orleans resorting to euthanasia in Five Days at Memorial; George Packer’s grim rendering of societal decline, typified by a Rust-belt denizen in The Unwinding; and Lawrence Wright’s chilling account of brow-beating and mistreatment among scientologists in Going Clear.

All day today, NBCC board members will be making their final selections from the shortlists. I look forward to going back tonight to The New School auditorium in Greenwich Village for the ceremony, and for the festive reception that follows. The NBCC is a great organization of dedicated readers and writers. You can follow them on Twitter, @BookCritics, and check them out on the web, NBCC. Writing students at The New School interview each of the finalists, so you can also look for those videotaped conversations on the NBCC site. If you live in New York City, I recommend you attend the readings and/or the awards night, for these are two of the best literary nights of the year. Both events are free of charge, with only the fund-raiser/reception having an admission fee. If you want to support the work of the NBCC and their awards–the only book prizes given by full-time critics and reviewers–you can sign up to become an associate, non-voting member. I renew my membership each year. Here are the best pictures I took from my seat last night.